APOP100:

Introduction To Applied Positive Psychology

Week 1: Introduction

Some friends and I were enjoying dinner, where I mentioned that I'd recently begun a class in Applied Positive Psychology.

"Oh really? What's that?" a friend asked. I explained that it's broader than simply the science of being happy, but that it's an empirically-based effort to expand psychology to include not just what's wrong, but to study and understand everything that's right. 'Business-as-usual' psychology as we might understand it, focuses on the treatment and relief of misery, the pathology of mental illness. Positive psychology concentrates on what makes individuals thrive and contribute to social advancement. (Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. 2000).

My friend began to probe. "Sounds fascinating, isn't it just common sense?" A great question, and I continued that positive psychology is the classification of subjective well-being based on long-term empirical studies that deliberately go beyond such conventional wisdom. It offers perspective on evolution, positive personal traits, mental and physical health, fostering excellence, vitality, neuroscience, enjoyment versus pleasure, collective well-being, and authenticity. (Peterson, C., 2006).

It studies individual positive subjective experiences such as pleasure, gratification and fulfillment, and seeks to classify positive traits such as strengths of character, talents and what we really value as humans. But it has larger goals in understanding how such characteristics build stronger social communities and has expanded its efforts to understand national subjective well-being.

"But isn't happiness just the absence of unhappiness?" I asked my friend to imagine that they'd been granted the ability to become a superhero, but that they had to choose which color cape they wanted. If they chose a red cape, they'd be able to eliminate all the negativity in the world, such as hunger, violence, misery or injustice. Whereas if they chose a green cape, they'd have the power to grow all the good things in life, like love, optimism, kindness or gratitude. Which type of superhero would they be?

They paused. "If we get rid of all the bad stuff, then won't good naturally come as a result?" There's no truly 'right' answer. It's a thought experiment designed towards a better understanding of what it means to flourish in life. Positive psychology helps us understand that in order to truly thrive, you need to have a reversible cape, but that you can't thrive without a green cape. It's important to invest, cultivate and nurture what's right, and happiness is much more than the absence of misery. (Pawelski, MOOC, 2017)

Pressing the point, my friend replied "If I took something like this to my boss, he'd just tell me to get back to work" I continued that while a lot of positive psychology focuses on building fortitude and resilience in the individual, the economic benefits are powerful too. Increasing subjective well-being leads to better health and longevity (happy people live longer and get sick less), stronger social relationships (increased charity and better citizenship), and improved productivity at work. This in turn leads to improved customer loyalty, lower turnover, and stronger financial performance. Over time, it is ultimately proven that worker satisfaction leads to a more frequent rise in stock price. (Diener, The New Science of Happiness, 2013)

"Amazing. What can I do to help?" And now the whole table was listening.

Week 2: PERMA Profiling

Building upon the theory of authentic happiness, Dr. Martin Seligman augmented his original foundation of positive psychology to include measures of success and mastery. Predicated upon a psychology of life satisfaction as measured by positive emotion, engagement and meaning, Seligman determined that authentic happiness, as an effort to dissolve the monism of happiness into more workable terms, determined that while we often choose what makes us feel good, it’s equally important to understand that our choices are often not made exclusively for the sake of how we feel, and that there are important criteria we choose simply for their own sake (Seligman., 2012).

While the original goal of positive psychology was concerned with increasing life satisfaction, there emerged a need to focus on subjective well-being, the goal of which is to go beyond the one-dimensional measures of happiness and increase human flourishing. Seligman identified three inadequacies in his original approach. That dominant connotations of happiness are inextricably bound up with the hedonics of cheerfulness, that life satisfaction holds too privileged a place in the measurement of happiness, and that the original criteria of positive emotion, engagement and meaning, while remaining foundational, do not exhaust the elements of positivity which people choose for their own sake.

Happiness is a singular element, and well-being a construct, consisting of five essential elements distilled into the PERMA framework – positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment. Some of these aspects are measured subjectively, but others objectively, with well-being theory plural in method as well as substance. Each element must contribute to well-being, be pursued for its own sake and not merely as a path to any of the other elements. It must be able to be defined and measured independently of the other elements.

Informed by Seligman’s original PERMA construct, Diener, Seligman, Choi & Oishi conducted a study of the personal and societal attributes of the world’s happiest people, drawing differences across nations between the happiest and unhappiest among us. While the very happy were in better physical shape, had more free time, had many of their basic material needs met, had stronger citizenship and were more likely to report that they’d learned something new on the previous day, the unhappiest cohort reported much lower levels of feeling rested, significantly higher levels of stress, coupled with psychological and physical fatigue (Diener, Seligman, Choi & Oishi, 2018).

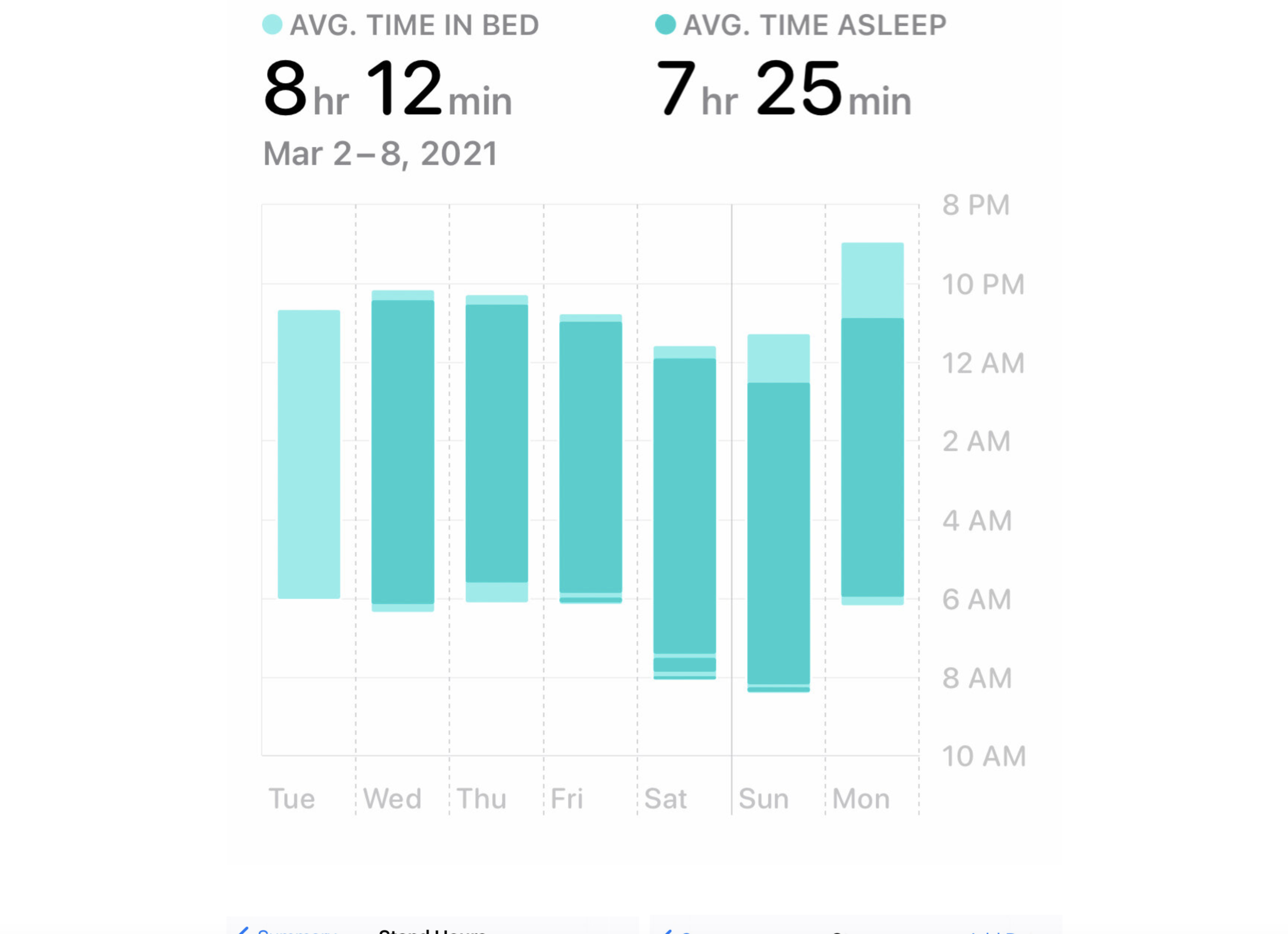

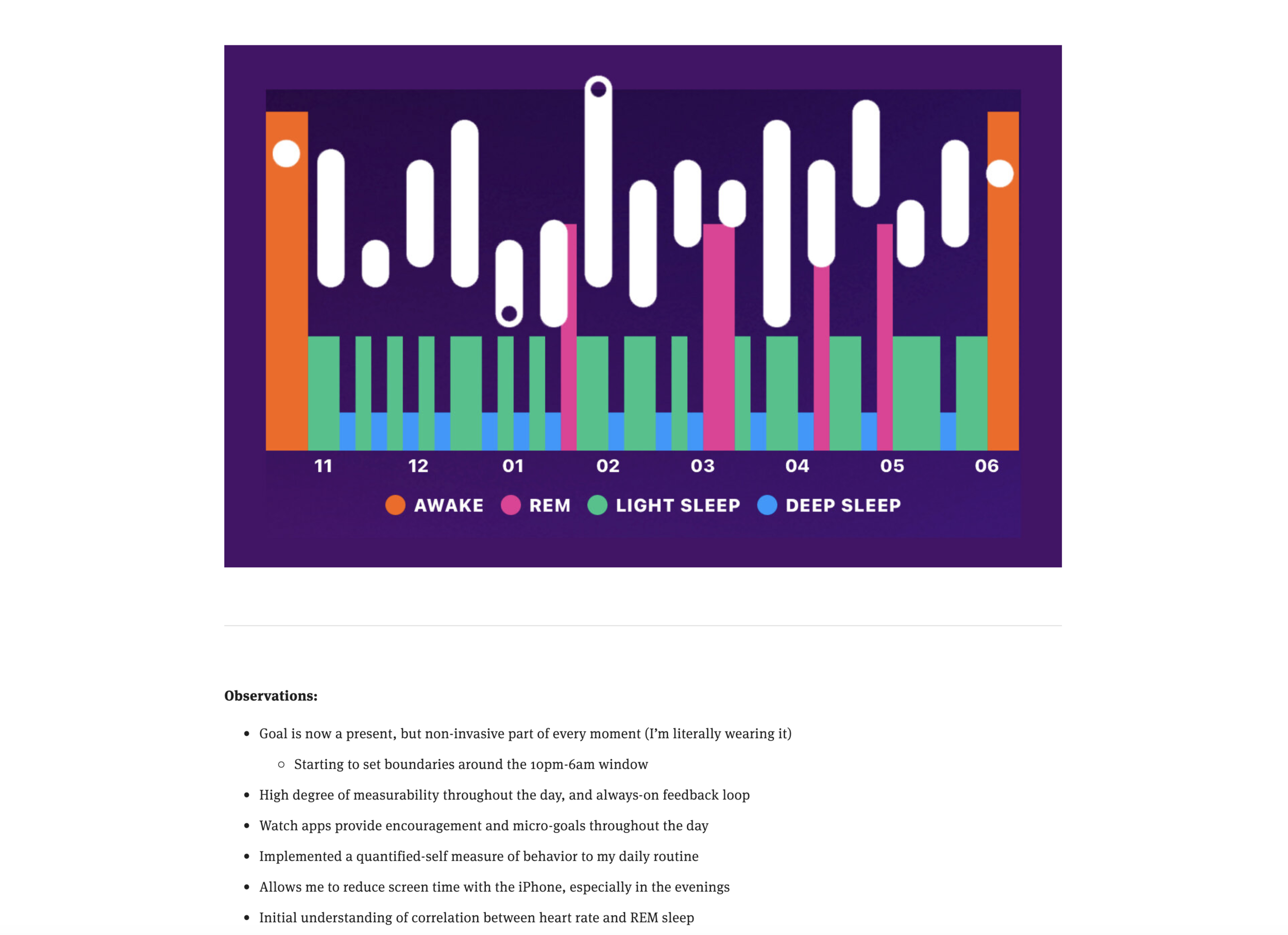

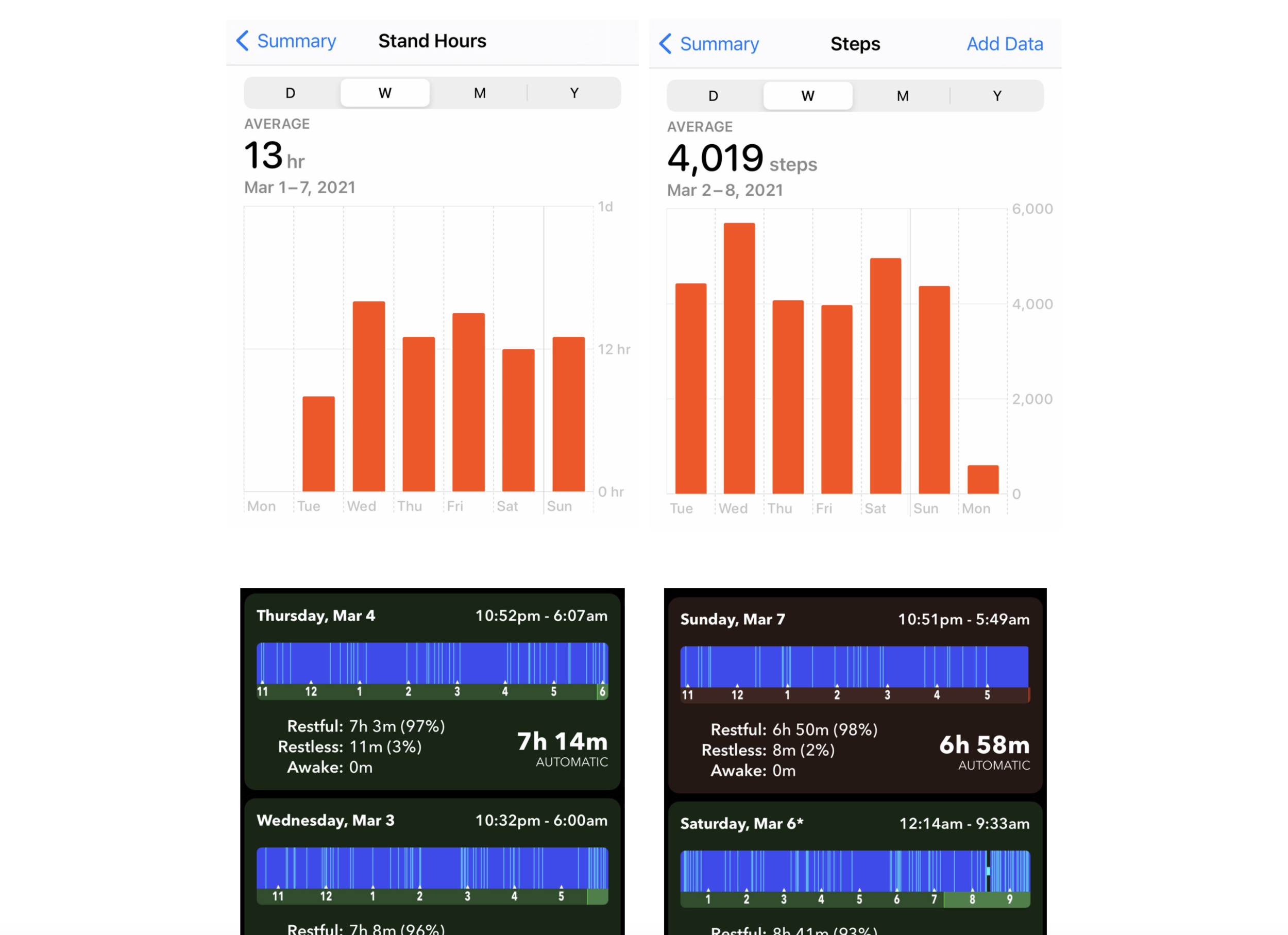

Focusing on improving the unhappiest cohort, I believe that Seligman’s PERMA construct does not include the importance of physical vitality's contribution to psychological well-being, which is often pursued for its own sake (exercise, relaxation, healthy eating and others), and can be quantitatively defined independently of the others. Explicitly the element of calm (the peace of downtime or relaxing on the beach), and especially ‘restedness’ as an active contributor to reductions in stress and health problems. Calm as a deliberate activity reduces physical and mental pain, increases overall well-being, psychological resource, learning and ultimately happiness. While strong social relationships contribute to many other aspects of overall well-being, calm is a primarily solitary, internal endeavor, and begins to deliberately break from some of the other elements' reliance upon interactions with others.

Week 3: Positive Emotions

When exploring the value of positivity in subjective well-being, it’s important to delineate the differences between positive experiences and positive emotions.

Both contribute to feelings of living life to the fullest, as characterized by happiness, euphoria, success or pleasure. But the role of positivity in subjective well-being is a broader field than simple hedonism. Positive emotions contribute to a broadened scope of attention, cognition and action, as well as building resilience around our physical, intellectual and social resources. (Fredrickson, 2004).

As one of the most prevalent positive experiences, pleasure includes a wide range of highly subjective psychological states. It is often brief, and tied to specific bodily stimulation. It ranges from the raw sensory experiences of smell or touch, through to more nuanced mental pleasures occasioned by the end of a suspenseful movie, and ultimately to higher pleasures of accomplishment (Peterson, 2006).

Pleasure can be intense and aroused, or mellow and quiet, but is multidimensional in nature. It is both an experiential quality and an experiential quantity. People can experience both positive and negative feelings simultaneously, and sometimes the interplay between the positive and negative produces higher order experiences such as the thrilling end to a sporting event (Peterson, 2006).

Conversely, positive emotions are more complex and prolonged than individual experiences, and more likely to occur in the absence of an external physical trigger. They display more subtle characteristics of physiological arousal, and are clearer markers of optimal well-being. They have the capacity to promote new and creative acts, and help to build physical, intellectual and social fortitude. These resources can later be called upon to more effectively help with adverse or challenging situations. So while pleasure is inherently an experience in the present, positive emotions have the larger payoff of broadening our thinking and strengthening our likelihood to feel good in the future.

Positive emotions also have the capacity to undo lingering negative emotions, fueling psychological resilience and facilitating the body’s ability to recover from anxiety and negative affect (Fredrickson, 2004). More resilient, optimistic and energetic individuals recover from stressful experiences faster and more efficiently. They are found to use more curiosity, humor, creativity and relaxation to confront adversity in their lives.

Love as a positive emotion is also often viewed as fleeting. However, Barbara Fredrickson’s theory of positivity resonance goes further in proposing that positive emotions don’t just signal optimal functioning, they also produce it (Fredrickson, 2020). That a single moment of genuine connection between people synchronizes our heart rhythms, biochemistries and neural networks. These micro-moments of love and connection between individuals are not just optional, but biological imperatives. They give us life, and can last all day.

Positive emotions such as pleasure and love serve to give us and others life, but also fuel our collective ability to flourish. They seed greater subjective well-being, build stronger psychological and physical resources, broaden attention and creativity, undo negative emotions, and make us and others more equipped to deal with adversity in the future. They are the nutrients of what makes life truly possible.

Week 4: Engagement

Flow is an experiential state people feel when they're doing something challenging, where they feel they have the necessary skills that if they do something right, they will be able to reach their goal (Dr. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi)

Flow dimensions include:

Balance between the skills of an individual and the activity’s demands

Merging of action and awareness

Clear goals

Immediate and unambiguous feedback

Concentration on the task

Perceived control over the activity

Loss of self-reflection

Distorted perception of time

Intrinsic motivation toward an activity (autotelic)

Conditions for flow:

Very important to be able to concentrate without interruption

Also helps if you are genuinely interested in the activity, if it's something that's important to you

Important if the activity gives you feedback, if you get immediate feedback that continues to help you be engaged

Feedback allows you to correct course and continue to be engaged

Importance of the ratio between how challenging the activity is and how much skill we have for that activity

If you play against someone at your level or just a little bit better, you're more likely to experience flow

If you play below your level you get bored, above your level you get anxious

Aftermath of flow is invigorating

Chosen Flow activity:

One way to trigger flow is to challenge our existing skills and focus on the present moment

Csikszentmihalyi characterizes it as a series of small proximal goal accomplishments

Flow totally integrates the self

At the same time expands or differentiates the self as progress in our competence towards the next proximal goal

Full playthrough God of War video game

Mix of action, puzzle solving, story, progression, character evolution

Solitary activity I'm interested in but have never done before

Builds upon previous examples of losing myself in a game filled with complex mechanics and puzzle solving

Promotes concentration, immersion, loss of time perception, loss of self-awareness, promotes different mental phenomena

Play adjusts to a level of challenge just a little above where I am on a regular basis

Play provides feedback on how to course correct

Optimal balance between skill and challenge

Game 1 (1.24.2021, Evening): 133 minutes

Early game mechanics and inventory management learning (shallow curve)

Focused on initial story progression, character introductions, world orientation

Low-level challenge

Game 2 (1.28.2021, Evening): 114 minutes

Felt tired afterwards

Very aware of it getting late and having to get up for work

Self-aware of the exercise as an impediment to the conditions of flow

Game 3 (1.29.2021, Evening): 104 minutes)

Considered first 3 games as baseline

Played for shorter time, decided to make adjustments afterwards

Puzzles in-game beginning to become more challenging

Mechanics of progression getting more complicated

Temptation to look up answers instead of rising to the challenge

How does it feel to be in flow? (7 universal conditions irrespective of culture etc.)

Completely involved in what we are doing - focused, concentrated

A sense of ecstasy - of being outside everyday reality

Greater inner clarity - knowing what needs to be done, and how well we are doing

Knowing that the activity is doable - that our skills are adequate to the task

A sense of serenity - no worries about oneself, and a feeling of growing beyond the boundaries of the ego

Timelessness - thoroughly focused on the present, hours seem to pass by in minutes

Intrinsic motivation - whatever produces flow becomes its own reward

Rooted in a desire to understand the behaviors of autotelic individuals, flow is an experiential state of absorption that accompanies highly engaging activities. It’s where we experience working at full capacity and become totally consumed with a task, to the point of losing track of time and ourselves (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002).

Flow appears most common among voluntary, solitary, self-selected enjoyable pursuits, and its propensity increases when there is an optimal balance between skill and challenge (Peterson, 2006).

But simply balancing these two fragile dynamics is not enough. Skill stretching is inherent in the concept of flow, and our attentional capacities must constantly adjust to the environment in order to stay in flow. If the challenges get too steep, then we become anxious. If our skills exceed the challenges, we become bored or relaxed (Csikszentmihalyi, 2004).

When we are in flow, we are operating at full capacity, and completely immersed in what we are doing. We enjoy a strong sense of concentration, ecstasy and timelessness, as well as greater inner clarity, serenity, and feelings that our skills are adequate to the current task.

There are several conditions that actively foster flow. We must be able to concentrate without interruption, the activity must be something that’s inherently meaningful to us, and it must give us feedback. Critically, the ratio between how challenging the activity is and how much skill we have for it allows us to understand where we need to course correct, but also fosters the desire to re-enter flow in the future (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002).

Attention therefore plays a central role in entering and staying in flow, and where we choose to direct it shapes our consciousness. An intense degree of concentration means our attention is focused in the present, to the extent that we no longer have resources available to monitor anything else. Action and awareness merge during flow and absorb our capacity for spare focus elsewhere. We don’t feel hungry or tired, time becomes distorted, we don’t think about our relationships, and we don’t consciously feel positive emotions. Our body and identity disappear.

Only in retrospect do we understand flow as intrinsically enjoyable and invigorating, but that sense of pleasure is not immediately present during the activity itself.

Through experiencing flow, we are also building psychological capital, which we can later deploy to positive effect, and the more of these experiences we have, the more likely we are to enjoy subjective well-being and happiness (Peterson, 2006). Indeed, a good life is one that is characterized by complete absorption in what we do.

As a child I loved to draw, and my earliest experiences of flow were to lose myself to creative pursuits for many hours. As a teen I loved to read, and while I’d still lose myself in a book, I’d consciously try to stretch my ability to read by increasing the challenge of each choice.

In recent years, I’ve become more aware of attention as a commodity, and the work of those who seek to aggressively attract, control and direct it. We live in an attention economy, and the amorality of ‘junk’ flow (Peterson, 2006), especially in the abuse of social media for personal, political and commercial gain is unfortunately all too present.

Week 5: Relationships

Dr. Margarita Tarragona:

Flow is not a static phenomenon

Constantly have to adjust skill and challenge in order to continue to have flow experiences

Map different emotions based on the ratio between skill and challenge

When we are having flow experiences our emotional state is neutral

(not especially happy, not focused on how we're feeling)

Game 4 (1.30.2021, Morning): 18 minutes

False start, got interrupted

Moved to noise-cancelling headphones

Game 5 (1.30.2021, Morning): 308 minutes

Saturday morning: Completely lost myself in the game

During flow, time passes quickly for the engaged individual

Attention is focused on the activity itself

The sense of self as a social actor is lost

The aftermath of flow experience is invigorating

Flow in the moment is non-emotional and arguably non-conscious

Flow as highly and intrinsically enjoyable

Adjusted environmental conditions

Headphones

Semi-darkened room

Clear calendar

Ate (breakfast) about an hour beforehand

Removed all clocks

Increased temperature in the room

Started at 9am, played through to 2pm

Usually strict adherence to lunch at noon, just completely lost track of time

Did not feel hungry until immediately afterwards

I'm on 'auto-pilot' in the later challenges (fights and puzzles)

Expected to feel tired after 5 hours of gaming

Felt motivated to bring in a huge pile of firewood afterwards

Strong sense of excitement in high challenge paired with skill puzzles and encounters

Game 6 (1.31.2021, Morning): 163 minutes

Strong signals of nearing game’s end

Momentum increases, puzzles less frequent, fights and story increase in intensity

Excitement and flow gives way to increased sense of high skill, control and relaxation

Game 7 (1.31.2021, Morning): 34 minutes

Completed the game and felt a strong sense of accomplishment

Total game time to completion: 14 hours

Felt positive emotion and vitality

High quality connections are short-term, dyadic, positive interactions, primarily associated with driving healthier individual and organizational outcomes (Stephens, Heaphy and Dutton, 2011). They are characterized as the dynamic, living tissue of mutually aware human interactions (Berscheid & Lopes, 1997 in Stephens, Heaphy and Dutton, 2011), and can be positively experienced in the emotional lift we feel when someone genuinely asks how we’re doing. Cumulatively built, they are often focused on the micro-moments of how we strengthen relationships over time.

To understand them, we assume that humans are intrinsically social and have a need to belong. Also that connections change over time, vary in quality, and are key to understanding how work gets accomplished.

Connection quality is understood by three subjective features. That those engaged in high quality connections are more likely to feel a heightened sense of positivity, and that being regarded positively builds feelings of love, respect and care. The connection’s quality is observed by the subjective experience of how mutually felt it is.

It is also understood by three structural features. That higher quality connections display higher degrees of emotion between individuals, that they allow us to bounce back from adversity, and that they foster openness to new ideas and influence.

High quality connections are strongly associated with positive outcomes, and improve individual resilience by building cognitive, physiological and behavioral resources. Even the briefest of interactions with others, particularly at work can have positive effects upon our cardiovascular, neuroendocrine and immune systems. Importantly for organizations, they help employees’ rate of recovery from illness (Lilius, Worline, Maitlis, Kanov, Dutton, & Frost, 2008 in Stephens, Heaphy and Dutton, 2011).

The cognitive, emotional, behavioral and organizational mechanisms that foster quality connections provide basic psychological pathways for us to understand and build stronger connections.

An individual’s cognitions are foundational for forming higher quality connections, especially the capacity to distinguish between our own behavior, and the perspectives of others. Emotions strongly influence how we form connections, and range from positive emotions to empathy. Importantly, the extent to which an individual unwittingly or deliberately influences the emotions of a group is a powerful connection mechanism (Schoenewolf, 1990 in Stephens, Heaphy and Dutton, 2011). Everyday behaviors, such as expressing gratitude and affirmation also play a key role in adjusting our response patterns with others. More specifically, organizations employing Agile methodology into their work processes, such as a daily standups, provide the necessary time and space in the day to allow co-workers to positively express their needs, gratitude and respect for each other on a regular basis.

John Gottman’s research into the science of long-term loving relationships finds that the overall balance of positive to negative emotions is the key index in predicting the future course of our relationships with others (Gottman, 2018). Specifically, that there is a 5:1 ratio of positive to negative interactions within stable couples, and that happy marriages have consistently strong positive attractors that allow the couples to build stronger trust, commitment and calm between each other, and effectively weather adversity.

James Pawelski and Suzann Pileggi Pawelski’s research focuses on finding and feeding the good in our relationships, in effect driving Gottman’s 5x ratio of positive sentiment (Kaufman, 2018). And even within the negative interactions, using them as an opportunity to grow even more together.

Week 6: Meaning

Psychologist Michael Steger defines meaning as an intricate web of connections, understandings and interpretations that help us comprehend our experience, and formulate plans that direct our energies towards achieving a desired future. It provides us with a life that matters, makes sense, and an understanding that we are more than the sum of our moments (Steger, 2012, quoted in King, 2014).

We consult three types of judgment in determining how meaningful our lives are (Steger 2018). We consider our lives meaningful when we have a strong sense of purpose (we’re striving for something big), we feel that they make sense (we understand our experience and identity), and that they are intrinsically worthwhile (we matter and can make a difference).

Meaning emerges from our connections with others, our interpretations of the world, our aspirations, and our evaluations of what’s around us. They direct our efforts toward desired outcomes, and provide a sense that our lives make material contribution (Steger, 2018). Those who experience most meaning in their lives often think beyond the immediate moment, and associate the greatest sources of meaning in their lives to self-transcendent activities such as harmony, spirituality and mindfulness. Work is frequently a source of meaning and a conduit to achieving important things in our lives, often infused with energy, dedication, commitment and positive outcomes (Steger, 2018).

Meaning ranks over and above factors such as depression, neurosis or income, and lack of meaning in one’s life can correlate to anxiety, stress, suicidality and many other negative life experiences. It actively predicts positive physical attributes such as better quality of life, better self-reported health, lower risk of psychological disorders, less suicidality, slower age-related cognitive decline, lower risk of heart attack and stroke, and lower risk of mortality (King 2014). Meaning is also strongly correlated with a large number of positive psychological attributes such as vitality, happiness, goal-orientation and kindness (Steger, 2013). It is absolutely a matter of life and death.

A strong source of meaning in my own life comes from my experience of surviving cancer, and the post-traumatic purpose (Frankl, quoted in Steger, 2018) I continue to feel several years later is very strong in not only taking each day as a gift, but clearly understanding that seeing everything as an opportunity to grow is what makes life rich and worthwhile. My post-cancer journey has led to exponentially stronger degrees of forgiveness, kindness, gratitude, altruism and a genuine love of learning. I am lucky to be here, and for that, I intend to make the most of every positive experience in life.

Informed by my post-treatment journey, the pursuit of individual creativity and learning is also a healthy source of meaning for me, especially during the self-isolation of our current pandemic challenges. Timothy Kasser’s work in defining ‘time affluence’ (Peterson, 2006) has resonated with me, and I’ve a tremendous sense of the opportunity of using our current challenges to build, create and invest in something meaningful. So far during the pandemic I’ve lost 60 pounds, self-published 8 books, built a habit of writing more frequently, and am pursuing a psychology degree. I am consciously using my time to thrive, and understand that life is not a rehearsal.

Week 7: Achievement

Locke and Latham’s goal-setting theory summarizes numerous aspects and understandings of the effectiveness of specific goals, from their relationship to affect and self-efficacy, to the mediators of goal effects, controlling across different countries and cultures (Locke & Latham, 2006).

It concludes that there is a positive, linear relationship between goal difficulty and task performance, and that an individual must be able to consider feedback, complexity, situational constraints and the degree to which they are intrinsically committed to the outcome in order to effectively set successful goals. Higher-level, abstract goals that adhere to these criteria lead to a mindset of greater effort and persistence, direct attention and action more effectively, and drive us to leverage our own existing abilities with a greater degree of motivation (Locke & Latham, 2006).

Intrinsic goals are central to Heidi Grant Halverson’s research into how to produce stronger outcomes, where there is a distinct difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Grant Halverson, 2015). When we pursue goals informed by relatedness, autonomy and competence (Deci & Ryan in Halverson, 2015) we increase our chances for lasting well-being and happiness, and what supercharges this effort is setting goals that are ‘difficult, but possible’.

These are goals that stretch our abilities, but challenge us to direct our brains to allocate more resources towards successful outcomes over time. As a result, our brains develop a stronger degree of realistic optimism, a belief that we’re going to succeed because we’re going to make success happen, free of the notion of a finish line of achievement (Grant Halverson, 2015). While we get better results, we also enjoy the journey of getting there a lot more, and this incremental ‘getting better’ mindset moves us from proving, to improving ourselves.

Our goals are ultimately nested in hierarchies of decision-making, with abstracted superordinate goals – those that are long-lasting and require significant investment of effort – sustaining the greatest level of stability and stubbornness in guiding our decisions over time (Duckworth, 2016).

Those who are high achieving and bring forth the greatest degree of effort in a consistent and enduring way exhibit grit, a genuine passion and purpose for long-term goals (Duckworth, 2013). Grit is sustained self-regulation in the service of superordinate goals, and Angela Duckworth’s work in researching the role of grit in achievement believes that skill is ultimately developed from effort, where we get a bigger return because it builds both skill and achievement – it makes the skill productive. As a formula, Duckworth concludes that achievement equals talent multiplied by effort squared (Duckworth, 2016).

I’ve always wanted to visit Japan, but how might I be able to put more effort towards achieving this goal in an enduring, persistent and consistent way? There are several tactical ways to do this, such as adjusting my environment or developing a superordinate fund for myself. But the most effective means are going to be becoming rigorous about what not to do in service of the goal, setting a clear timeframe for achieving the goal, implementing deliberate self-improvement tactics (learning Japanese), and moving some of the intrinsic challenges of the goal to leverage extrinsic motivation by telling others what I’m going to do.

Week 8: Vitality

Dear Team,

We’re thrilled to share five changes happening to our workplace, effective immediately. These improvements are based on proven empirical research, and we encourage you all to learn more about where these ideas have come from by using the references associated with each change.

1. Build more opportunity for us to make the right food choices. This means eating fewer refined carbohydrates such as white bread, pastries, pasta, sweets and breakfast cereals (Rath, 2016). Items on the cafeteria menu high in refined carbohydrates will be minimized, especially in the mornings. But it’s not just about removing the bad, it’s about promoting the good. Fresh fruit is now free, and hoppers of raw nuts are being installed in each department.

2. Re-engineer measurable activity back into our work lives. What we measure, improves (Rath, 2016). Every employee will be gifted a wearable fitness tracker. We will also be creating more measurable opportunities to stand, move and socialize in our work environment. It will no longer be possible to schedule meetings longer than 45 minutes, and adjustable sit-stand desks will be installed. Low-impact treadmills will be made available.

3. We will incentivize a culture of exercise. Exercise is the best medicine for our brains (Ratey, 2017). Tracked by our new wearables, each quarter the teams who have taken the most steps at work will receive a $100 Amazon gift card to gift to another team. Those teams who have surpassed an average of 10,000 steps per employee (Tanzi, quoted in Ratey, 2017) and built walking as a daily team habit (Buettner, 2009) will receive an additional $100 to give to others. So we aim to increase our steps, but we also intend to increase our gratitude to each other as a means of finding and feeding the good in our teams (Pawelski in Kaufman, 2018)

4. We will actively reduce the number of sick days through joy. It is proven that people with high positive emotion get sick less frequently, and recover from illness faster. They have stronger immune function, lower blood pressure, better stress levels, and sleep better (Pressman, 2015). At the beginning and end of every work day we will take 10 minutes as a team to share gratitude and appreciation. It is especially encouraged to participate in pairs (Fredrickson, 2017; Steindel-Rast, 2013).

5. We will change the way we determine our goals to empower our teams. Teams will now set their own individual goals in service of holistically understood business objectives. We encourage each team to develop optimistic, collaborative, time-boxed goals that the team has genuine passion for (Duckworth, 2016). Optimists are healthier than pessimists because they behave differently and do the sorts of things than make health more likely (Peterson, 2006), and this is the motivating force that drives all the other changes we’re making.

These changes are just the beginning. New ‘flow-pods’ are currently being built to replace the snack pantry for those who need to focus (Csikszentmihalyi, 2004). We’re confident these changes will result in sustained, habitual, long-lasting wellness improvements to our working hours together, and we hope they not only add more years to our lives, but also life to our years (Buettner, 2009).

With best wishes as always,

Matt