APOP290

Understanding The Science Of Positive Psychology

Week 1: How do we know… what we know?

The scientific method helps us to understand what we know about the world and each other, but it’s only ever a temporary stop on a longer journey towards confidence and certainty. Scientific enquiry is empirical, fallible, social, and predicated upon the methods of hypothesis development, methodology construction, rigorous data collection and analysis, and the public sharing of those findings (Lack & Rousseau, 2016).

It embraces the possibility for error, is not personally invested in specific outcomes, helps us to navigate confusion in a rigorous manner, and embraces the idea that we can never truly assert the truth of any conclusion. Through publication, it is deliberately self-correcting, with the belief that hypotheses that survive testing and collaborative socializing help us to build confidence in our observations, and move us more towards an understanding of truth (Lack & Rousseau, 2016).

It is less about claims, and more about momentum towards confidence that’s built upon iteration, experimentation, and successfully navigating confusion. From this we build authority.

Pseudoscience diverges from the scientific method by trading in claims of certainty. While it may appear to be built upon, and use the vocabulary of empirical research, it rarely socializes its underlying methods, lacks sufficient rigor through measurement or verifiable evidence, does not allow for self-correction, and perverts the language of science to assert a definitive conclusion. It fosters a climate of unreason, of shortcuts, and encourages us not to be questioning of its findings.

Science is concerned with building confidence, pseudoscience asserts claims.

Scientific methodology prioritizes attempts to falsify, whereas pseudoscience prioritizes attempts to verify, often through anecdotal, non-empirical methods that are compromised in the goal of presenting certainty (Lack & Rousseau, 2016). It succeeds because there is an inherent appetite for certainty, especially in uncertain times. We can be led to overstate the value of personal experience, and erode our sense of objective distance from specific claims. It encourages these personal narratives to have meaning, and leverages the power of individual anecdote (Lack & Rousseau, 2016). But its claims are rarely open to falsification, peer review or replicability. If the scientific method is transparent, then pseudoscience is opaque. These differences lead us to build confidence in dubious claims, actively invest in disinformation, and erode the authority in legitimate sources of knowledge.

So when it comes to positive psychology, how do we know if what we’re reading is trustworthy?

There is more information being produced than ever before, and for everything we find an answer to online, there are an equal or greater number of sources that tell us the opposite. Information is often sensationalized, oversimplified, and aggressive towards a culture of clicking at any cost. It games attention, is destructive, misrepresentative, and big business.

Building collective awareness to determine the trustworthiness of our sources can help us navigate the culture of unambiguous claims, and guide us towards a more balanced, empirical, objective understanding of the world. We can do this by spotting several methods inherent in how pseudoscientific claims are presented.

Anecdotal evidence and the power of the personal narrative is one of the most effective ways of building confidence and assertion around a claim. But these narratives consist largely of uncontrolled observations, have no way of establishing the truth of the claim, and do not control for known variables given their unrepresentative or small sample sizes (Lack & Rousseau, 2016). They are often claims based on unscrupulous commercial goals. Testimonials are frequently presented as truth, especially bundled with celebrity endorsement. Buyer beware.

The desire for commercial gain also leads to conflicts of interest, where a testimonial or endorsement has been traded for nepotistic, financial or otherwise exploitative ends that aren’t aligned with the welfare of the consumer (Lack & Rousseau, 2016). When considering the trustworthiness of the source, transparency around the claims is something we can look for. Where are these claims coming from? Are the claims simply cherry-picking the evidence to support their own ends? What might be the specific business relationships behind those endorsements? And what are the potential risks not being disclosed due to opaque internal conflicts of interest?

In building stronger muscles around understanding trustworthy sources, it can also be helpful to understand the specific methodologies and practices being employed behind the claims. Control groups and blind testing are standard practices in clinical trials, allow us to eliminate outlier findings, and strip the cumulative iteration and experimentation of interpretative bias and conflict of interest. Double blind tests, where neither those running the experiments nor those undergoing the tests know which group they are in, further help us to assert independence from the results (Lack & Rousseau, 2016). As such, confidence and conclusion under double blind conditions are more powerful than personal narrative, even if we may feel that they are not.

In uncertain times, the differentiation between scientific method and pseudoscience blurs, and the demarcation between the two is challenging. One prioritizes a journey towards confidence, the other towards unscrupulous assertion. One values transparency and fallibility, the other opacity and personal narrative. One leverages rigor and process, the other sensationalism, the gaming of attention and commercial gain.

Our role is to be able to tell the difference, and help others do the same.

References:

Lack, C. W. & Rousseau, J. (2016). Critical Thinking, Science, and Pseudoscience: Why We Can't Trust Our Brains. Springer Publishing Company. Retrieved from ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/upenn-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4442409.

Week 2

Identify the question this research is attempting to answer.

What is the extent to which meditation and vacation have similar effects upon affect and mindfulness in daily life?

Identify if the researchers had any predictions or expectations to the answer to their question.

Discover the relative impact of short meditation sessions practiced in a daily life that is sometimes punctuated by short vacations.

Both activities should have beneficial, incremental effects on mindfulness, and positive and negative affect.

Meditation would produce higher levels of mindfulness relative to vacation.

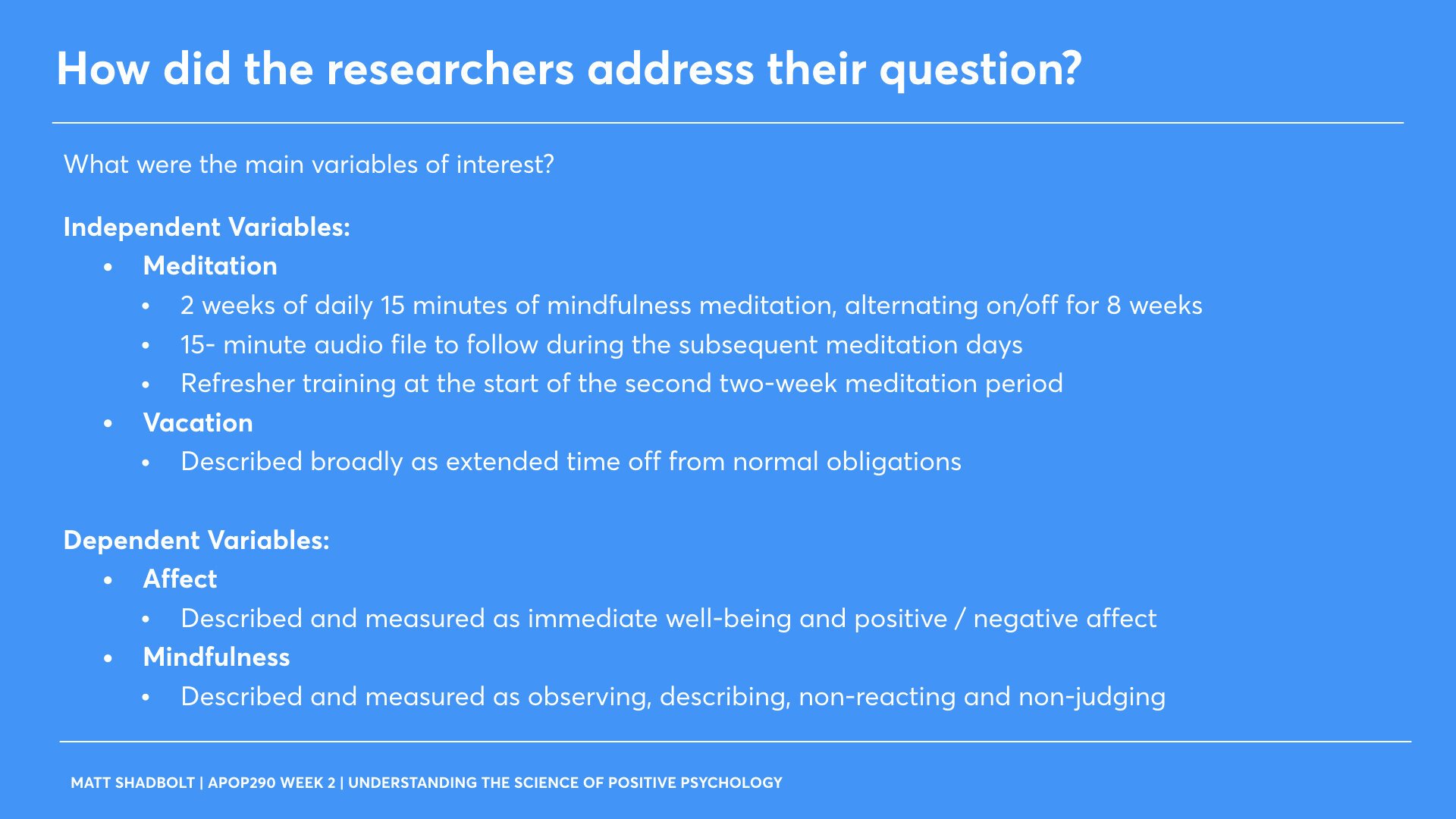

What were the main variables of interest?

Independent Variables:

Meditation

2 weeks of daily 15 minutes of mindfulness meditation, alternating on/off for 8 weeks

15- minute audio file to follow during the subsequent meditation days

Refresher training at the start of the second two-week meditation period

Vacation

Described broadly as extended time off from normal obligations

Dependent Variables:

Affect

Described and measured as immediate well-being and positive / negative affect

Mindfulness

Described and measured as observing, describing, non-reacting and non-judging

How did the researchers assess the main variables?

Independent Variable Assessment:

Participants reported on whether they meditated on a given day and which days they were on vacation.

Participants did not report on meditation environment, time of day they performed meditation, or type of vacation they took.

Participants went on vacation as they normally would if they were not enrolled in a study.

Dependent Variable Assessment:

Immediate Well-Being:

Definition: Participants were asked, ‘How are you doing right now?’

Measure: Visual analogue scale from 0 (very bad) – 100 (very good)

Positive / Negative Affect:

Definition: Participants answered questions assessing positive and negative affect in the previous 24 hours

Measure: Participants were asked how much they felt from 0 (not at all) – 100 (extremely) on several sets of emotions

Researchers averaged positive emotion responses to create positive and negative affect metrics

These were taken from the modified Differential Emotions Scale (Fredrickson, 2013; Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003) that sampled the affect circumplex (Feldman Barrett & Russell, 1998)

Mindfulness:

Two items with high factor loadings in the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (Baer et al.,2006) were drawn for each of the five facets:

Observing

Describing

Nonjudging of inner experience

Nonreacting to inner experience

Acting with awareness

Participants reported on what was generally true for them from 0 (not at all) – 100 (very much) over the previous 24 hours

Study Design:

Researchers conducted an eight-week study.

During alternating two-week periods, participants were asked to either meditate for 15-minutes per day, or not to meditate at all.

All participants received a daily survey in the evening, assessing their recent emotions and cognitions, and measuring affect and mindfulness.

Participants received mindfulness meditation training and a 15 minute audio file to follow during the subsequent meditation days.

Participants were offered a refresher training at the start of the second two-week meditation period.

13 of the 40 participants elected to attend this follow-up training.

Participants & Recruitment:

53 community citizens and psychology students filled out daily surveys of affect and mindfulness and reported when they meditated or took vacation.

Recruited first-year psychology students at a university in the Netherlands as well as from the surrounding community.

All participants were proficient in English and had not previously had a regular meditation practice.

Participant Demographics:

The average age of the 40 remaining participants was 23.7. 70% were female. 27 of the 40 participants were students.

Incentive:

Students received program credit for their participation. Community members were entered into a lottery to earn 50 euros

Participant Performance:

Four failed to complete the study.

Nine participants who finished the study meditated fewer than half of the assigned meditation days; they were excluded from the analyses.

What was the answer to their question? Although the results section will present the statistics, usually a narrative summary of the primary findings is at the beginning of the discussion section.

15-minutes of meditation has overlapping effects with a day of vacation, providing multiple pathways to boosts in well-being and mindfulness.

Meditation is the better option, as the associations of meditation with the outcome variables were outsized given that participants practiced for just 15-minutes.

The vacation effect was significantly larger than the meditation effect for momentary well-being, positive affect, and negative affect.

On meditation days, participants reported lower levels of negative affect and higher levels of wellbeing, positive affect, and the mindfulness facets of observing sensations, describing thoughts and emotions, and non-reacting to feelings.

Participants exhibited a significant meditation effect such that they reported higher wellbeing on days they meditated compared to days they neither meditated nor were on vacation.

Participants showed a significant vacation effect with higher reported well-being on vacation days relative to days they neither meditated nor were on vacation

There was not an observed additive effect of meditation on vacation

Literature comparisons:

In contrast to the findings that meditation leads to greater mindfulness relative to vacation (Epel et al., 2016), results showed similar positive associations between mindfulness and both meditation and vacation.

Leisure and vacation are not often distinguished in the literature, but should be (Dolnicar et al., 2012).

Were there any notable implications or limitations?

Limitations of the study design:

The structural dissimilarities of meditation and vacation do not invite comparisons.

There was greater variation in the number of vacation days than in the number of meditation days.

Participants were on vacation substantially fewer days than they either meditated or were not on vacation.

Mindfulness based interventions encourage participants to be open to all experiences, including negative ones

(Fennell & Segal, 2011)

In contrast to a day of vacation, a day of meditation can be cognitively and emotionally arduous

(Lindahl, Fisher, Cooper, Rosen, & Britton, 2017)

Participants were instructed to meditate on particular days but were not instructed to go on vacation (they only reported vacation days)

Did not control for expectancy effects where participants may be biased to report more salutary effects for meditation and vacation regardless of their actual impact.

Differences between meditation as a manipulated variable and vacation as a measured variable.

Relative effects may depend on the type of meditation practiced and the kind of vacation taken.

(Fredrickson et al., 2017; May et al., 2014)

Did not delineate multiple types of leisure activities, from casual to project-based to serious.

(Stebbins 2012, 2018)

Casual leisure prioritizes hedonic goals. Serious leisure prioritizes more eudaimonic, adversity-overcoming goals.

Short-term meditation practice for stress relief may have important parallels with types of casual leisure.

Sampling rate could be increased to multiple times per day, including before and after a meditation session or a particular leisure activity, to capture variable dynamics.

With both extensive meditation and extended projects, there is a higher likelihood of intermediary setbacks, or negative experiences, to be endured in service of a larger goal (Lindahl et al., 2017; Stebbins, 2012)

Limitations of the results:

The short-lived benefits of vacation fade away within weeks (De Bloom et al., 2009).

Ceasing short term mindfulness meditation practice shortly leads to declines in acquired gains

(May, Weyker, Spengel, Finkler, & Hendrix, 2014).

The results only demonstrate similarities for beginning meditators.

Results do not speak to the unique, cumulative effects of long-term meditation practice

(Lutz et al., 2004; MacLean et al., 2010), which may outweigh those of vacation.

Unable to determine how much of reported meditation or vacation effects could be attributed to a particular day’s meditation or vacation period or reflected the accumulation of effects from preceding meditation or vacation days.

Need to separate meditation from vacation periods, and include sufficient time points in both periods so that linear trends can be modeled for meditation and vacation.

Did not include between-subject control groups. A virtue of our intensive longitudinal design was that subjects served as their own controls, enabling direct within-subject comparisons of the effects of meditation and vacation

Implications for Future Research:

Examine the relative durability of the effects of meditation and vacation

Examine to what extent the results generalize to other populations, age groups, socioeconomic statuses, and nationalities.

Include an active control group which regularly listens to short health improvement lectures may help to control for expectancy effects.

Examine how longer term meditation practice may be more comparable to serious leisure.

Future Meditation Variable Research:

Investigate the relative impact of meditation to vacation in ways that facilitate disentangling acute from cumulative effects.

For the novice meditator more interested in temporary stress relief than the sorts of effects that accrue with intensive practice comparing the relative impact of meditation and vacation would be illuminating.

(Lutz, Greischar, Rawlings, Ricard, & Davidson, 2004; MacLean et al., 2010)

Future Vacation / Leisure Variable Research:

Enroll participants surrounding a period wherein they plan to take a substantial vacation.

This would facilitate more robust estimates of the relative impacts of meditation and vacation.

Not all vacations are alike. Track and categorize how participants spend their time on vacation.

Researchers defined vacations broadly as extended time off from normal obligations.

This could encompass both leisure as home-based activities and vacation as activities away from home (Dolnicar, Yanamandram, & Cliff, 2012).

The serious leisure perspective (Stebbins, 2012) may provide an interesting framework for comparing meditation and leisure.

The impact of leisure may be expected to differ between countries (ie Germany) with differing amounts of paid vacation time, based on the cultural nuances of the value and consumption patterns of vacation time.

Part 2:

Two recent online articles reporting on May, Ostafin, and Snippe’s 2020 research findings in ‘The relative impact of 15-minutes of meditation compared to a day of vacation in daily life: An exploratory analysis’ attempt to summarize and repurpose the source material, but with little accuracy or success.

Both Fit & Well’s ‘Mental health: How to feel like you're on holiday in just 15 minutes’ and Yahoo! Life’s ‘If you can't take a vacation, research says you should do this to feel less stressed’ cite The Journal of Positive Psychology as their source, both position their articles as remedial advice for lifestyle problems related to COVID-19, and both cite vague, unqualified conclusions as to the study’s actual findings, as well as editorializing their own.

Yahoo’s piece is the more credible brand source, and more accurately reports on the study’s method and conclusions, although Fit & Well’s piece is not afraid to quote liberally from the study directly in an effort to do the same. However, Fit & Well’s article is the more overtly commercial of the two, with several references to affiliate revenue relationships centered around Cyber Monday deals with Amazon. Overall, Fit & Well provides more practical, tactical advice than Yahoo, advocating for related breathing exercises, and mobile apps to download.

There are numerous misleading omissions throughout both articles. Neither article cites the authors of the study, the methods employed, the limitations of the research (for example that not all vacations are created equal, that benefits of vacation and meditation fade away within weeks, or the sustained cumulative benefits of meditation upon the results). In Yahoo’s case specifically, they lightly describe the method, but omit that the study weeks alternated between meditating and not meditating, and they incorrectly draws assumptions that all participants took vacation (‘for about 7% of the study, they were on vacation’).

Errors heavily pepper both pieces. Yahoo reports on incorrect sample size (40 instead of 53), draws conclusions that mindfulness is equivalent to less stress, confuses positive and negative affect with positive emotions, and concludes that the study offers techniques to help the reader calm down, even though the study does not report on levels of calm, or tactics for reducing anxiety.

Fit & Well’s article fares even less fit and well on accuracy. It offers advice for how to develop the same mental effect, mindset and feelings of relaxation as being on vacation, and the neurological affect of meditation. The study does not report on any of these findings. It incorrectly concludes that meditation can’t replace the benefits of taking a day off, that 15 minutes of meditation brings out the same positive associations as taking vacation, and draws false parallels between individual vacation days and general meditation practice.

So what are the strengths of each piece? Fit & Well offers suggestions for guided meditation and apps to help build mindfulness habits, they accurately (albeit liberally) quote directly from the study, and list out other activities readers can do to promote better subjective well-being. Yahoo correctly draws out the study’s conclusion that the positive benefits of meditation and vacation are only similar, has a more accurate assessment of the study’s method, and concludes that taking time off has the greater positive effect for participants.

In addition to the numerous errors throughout, Fit & Well’s weaknesses center around the multiple inline affiliate links and transparent connection to their commercial relationship with Amazon, but also the use of pseudo-scientific language and the decontextualized use of terms such as ‘vacation effect’ and ‘nonreactivity’.

Both articles offer pseudo-scientific ‘lifehack’ reporting on the original study, and are clear examples of churnalism. While Yahoo fares a little better overall, the advice drawn from the original report is vague, misleading, error-prone, commercially-driven, and motivated by the dynamics of gaming attention.

Week 5: Part One

Headspace is a self-help website and suite of mobile apps with a simple mission: to improve the health and happiness of the world. Created in 2010 as an events business, but due to increased demand for founder and former Buddhist monk Andi Puddicombe’s expert meditation and mindfulness practice, subsequently focused on its digital experiences. It boasts over 100 employees, over $100 million in annual recurring revenue, and is used by millions of users in almost 200 different countries. It leverages a freemium subscription model, whereby ten days of content are provided for free, after which users have the option to subscribe via a monthly or annual plan.

In July 2018 the company launched Headspace Health, a subsidiary that partners with the U.S. Food and Drug Adminstration to develop meditation tools that can be used as part of prescriptive programs across a range of chronic diseases. They also have commercial relationships with numerous organizations such as Amazon, Google, Nike, Spotify and Weight Watchers. The nature of these clinical, technical and commercial relationships is fully disclosed on their website. Notably, Headspace does not run advertising on any of its digital products, on or off-platform.

Headspace seeks to make meditation accessible, relevant and beneficial to as many people as possible, and the product consists of guided audio meditations, animations, articles and videos. Each session is about ten minutes long, and can be consumed individually or as part of a longer-term program. They are usually delivered by Puddicombe himself, where he often relates his personal experiences as part of the guided sessions.

Headspace’s recommendations claim to show the positive impact of mindfulness practice upon a wide range of wellbeing criteria, including stress, focus, mood, compassion, aggression, anxiety, depression, sleep, weight loss and many others. And while they are rigorous around including clear communication that their service is not intended to manage, treat or cure any medical condition, they are even more rigorous in connecting all of their content to existing research efforts. Their work has been used in a number of clinical trials investigating the effects of mindfulness training, and they have partnered with reputable institutions such as The British Heart Foundation, NYU, USC and Stanford University.

Headspace has received substantial media coverage since launch, and been positively featured on both U.S. and U.K. television, appearing on The Today Show, BBC News, ABC News, BBC science documentary Horizon, NPR and in several high profile TED Talks. In January 2021 Headspace released its first series on Netflix, with subsequent seasons being aired in April 2021 and June 2021. Online searches for the scientific evidence and positive anecdotal experiences of using Headspace return thousands of results from reliable media sources such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, NBC News, The Washington Post and others. This media coverage is comprehensively documented in the press section of their website (Headspace, 2021a)

Part Two

Headspace is currently involved in over sixty five active research studies, the majority of which are being conducted by third-party external researchers with no financial or conflicting associations to Headspace. These studies are being conducted in partnership with over thirty five scientific and educational organizations. For each published study in which they have been included, their website details the researchers, aims of the study, evidence found in the study, participants, and includes clear links to download the original research papers (Headspace, 2021b). These papers have been published in outlets such as The Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, The Journal of Business and Psychology, the Journal of Behavioral Addictions and many more authoritative scientific sources. They are not just using their app and experiences to build a business, they are also deeply invested in partnering with those doing the research into mindfulness itself.

While Headspace sees meditation simultaneously as both a practice rooted in ancient history and a topic of modern science, they are equally committed to supporting empirically researched, peer reviewed and rigorously tested studies. They have a seven person in-house science department, led by their Chief Science Officer Dr. Megan Jones Bell, who has over fourteen years of experience running National Institute of Health and European Research Council-funded clinical trials on digital health interventions. This team acts as a liaison between Headspace and the scientific community.

Headspace clearly and publicly lays out the benefits of mindfulness practice for its users, but whenever and wherever they do this, they have a consistent practice of linking to original research studies, and connecting anything that has the appearance of a false claim back to the scientific evidence (Headspace, 2021b).

For example, one talking point on their site offers that ‘Three published studies have shown Headspace can reduce stress in a variety of populations’ (Headspace, 2021b). This may initially appear as an unreliable pseudo-scientific claim of causation instead of correlation, but they support this claim by linking directly to the work of Bostock et al.’s ‘Mindfulness on-the-go: Effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being’ (2018), Economides et al.’s ‘Improvements in Stress, Affect, and Irritability Following Brief Use of a Mindfulness-based Smartphone App: A Randomized Controlled Trial’ (2018) and Yang et al.’s ‘Happier Healers: Randomized Controlled Trial of Mobile Mindfulness for Stress Management’ (2018). Similarly, when describing how 'Mindfulness has been shown to promote healthy eating behavior, and improve weight loss in overweight or obese individuals.’ (Headspace, 2021b), they consistently connect to research such as Carrière et al.’s ‘Mindfulness-based interventions for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis’ (2017). There is a clear culture of ensuring that anything they are articulating has a direct relationship with relevant, timely scientific evidence and the current thinking of the scientific community.

Given our understanding of Headspace’s internal and external dynamics and motivations, would I follow this program?

I would, and have. I have personal experience of the positive benefits of using Headspace, and have built it into an ongoing program of anxiety and depression recovery. Some of their habituation mechanics openly rely upon gamification and the importance of maintaining a streak of activity in order to reduce subscriber churn. However, I feel there isn’t just the sufficient level of anecdotal lived experience I’ve benefitted from personally, but also empirically-backed, evidence-based, peer-reviewed, authoritatively-sourced method that has gone into everything the app stands for.

In connecting my experience with a deeper understanding of their research, there is clear evidence for not only the claims made by the program, but for the specific tactics and mechanics inside each program. Each mindfulness course is carefully crafted with the original research on hand, and even included directly into many of the audio narratives from Puddicombe.

As such, this program comes highly-recommended, and given the company’s investment in research, domain expertise, their stance on supporting, but distancing themselves from commercial conflict and influence in research, and taking careful precautions to ensure that there is radical transparency in connecting their claims with the original studies, I would consider their recommendations and authority overwhelmingly trustworthy.

While the commercial considerations of their subscription model are inevitable, I believe that their relationship to, and respect of, original and rigorously designed, systematically tested research adequately weighs the risks and benefits of their business model, causes them to act responsibly and with integrity, and ultimately empowers them to positively impact millions of users’ wellbeing.

References:

Bostock, S., Crosswell, A. D., Prather, A. A., & Steptoe, A. (2018). Mindfulness on-the-go: Effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. doi:10.1037/ocp0000118

Carrière, K., Khoury, B., Günak, M. M., & Knäuper, B. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews,19(2), 164-177. doi:10.1111/obr.12623

Economides, M., Martman, J., Bell, M. J., & Sanderson, B. (2018). Improvements in Stress, Affect, and Irritability Following Brief Use of a Mindfulness-based Smartphone App: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-0905-4

Headspace (2021a). Press & Media. Headspace.com. https://www.headspace.com/press-and-media

Headspace (2021b). The Science-Backed Benefits of Meditation. Headspace.com. https://www.headspace.com/science/meditation-benefits

Yang, E., Schamber, E., Meyer, R. M., & Gold, J. I. (2018). Happier Healers: Randomized Controlled Trial of Mobile Mindfulness for Stress Management. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine,24(5), 505-513. doi:10.1089/acm.2015.0301

Week 6: Part One

How might we be able to understand not only what’s meaningful in our lives, but also develop interventions and techniques for fostering more of it, in the pursuit of increased positive well-being?

Recent scientific research has begun to assess the more granular and specific aspects of what constitutes meaning in our lives, but few studies have examined the extent to which we understand the specific nuances of meaning that are driven by individual events. And while the experience of meaning in life is closely associated with the positive aspects of subjective well-being such as improved health and positive affect, previous research studies may simply have been too broad, and may have missed much of the nuance inherent in the construct.

Research conducted at several Singapore-based academic institutions (Tov et al., 2019) seeks to address this potential gap in our knowledge. Participants from Singapore and the U.S. were surveyed on prior meaningful and meaningless events in their lives. They rated the extent to which they experienced purpose, coherence, positive and negative implications for self and others, as well as positive and negative affect. Meaningfulness here is defined not only in terms of life having a holistic sense of meaning, but follows previous academic contentions that life contains meanings that are surfaced through specific activities, quests and goals (Reker & Wong, 2012). As such, this research is not concerned with global meaning (the broader set of beliefs, goals, and frameworks that enable people to experience life as generally comprehensible and purposeful), but instead focuses on the meaning and significance of a particular event.

Within the area of specific, meaningful events, the study found it helpful to examine the existing differentiating areas of what constitutes meaningful versus meaningless. The facets that contribute to an individual’s positive implication and perception of their self include a sense of purpose, or the extent to which an event furthers the pursuit of a goal (Baumeister, 1991), their sense of the event’s significance, or the extent to which we feel our existence has importance or value (Martela & Steger, 2016), the extent to which an event had positive implications for a person’s life, the extent to which that event is connected to either the past or the future (Baumeister, Vohs, Aaker, & Garbinsky, 2013 ; Tov & Lee, 2016 ; Waytz, Hershfield, & Tamir, 2015), and finally the degree to which the event promotes positive or negative affect.

Their research found that meaningfulness and positive affect are strongly, positively correlated (r=.66, p’s ≤ .029) suggesting that as one aspect increases, so does the other. Similarly, meaningfulness and positive implications for the self are even more strongly, positively correlated (r=.72, p’s ≤ .004). Positive aspects of meaningfulness were found to be statistically significant across different experiments and groups of people, which helps us understand that these relationships are not simply happening by chance.

Conversely, meaningfulness and negative affect are weak to moderately negatively correlated (r=.22 p’s ≤ .915), which tells us there’s less signal here than positive affect. In this case as one aspect increases, the other decreases. Negative affect and meaningfulness tend to have much less influence over each other, and in contrast, negative emotions were not materially associated with meaning after considering the other facets. Even more weakly correlated (r=-.05 p’s ≤ .820) are meaningfulness and negative implications for the self. While overall comparisons between meaningful and meaningless events were statistically significant, correlations between meaningfulness and negative affect do not meet our threshold for statistical significance, likely due to the small sample size of testing, so we can’t really draw any relationship here.

Previous research (King et al. 2006, Reker & Wong, 2012, Steger et al. 2006) has provided evidence that positive affect may have a causal effect on the experience of meaning. However, the current research cautions against drawing causal interpretations around any of the facets of purpose, coherence, consistency with beliefs, implications of the event, or affective experience with meaningfulness. This research suggests that ‘when people contrast meaningful and meaningless experiences, the sense of purpose experienced in the former is notably higher than in the latter. This does not establish purpose as a cause of event meaningfulness.’ (Tov et al., 2019). So we conclude that we should resist the urge to draw causal conclusions from the current evidence, despite the strong correlations for positive behavior and mixed statistical significance for negative aspects.

Part Two

The primary takeaway from the current research is that for the groups of people measured, meaningfulness in life and positive emotions are strongly associated. Meaningful and meaningless events differed most in their levels of positive affect, purpose, and positive implications for the self, with purpose and positive affect independently predicting meaning. Measures of the extent to which the participants felt coherence in their lives generally did not predict the meaningfulness of an event.

But to what extent can we apply the results obtained from our study to other scenarios, demographics, or populations? For this we need to look at the two cohorts sampled.

Two samples were recruited for the experiment. The first sample consisted of 146 undergraduate students (100 females) from Singapore Management University, who ranged in age from 18 to 28 years old. This sample was predominantly Chinese (79.5%) with the remainder from other Asian ethnic groups.

The second sample was gathered online using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) service and initially consisted of 99 American workers. Nine were excluded from the final research for ethical violations in their responses (plagiarism). The final group consisted of 90 workers. 35 females, ranging from 21 to 63 years old, were predominantly of European American ethnicity (63.3%), but also included African American (12.2%), Asian American (12.2%) and people of other ethnicities (9%).

While we applaud the research for its diversity in design and application to non-western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic populations, both samples face challenges when trying to meaningfully extrapolate to other groups of people. The first sample suffers from non-probability convenience sampling (which means that the group of people included in the experiment mainly came from those nearby and willing to participate) and selection bias (which means the people included aren’t representative of the broader population), and only provides evidence for a very specific, localized ethnic background that comprises of disproportionate gender representation and narrow ten-year age range.

The second sample is more diverse in ethnic consistency, gender and age range, but ~40% smaller in size. Future research might be augmented by proportionate stratified random sampling (in which the proportion of respondents in each of the various subgroups matches the proportion in the population) across a significantly larger (10x the original sample) group of participants.

While the study highlights some encouraging initial signals, neither sample would be considered sufficient for broader application to other populations, and we can only use the evidence shared in the context of consideration for more substantial research. Both to offer more causal insight into the structure of meaning through larger and more diverse sampling, but also to offer broader, more diverse and applicable evidence for understanding what’s most meaningful in our lives.

References:

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Aaker, J. L., & Garbinsky, E. N. (2013). Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 505–516.

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 179–196.

Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. Journal of Positive Psychology, 11, 531–545.

Reker, G. T., & Wong, P. T. (2012). Personal meaning in life and psychosocial adaptation in the later years. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 740–779). New York: NY: Routledge.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93.

Tov, W., & Lee, H. W. (2016). A closer look at the hedonics of everyday meaning and satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 585–609.

Tov, W., Ng, W., & Kang, S. (2019). The facets of meaningful experiences: An examination of purpose and coherence in meaningful and meaningless events. The Journal of Positive Psychology. DOI: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1689426

Waytz, A., Hershfield, H. E., & Tamir, D. I. (2015). Mental simulation and meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 336–355.

Created as an article here: https://matthewshadbolt.com/go-outside

Week 7: Scientific Communication for General Audiences

Key Takeaways:

Being outside in nature for as little as five minutes can positively benefit your mood

These benefits don’t necessarily increase with time, although longer contact with nature can help decrease negative emotions

These findings might be an effective approach for reducing levels of stress, anxiety and depression in University students

Deep breaths. Fresh air. Long walks on the beach.

It’s no secret that being in nature helps us feel better. And for those of us who’ve been inside a lot more often recently during the pandemic, simply being outside with others can be an increasingly rare luxury.

But how long do we actually need to be outside in order to start feeling better? Recent research from the University of Regina in Canada has found evidence that being outside in nature for as little as five minutes can have powerful positive effects upon our well-being.

There’s already substantial scientific research that contact with the natural environment is a good thing. Not only for our physical health, but also for our emotional well-being. It not only increases our positive emotions such as gratitude, generosity, trust and co-operation, but actively reduces negative emotions such as stress, anxiety and depression. Despite all of this, and the fact that nature is readily available to most of us, almost a quarter of Canadians who experience anxiety and mood problems don’t seek help, and there’s very little research into the specific benefits of spending different lengths of time in nature.

The researchers conducted two different experiments. One that examined whether five minutes of being in nature helped people’s mood more than spending a similar time in an indoor setting. And another that looked at whether fifteen minutes of being in nature would be more beneficial than five minutes. Both studies took place during the late fall and winter months, and measured the participants’ mood before and after the activity. They were primarily female students aged around 21 from The University of Regina’s Psychology Department.

In the first experiment, those assigned to be observed indoors sat in a windowless room, whereas those assigned to be outdoors sat on a nearby park bench. The researchers took measures of their mood, and then they were asked to take a rest. Accounting for the larger proportion of women in the experiment (although overall gender wasn’t found to be a concern), they found that those who’d been outdoors showed a significant and robust increase in their positive feelings, a sense of feeling part of something meaningful in the world, feelings of interconnectedness, and awe when compared to how they felt before the exercise.

These results indicate that five minutes of being outside in a natural setting such as a park might be enough to increase one’s feelings of positive emotion. Even in this short amount of time, the researchers suggest we’ll simply feel better.

The second experiment studied whether being outside in nature for longer than five minutes made a difference to how the participants’ moods benefitted. The idea here was that if five minutes results in an increase in positive feelings, would fifteen minutes be even better? This time around, there wasn’t an unfortunate group who had to stay indoors. Both the five minute group and the fifteen minute group got to be outside, but the difference this time was that the researchers also measured aspects of negative mood such as stress, anxiety and depression more closely, to see if fifteen minutes would differ from five minutes.

In short, the researchers found that it didn’t really make a difference to feeling more positivity if you were outside for five minutes or fifteen minutes. The positive benefits of both were essentially similar, and the notion that being outside longer would continue to improve your mood the longer you did it wasn’t found to be an influence on their findings.

But there’s a few interesting differences between the experiments. Notably that in the first experiment the participants felt more positive emotion but not necessarily a decrease in negative emotion, whereas the reverse was true in the second experiment, who saw an improvement in negative emotions such as anxiety or stress. The researchers also suggest that perhaps a person’s mood before they go outside, especially for such a brief time, influences whether their experience increases an already positive mood, or decreases a negative mood.

The most obvious thing the researchers found is the ease with which nature can be used to improve our mood, and of course, almost all of us can do this. Short amounts of time outside in nature have the same benefits on our well-being as longer periods of time, and this is especially important for University students, who consistently show higher levels of anxiety, depression and stress than the general public. The researchers plan to do more experiments into understanding what makes these benefits can be long-lasting. The research here also only applies to a very specific group of people sampled (mainly female students from a Canadian university), and being able to apply it to larger, broader and more diverse sets of people is also a next step. If you’re interested in reading more about the studies and what’s next, you can find the original research paper here.

So, want to feel better but don’t have the time? Now we know that grabbing as little as five minutes outside in the park might make all the difference.

The ethical foundations of scientific communication are the most rigorous, and beneficial aspects of the field, while at the same time being flawed, prone to abuse and most open to improvement. The ethics of science communication are a contentious mine of discussion, but one that’s not necessarily evolving at the same pace as unparalleled technological advance and an increasing culture of radical information transparency. Here I discuss two existing forms of scientific communication I appreciate, the moral foundations of ethical research and the open science movement, as well as two aspects I think can be improved, replicability and peer review.

Part One

The moral principles underlying scientific research, of weighing risks against benefits, acting responsibly and with integrity, seeking justice and respecting people’s rights and dignity (Jhangiani et al., 2019) are the foundation of how the practice seeks truth, builds knowledge, self-corrects, and is respectful towards those it seeks to help. It strives to genuinely develop helpful treatments and further our understanding of what is known and understood. Through established method it mitigates against risks to society, and enforces a professional obligation to carry out research in a thorough and competent manner (Jhangiani et al., 2019). It promotes trust, fairness, privacy and actively seeks to minimize ethical conflict in order to fill in gaps in the research literature, subsequently disseminating that information to the general public. It’s a highly admirable set of principles, and forms the cornerstone of how science communication discovers and articulates its value to the world.

If science is primarily concerned with observing, collecting and analyzing evidence (Spellman et al., 2018) in order to test against hypotheses, and more people are engaged in communicating and improving science than ever before, how might we retain and enforce those core ethical principles? As research has evolved, conflicts of non-replicability, the abuse of statistical methods, lack of access to materials and data, selective interpretation of the findings, and activities as serious as fraud have the potential to erode and dilute our moral and ethical principles of research.

Open science is an active set of reforms which aims to reduce these risks by making scientific practice and communication more transparent, fallible, iterative, accountable and available for evaluation. Many researchers believe this approach to represent a return to the core beliefs of how science research should be conducted (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955; Feynman, 1974 in Spellman, 2018). It seeks to eliminate questionable research practices such as undisclosed flexibility in measures, samples or reporting, hypothesizing after the results are known, removing nonsignificant manipulations and measures from manuscripts, selective publication of results, and to systematically examine the extent and causes of failures to replicate (Spellman, 2018).

These reforms also include reducing the selective deletion of outliers in order to influence statistical relationships, the selective reporting of results, performing inferential statistical calculations to see if a result was significant and subsequently deciding to collect more data, and worst of all, the outright fabrication of data (Jhangiani et al., 2019).

With more access to information than ever before, and an unprecedented volume of information (and misinformation) being published every day, the open science movement is a determined attempt to cut through the noise, eliminate questionable practice, remedy problems created by past practices, and reinforce faith in scientific practice and communication. That’s a good thing.

Part Two

But despite our solid moral, ethical and open principles, science communication is not without significant challenges. The replication of findings is one of the defining hallmarks of science (Diener, E. & Biswas-Diener, R., 2020), as it increases our confidence that the result actually exists, and gives the general public faith in the scientific process. Psychology’s recent replicability crisis highlights researchers’ widespread inability to replicate earlier findings. And this is only compounded by a lack of generalizability in the original studies to non-WEIRD populations. For example, the Reproducibility Project (Open Science Collaboration, 2015 in Spellman, 2018) found that not only were 36% of the original studies found to replicate significant effects, the effect sizes were on average, only half of those found in the original studies. Similarly, data reported in 2015 by the Open Science Collaboration project found that only about one third of psychological studies published in premier journals actually replicate. Without replicable evidence, there is no reason to believe in scientific psychology (Diener, E. & Biswas-Diener, R., 2020).

But knowing the extent of the problem is the best path for seeking the solution. Advances in technology, acknowledgement of questionable research practices and active attempts to reduce them, and actively reforming the structural problems that underlie the replication crisis are all admirably very much in progress. Widespread adoption of these practices however, is not pervasive. Technology offers an incredible opportunity to help solve an intrinsically human problem, but of course, it’s dependent upon the humans wanting to being helped.

Any ethical consideration the human implications of scientific communication has to include the process of peer review, the process of subjecting an author’s scholarly work, research or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the field (Kelly et al., 2014). Peer review helps to determine the validity, significance and originality of the study, seeks to improve its quality, and provides suggestions for correcting errors prior to publication.

However, peer review is a slow, manual, human process that can stifle innovation, and act as a poor filter against plagiarism (Kelly et al., 2014). And while anyone can be eligible to perform the process of peer review, these activities are typically not paid, and instead seen by some scientists as an opportunity to advance their own research, build experience on a resume, and grow their network. This inevitably introduces conflicts of interest, the opportunity for bias, nepotism, and a culture of quid pro quo.

Independent of the communal mechanics of the peer review process, and despite many in the scientific community feeling that it is their academic responsibility to perform reviews, the acceptance of low quality or even fake papers is surprisingly prevalent. In a 2013 study, John Bohannon found that of the over three hundred journals his team submitted fictional papers to, more than half accepted the fake paper. And although almost one hundred journals rejected the false papers, there is evidence that predatory, financially-based editorial practices exist in scientific communication. The average acceptance rate for papers submitted to scientific journals is about 50%, with about 41% of those accepted on the condition of revision, and only 9% accepted without requests for revision (Kelly et al., 2014).

Further criticism of the peer review process suggests that there is little evidence that the process actually works as intended, that it is not effective at detecting errors, that it is predicated upon output (volume of manuscripts published) rather than outcome (dissemination of genuinely helpful interventions), the inability to accurately detect plagiarism, and that there are a limited number of people sufficiently competent to conduct rigorous peer review compared to the vast number of papers requiring review (Kelly et al., 2014).

Despite all of these criticisms, based on a recent survey by the Publishing Research Consortium, 64% of academics are satisfied with the current system of peer review. Similarly, 83% of respondents expressed support for the idea that peer review provides control in scientific communication (Kelly et al., 2014).

Establishment of a centralized set of standards, badging and a single point of peer review workflow (for example all peer reviews go through a centralized database that can be used to optimize manuscripts across the field) might be a few ways we can improve, but technology clearly has a more helpful role to play in bringing order to an already highly fragmented set of approaches. But this requires adoption, which takes time and investment.

For a scientific practice so strongly predicated upon fallibility, self-correction and null hypothesis testing, perhaps we should be applying these same moral and ethical principles to the economics, systems and publishing practices of the individuals inside of scientific communication itself. It’s time to help the humans.

References:

Diener, E. & Biswas-Diener, R. (2020). The replication crisis in psychology. In R. Biswas-Diener& E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/q4cvydeh

Jhangiani, R. S., Chiang, I. A., Cuttler, C., & Leighton, D. C. (2019). Research methods in psychology (4th ed.). Canada: KPU. https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/psychmethods4e/

Kelly, J., Sadeghieh, J., Adeli, K., (2014) Peer review in scientific publications: benefits, critiques, & a survival guide. The Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.ifcc.org/media/332102/eJIFCC2014Vol25No3pp227-243.pdf

Spellman, B., Gilbert, E., Corker, K., (2018). Open Science. Stevens' Handbook of Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience, Methodology. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.