Jan van Eyck Akademie: Year Two

Postgraduate Laureate Masters Degree

The Netherlands, 1996-1998

After completing my Bachelor’s degree in Critical Fine Art Practice at Kingston University, I chose to do my postgraduate studies in Maastricht, The Netherlands at The Jan van Eyck Akademie. I’d gotten into the Goldsmith’s and Central Saint Martin’s College postgraduate programs in London, but elected to go to Holland specifically to work with Jon Thompson, Avis Newman and Jan van Toorn. I’d traveled over on the (then new) Eurostar train for an interview, and been incredibly impressed by the facilities, environment and support the participants had access to, and genuinely felt it was a place that afforded students the time and space to do their best work.

I had been recommend to apply by a couple of my Kingston professors, who were previous students of Jon’s at Goldsmiths, and felt strongly that I’d be able to develop and experiment in a meaningful way at the van Eyck.

It’s a small institution which only took 8 participants per Fine Art, Design and Theory disciplines each year, and actively encouraged cross-functional collaboration and engagement. At Kingston I’d been making books of what I’d written, which allowed me to start learning desktop publishing and photo manipulation, but my knowledge of the process was really nascent, and very often I wasn’t doing the work myself. My goal was essentially to lock myself in the computer room, and emerge two years later with the ability to build anything I wanted, which is exactly what happened. As a result, I naturally gravitated to spending most time with the design department.

End of Studies Colloquium Presentation (1998)

This remains one of the most fun and rewarding things I’ve ever worked on. At the end of the two year study period at The Jan van Eyck Akademie, students were required to publicly present the arc of their efforts to the institution’s board of directors. Before I got to the Jan van Eyck I had never used a Mac, so I spent most of my time learning, absorbing and experimenting with what might be possible. I’d mainly focused on CD-ROM design, user experience experiments, and building small-scale websites, but during the second year I’d spent most of my time working on game design, mechanics, and large-scale environments.

When it came time for the colloquium, I took the game Myst, disassembled it from it’s original Hypercard stack, reassembled it in the object-oriented user model offered by the (much missed) Apple Media Tool, and hid all my work on the island. So when it came time to present, I simply gave the board a tour of the island. Projects were hidden in books in the library, appeared when you pulled a switch on a wall, or were hidden in clock towers, reflecting pools or instrument panels. Due to file size restraints at the time, I ran everything locally for the purposes of the presentation, but ultimately housed the project on a CD-ROM which acted as a centralized application launcher and prompted users to insert each respective disc.

This was one of the projects which contributed to my winning of the 1998 Jan van Eyck Purchases and Collections award, and my work being acquired by the institution for their permanent collection.

Virtual Environments: 3D Engine Customization (1998)

During my time at the Jan van Eyck, especially during the second year, I built a large number of virtual environments, exploring the idea of the relationship between viewer, player, design and interaction using Bungie’s Anvil and Forge software for the Marathon game engine. Taking advantage of the mandatory texture mapping, I built a full-scale virtual museum housing an Andy Warhol collection, which included numerous galleries, an outdoor sculpture garden, and even a storage basement. Included here is also the wireframe animation, which shows the extent of the overall model.

From Kindergarten to Total Carnage (Lecture, Amsterdam 1998)

From the Stichting de Geuzen website:

”From Kindergarten to Total Carnage was a presentation by artist Matthew Shadbolt . The name refers directly to the level of skill a player chooses when playing particular computer games. The simple and most basic level is ‘kindergarten’ and the most difficult is and usually results in ‘total carnage’.

With a large beam projection from the computer, Shadbolt guided the audience through some of the earliest computer games discussing the challenges of “Pong” where minimalist vertical lines engage in a bout of tennis in the black void. And from this very rudimentary stage in game development he moved to the more recent and sophisticated “Deep Blue” project, a computerized simulated chess partner that continues to challenge the greatest chess champions today. While laying out this history of gaming, he referred to classic representations of artificial intelligence in films such as the benign “R2D2” in “Star Wars” and the feminine mechanical body in “Metropolis”. He illustrated the dystopian image of technology by looking at “HAL/9000”, the rebellious computer in Stanley Kubrick’s “2001- A Space Odyssey” which rages out of control turning against its creator, man.

For Shadbolt, these cinematic archetypes reveal our hopeful expectations as well as our anxieties with regards to the development of computer technology.”

Virtual Environment Experiments: 3D Engine Customization (1997)

My first year at The Jan van Eyck had been defined by experiments resulting in CD-ROM production, but during the summer of 1997 I spent 3 months in Phoenix, Arizona where I discovered Bungie’s Forge (map editor) and Anvil (physics editor) engines, which powered their Marathon gaming platform. These tools allowed users to create their own customized environments, sprites, and game design experiments. They also unlocked the ability for me to take everything I’d been doing with CD-ROM design, and apply it to the mechanics of multi-user interaction in a live environment. My love of Bungie’s products returned much, much later in a different form.

I created a large number of multi-user network gaming environments, including several sprite-based typographic executions. These were all eventually gathered together as a series of custom designed and packaged CD-ROMs.

Lost & Found Event Video Wallpapers (1998)

On several occasions I was invited to speak in Amsterdam on the subject of my work with developing digital games, and created several live wallpaper-based videos which ran in the background during the event as attendees mingled and networked at the bar. The monthly events took place in the famous De Waag Building, best known for where Rembrandt used to paint.

One of the executions I created was a large-scale network gaming event, where players competed against each other live within a virtual representation of the building which I’d built in Forge. They not only competed against each other, but also against a number of ‘Lost’ ‘And’ and ‘Found’ opponents which also inhabited the space.

Also pictured above are a number of postcards promoting the event, designed by Mevis & van Duersen.

Quake Radius Remapping (1998)

As I deepened my experimentation with disassembling game engines and reassembling them with new and different experiences, I made several versions of Quake, notably taking the idea of applying classic game mechanics to more immersive gaming engines, and simplifying how the user played the game by taking them away from the sense of reality the original game offered. By the late nineties, games were becoming increasingly realistic, powered by better, faster 3D engines, becoming more complex in terms of narrative, and were moving away from simpler platformers, often to the detriment of actual gameplay.

I publicly presented some thoughts on this idea in the form of a talk entitled ‘From Kindergarten to Total Carnage’ at the ISEA98 conference in Liverpool, and at the Stichting de Geuzen in Amsterdam. I also shared a more comprehensive overview of the current state of game development from a design and user experience perspective for Eye Magazine entitle ‘Live. Die. Eat. Cheat.’ in the Winter 1998 issue (also included in the same issue was my review of Quakeadelica, a London-based multiplayer Quake tournament).

With a nod to how I’d eventually start thinking about product development, the notion was ‘how might we apply the gameplay and user experience from a simpler gaming era to modern games in a way which allows users to focus on the challenges, instead of the immersion?’. Quake Radius displayed a fixed, flat base of color around the user, out around them for a specified radius of space during the game. So as you moved through the environment, you could only experience it in terms of the pure, flattened gameplay in your immediate vicinity.

Random.Wad (1998)

Duke Nukem 3D Environment Design (1997)

My experiments with multiplayer level design and interactions for Duke Nukem 3D only really extended to specific physics around water and breaking glass, both of which were enhancements on the original Forge and Anvil possibilities from the Marathon engine, but the weapons loadouts contained some fun traps around filling rooms with mines, or having players leave fake doppelgängers around the level.

Many thanks to designers Peter Bilak and Jürgen X. Albrecht for helping me with all the testing.

Manic Miner Levels Re-Write (1998)

I’d been a long-time fan of the Manic Miner / Jet Set Willy franchise, ever since I played them on the original ZX Spectrum as a child, and became fascinated with the early efforts to track down legendary programmer Matthew Smith. As my understanding of game emulation, especially how to package and distribute my work on CD-ROM increased, I needed to form more discipline around file size in relation to performance. I set myself the challenge of trying to get an entire multi-level platform game on a single 1.2MB floppy disk.

Again using level-editing emulation software, I created 20 new levels for Manic Miner, aimed at an advanced level platform player. These were intended as a sequel to the original 20 levels, and distributed on single floppy disks.

Part One: Interactive CD-ROM (1997-1998)

Built using the Apple Media Tool, an interactive forerunner to Flash (without the ability to run online, this was really a way to build CD-ROMs and localized presentations), Part One was a large-scale interactive project I built during my second year at the Jan van Eyck Akademie.

The loose premise was to connect Radiohead’s Paranoid Android to a narrative around the demise of the Spice Girls, but the project led me to all manner of weird and wonderful corners of the web (here’s a good resource for what that rabbit hole looks like today), and the project ended up becoming more of a diary-like interactive document around online community, user interactions, conspiracy theories and the then emerging field of falsified media coverage. Of all the projects I worked on at the Jan van Eyck, this was the one where I experimented most heavily with user experience in terms of menu design, user journey mapping, video integration and how to tie an overall narrative to a more holistic set of identity work.

CD-ROMs (1997-1998)

Anna (with Marion Delhees, 1998)

By the end of my second year at the Jan van Eyck, I was helping other designers code and build their own interactive projects, the collaboration around which I found new, and really inspiring. Most of my work up until then had really been a solo affair. Being able to work with another designer in creating something together, in this case an interactive, virtual human, was something that I still find incredibly rewarding today. A colleague of mine at the Jan van Eyck, and now running her own highly successful design shop, Marion was one of the first of many collaborations I’ve been lucky enough to be a part of.

Mapping The Concrete Point: Exhibition & Collaboration (1998)

One of the great cross-functional benefits of working at the Jan van Eyck Akademie was the opportunity to collaborate with participants from other disciplines on public projects. Created in partnership with Dutch sculptor Gerard van den Berg, our ‘Mapping The Concrete Point’ exhibition in the exhibition space of the Jan van Eyck housed collaborative works in both sculpture and painting (mine are the ‘Close’ and ‘Find’ wall paintings).

Emulation Edition (1998)

Created for the final Jan van Eyck Akademie Open Days exhibition, Emulation Edition consisted of 12 multiplayer gaming levels, stripped of all realism and reduced down to their core constituent parts, and represented the culmination of all the game design I had worked on during my second year. My end of year show was supported by Apple Benelux and Bungie.

This was one of the projects which contributed to my winning of the 1998 Jan van Eyck Purchases and Collections award, and my work being acquired by the institution for their permanent collection.

While almost all my work over the past two years had been housed inside the computer, for the purposes of the public exhibition, I assembled a gaming environment consisting of a closed network of 3 computers, and allowed visitors to play against each other across a number of different levels.

Enjoying the game here is Dutch writer, activist and curator Ine Gevers.

Tekken Unpacking Experiment (1998)

This project isn’t something I worked on during my time at the Jan van Eyck, but was developed in that weird space of time after I’d returned to London but was looking for a job. I’d always loved the Tekken series, and wanted to experiment with game emulation software for the Playstation, but disassembling some of the source code as I’d done with the Emulator project, and running it through a Mac. The results were often chaotic, but always beautiful, and I wish I’d be able to work on this for longer than I actually did.

X-Men Unpacking Experiment (1998)

The X-Men project was a sister project to the Tekken disassembling project above, taking an existing Playstation game, ripping it apart, reframing how the graphics worked without affecting the gameplay, and then recompiling everything and running it through a Mac emulator to see what would happen. Again, the results were chaotic, gaudy, and always interesting.

Pac-Man 2000 (1998)

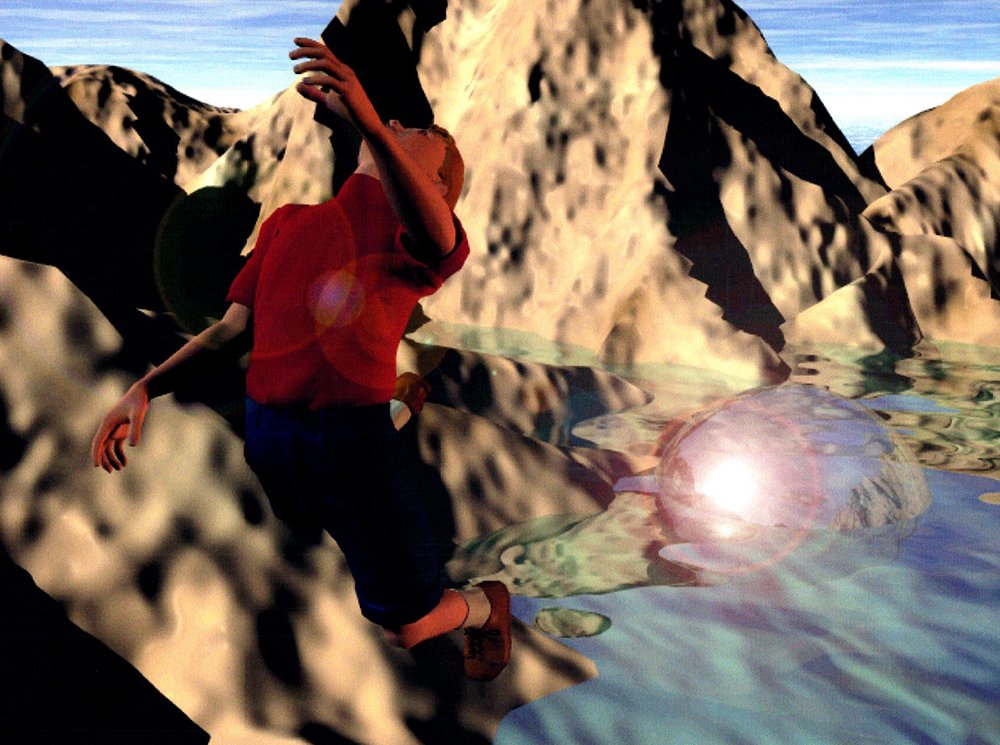

In parallel with my virtual environment experiments, I also learned how to build and animate 3D models, characters and environments from scratch. Mainly built off Strata Studio Pro, Bryce and other off-the-shelf software such as Adobe After Effects, I created an animated sequence of hypothetical video game characters for a futuristic version of Pac Man. This project was featured in the October 1998 issue of MacWorld magazine, and bundled with the free cover CD-ROM.

3D Rendering Experiments

These experiments, created in Bryce, Poser and Adobe After Effects, were mainly exercises in learning to how composite and render different layers of animation from different pieces of software in a way that appeared seamless and believable. I was working on these at the very end of my tenure at the Jan van Eyck, and while the work continued to some extent when I returned to London, I mainly just used the still outputs to create a number of freelance flyers and postcards for various nightclubs around the city.

“Before coming to the Jan van Eyck Akademie Matthew Shadbolt had worked fairly extensively on both sides of the divide between theory and practice. His practical work too covered a number of different areas from sculpture and object-making to different kind of image-making involving photography and computer processing. By contrast his time in Maastricht has tended to be dominated by work with the computer and this he has developed to a high degree of sophistication.

The main body of his work - which takes the form of a beautifully packaged series of CD-ROMs - plays with the format of the computer game. His interest, of course, reaches far beyond the format itself, indeed, it is simply the vehicle through which he explores - in a thoroughly speculative way - the virtual space played back from the computer screen. As a corollary to this ‘virtual play’ he has also become more fascinated with interactivity, and his work shows a gathering complexity of possible forms of interaction using multiple screens picturing the same virtual geography as the site of play.

It is more appropriate to define Matthew’s time at the Jan van Eyck Akademie as part of a journey rather than a series of objectives achieved; although, along the way, there are discreet achievements in abundance. But the overall sense of his work is that of one highly speculative project the terminal point of which is only ever a temporary stop, a provisional objective achieved. There is no doubt that Matthew Shadbolt has done important work during his time at the Jan van Eyck Akademie and that he will continue to break new ground with his work in the future.”

Jon Thompson, Armand Mevis, Avis Newman, Dawn Barrett

Department Faculty Leadership, Jan van Eyck Akademie