Piero Manzoni

Lecture transcript, 1995

This seminar is fairly condensed, compressed into copies of the abstract which I've handed out. If you refer to that it may be a little easier to follow where I'm going here. Manzoni's work can certainly be described as following within the parameters of some sort of pseudo - Duchampian legacy, and as well as giving some form of overview to Manzoni's somewhat brief artistic career, this seminar will try to situate Manzoni in terms of being a precursor of subsequent conceptualism, and also in terms of what we actually mean by 'traditional artmaking', so here goes.

Amongst other things, Manzoni's work, which was produced over a relatively short time in the context of the mid fifties until the early sixties, (notably at the height of artistic mythmaking according to American Greenbergian criticism) tries to come to terms with many of the stereotypes which appear to inhabit what we now know as 'artistic practice'. This dictionary definition seems to suggest that 'traditional' accounts for nothing more than a method which has been continually used and re-used, presumably over a long period of time. However, I would argue that Manzoni's 'critique' (as well as his continual 'interrogation' of the role of the artist and the artwork and a parody of their supposed excessiveness) tends to deal with 'traditional' in terms of the 'fundamental'. What are the basic fundamentals of artistic practice? Surely this must include such elements as authorship, line, colour, form, discourse and dozens of equally important others. Perhaps one 'aim' is to question a fundamental to such an extent that it itself creates a new fundamental, as in the case of Duchamp.

Coupled with this kind of quasi-modernist critique of the practice itself, is the premise, paradoxically, that his work should, in some sense, obstruct an artistically 'critical' response, for example one which was based upon taste and 'expression', substituting it with a more basic and universal form of 'response'. In doing this he chose to focus upon the relationship between three major art basics, the author, the work and the spectator.Therefore the underlying theme of his work can be seen to be an attempt to somehow remove art from its elitest enclave, and bring it into a wider, perhaps more public domain. The majority of his output consisted of his relatively unknown 'Achromes', of which he wrote frequently, which played with the idea of a space removed of any image - a primary space, yet later his work was to move towards a perhaps more cerebral approach, with which he became more widely known for, and this is what I'll focus upon here.

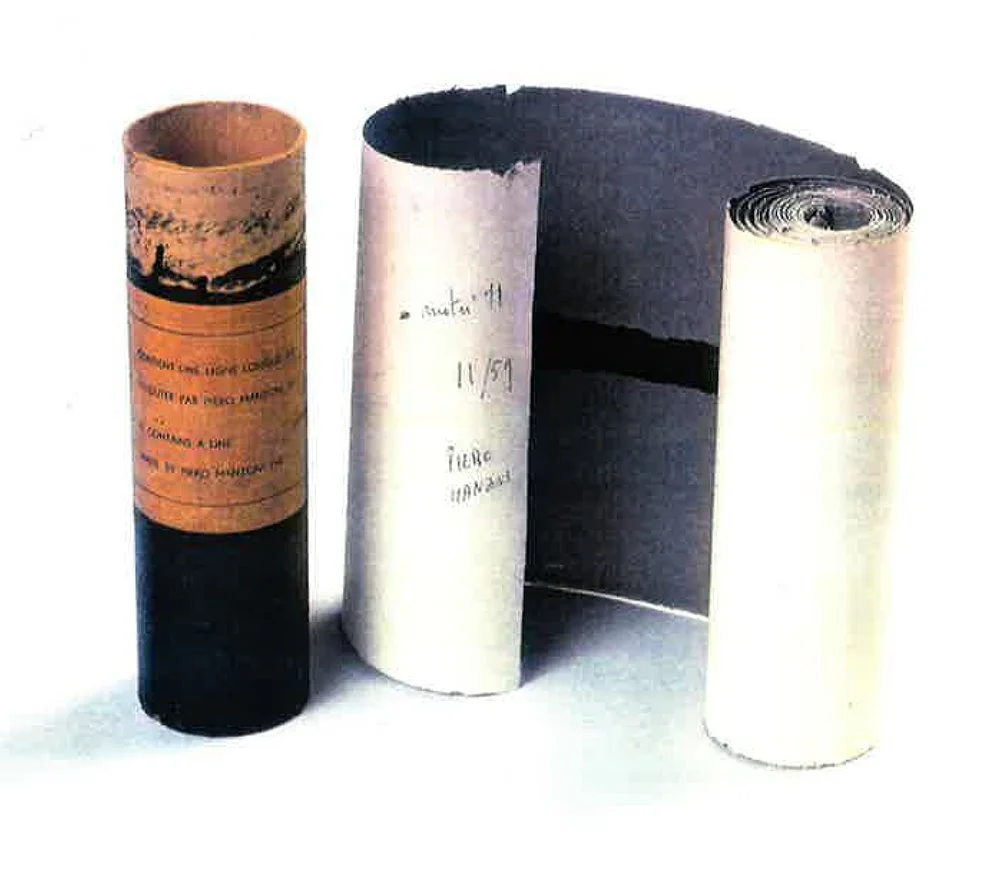

So how exactly did he go about doing this? Here we have a piece from the 'line' series from 1959, this particular one is the eleven metre line, and it consists of ink on paper in a cardboard cylinder. To draw attention to, and focus upon, the role of the line, the basic result of 'drawing', whatever that means, hints at some degree of universality between all activities. He was keen to stress this, (and here I'm quoting him), that 'the work of art has its origins in an unconscious impulse that springs from a collective substrata of universal values common to all men'. For example, with the lines, by the very fact that our consciousness is structured sequentially (it's linear), this, as Manzoni is suggesting 'is as basic as it gets', it is the most primary form of visual expression, the most fundamental type of 'mark', and also proof of human activity - it is a trace, and this theme runs throughout Manzoni's entire output. Yet why choose to encase it in this manner? To make it more of a consumable 'object'? Here we have the more industrial and elaborate '1000 metre line', of two years later. Perhaps it's suggesting a covering up, a hiding of this trace, the only proof we have to 'navigate' this aesthetic vocabulary of 'sequentiality' being language - the sign on the side which tells us what may or may not be inside. In a sense, the work relies heavily upon a 'belief' in the artist's statements - just because we can't see it, do we really believe that a line of a certain length is contained within? Does it really matter?

Piero Manzoni, Eleven Meter Line 1959

Piero Manzoni, Thousand Meter Line 1961

Another example of Manzoni's use of the previous vocabulary of 'art practice' is demonstrated by his 'signed eggs' pieces, which appeared in the infamous 'Consumption of dynamic art by the public devouring art' exhibition of 1960, in which the entire show was eaten in just over an hour. The egg, as a rather literal symbol of creation, in this context, artistic creation, frames its power onto the persona of the artist. Not quite in the grandiose manner of the artist 'playing God' but in the way that Manzoni, through his trace - his signature (his somewhat narcissistic imprint) is able to critique the recursal - like nature of art practice (which came first, the chicken or the egg, the artist or the artwork?).

Piero Manzoni, Eggs With Thumbprints 1960

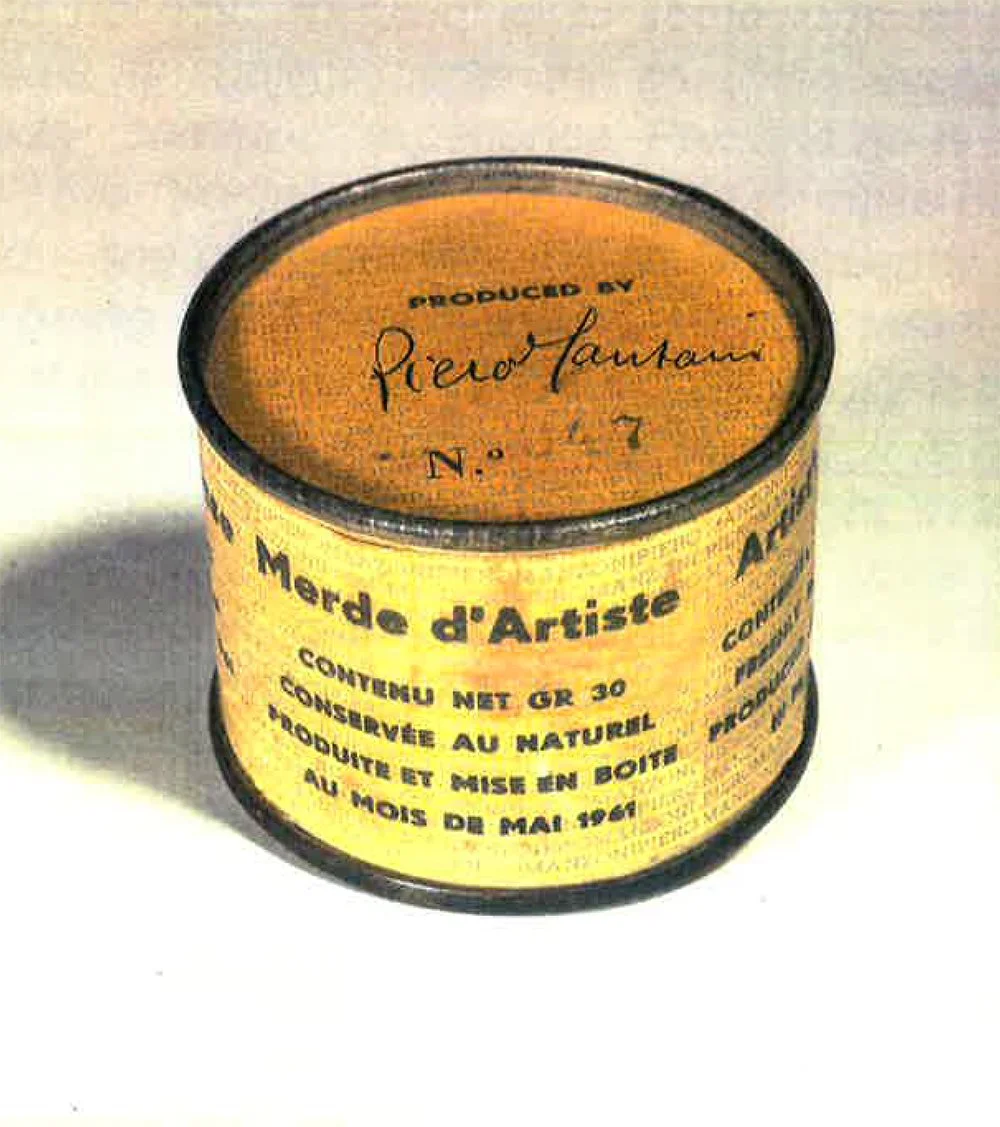

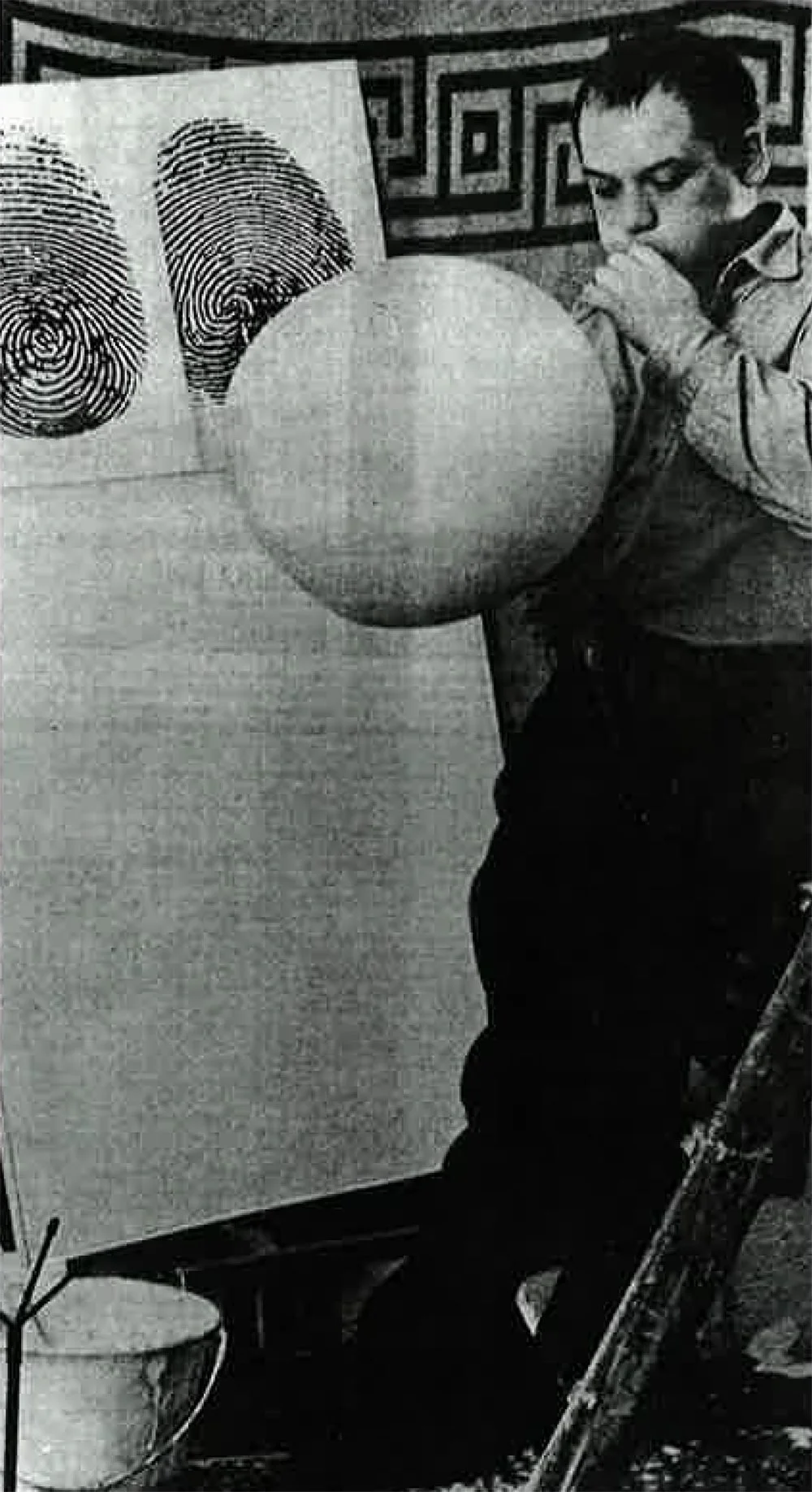

Perhaps the most infamously well known of Manzoni's works are the ones where he appears to dive into his own viscera and what he finds there subsequently proclaims as art. This is no better demonstrated than in his 'Artist's Shit' edition of 1961, which we see here. This was sold by weight at the same price as the day's price of gold, a perhaps somewhat obvious metaphor relating to the art market at the time. The shit here, again as a trace, a bodily waste product, fulfils the same purpose as the signature, creating the paradoxical situation of being unique and yet repeatable, a conveyor of value though produced at no cost. In alluding to some form of universality, Manzoni takes as subject matter the ritualistic, everyday theme of supposedly 'common' experience. Perhaps he is suggesting that through this 'waste' we might be able to make better sense of the world - one other such quote he is frequently associated with is his 'being is all that matters'. What appears to happen as a result of this celebration of the artist's bodily functions is a mythologised projection onto the artist himself. It is not the fact that 'anyone could do that' as Manzoni might indeed argue, but that it is the artist himself who has initially done it. Whether it's shit, breath, blood, paint on canvas, whatever, it is an all too essential mystique of the artistic process which creates this. I'd argue that it still remains unclear as to whether Manzoni was critiquing or celebrating this - he may just have fallen victim to the process he is trying to undermine.

Piero Manzoni, Artist’s Shit No. 47 1961

Piero Manzoni, Artist’s Breath 1960

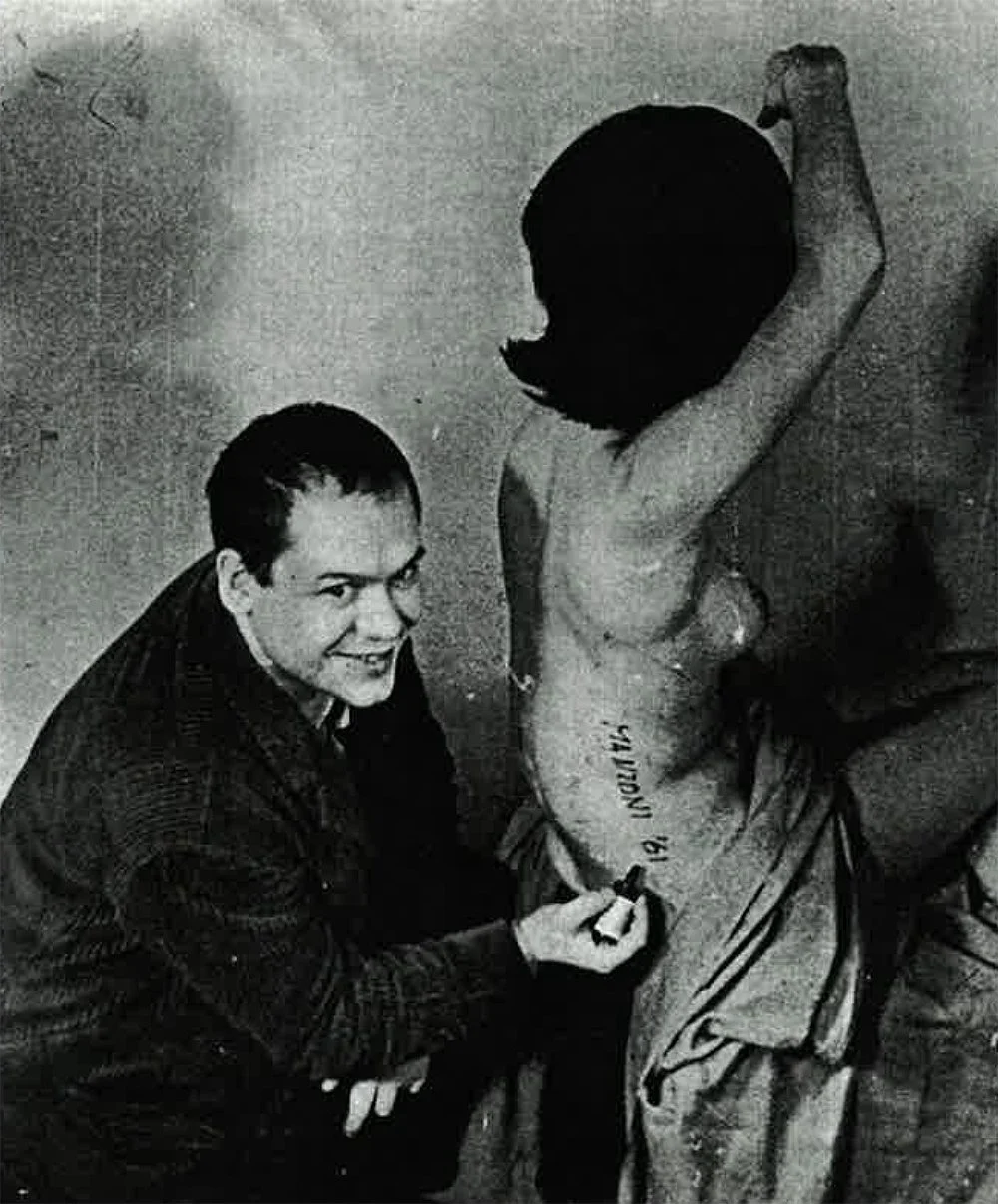

This 'mythologising' is taken to its conclusions with his 'body signing' and his 'magic bases' both of 1961, of which I've got a few versions here. He seems to be attempting to fix an artistic, aesthetic, spiritual and ultimately commercial value to his own activity, but I'd say that perhaps the spiritual aspect is the most important, particularly in terms of the subsequent mythologising. In these works he was attempting to embue certain objects with the transformational power of art (this again seems to have a familiar Duchampian ring to it). Returning to another 'art fundamental', Manzoni takes as his subject matter here the theme of the 'artist and model'. It is often an assumption that the models themselves are often mystified by the artistic process, and here seems to be no exception (note the somewhat exploitative similarities between this Brassai photo of Matisse, and Klein's use of the female form).

Piero Manzoni, Body Signing 1961

Brassai, Matisse With His Model (Undated)

Piero Manzoni, Magic Base 1961

In commenting upon artistic norms and rituals in this recursal - like fashion, Manzoni (as living myth) ultimately ends up as a sort of precusor to much of the subsequent conceptualism and so-called 'body art'. This brings me briefly to the contemporary artist Gavin Turk's methodology, which almost mirrors Manzoni's techniques of artistic interrogation, yet the primary discrepancy (aside from the obvious - the context) is that Turk is using the mythologised figure of Manzoni himself as subject matter in order to comment upon notions of authorship and originality (this is perhaps interesting in the light of my initial comments about Manzoni himself following in a tradition established by Duchamp, perhaps the same could be said of Manzoni's relationship to him?).

Yves Klein, Anthropometries Of The Blue Period 1960

Gavin Turk, Piero Manzoni (Detail) 1992

So to conclude, what can we say about Manzoni's work? In some respects, it almost begs you to say something which isn't redundant about it. Of course it's symbolic, of course it plays upon traditional assumptions of the discipline in relation to the spectre of Duchamp, and of course Manzoni becomes mythologised, as any artist producing work of this nature within a culture does (look at the press Marc Quinn had when he exhibited his blood head). The question I feel, and of course this is with at least thirty years of subsequent 'development' reflecting upon it, is how successful was he at performing this culturally sanctioned 'critique'? In preaching a now familiar cry of 'art for all', and attempting to use a common vocabulary which would be easily identifiable, did he in fact ostracize himself and entrench himself further within the realm of his own practice? Perhaps it's these questions that hold the real fascination of this artist's work, I'm still not sure.