Time Travel

Dissertation on the cultural, artistic and cinematic depictions of time travel, 1996

Programming Note: This was my main thesis work during the Art History components of my Critical Fine Art Practice degree at Kingston University, and was produced during my third and final year between Fall 1995 and Spring 1996. I have very fond memories of the extensive research phase of this project, especially attending seminars held by the H.G.Wells society at Imperial College. Going back over the work here has allowed me to illustrate the work with a greater fidelity, rearrange the attribution, and house everything in a single place. Needless to say it’s been a lot of fun to time travel back to this project over 20 years later.

Introduction

“What has our culture lost in 1980 that the avant-garde had in 1890? Ebullience, idealism, confidence, the belief that there was plenty of territory to explore, and above all, the sense that art, in the most disinterested and noble way, could find the necessary metaphors by which a radically changing culture could be explained to its inhabitants.” (1)

We currently live in a world which is constantly being divided up into infinitely small units of time. With the rapid growth of ever improving technology, it is perhaps true to suggest that as global communications heighten our awareness of the closer world community, the absolute speed at which this is being achieved only serves to bring attention to our culture's conception of time itself. To what extent does this situation differ from that of one hundred years ago?

This awareness is also currently being enforced by the imminent close not only of the century, but also of the millennium. This can be seen as being a particular moment of change, as if naturally aware of our anticipation of the future (in a sense it is felt as if our culture is on the brink of something, whatever that might be). The closest recorded parallel we might have to this experience would be the events of the late Nineteenth century. This awareness of time was being explored not only by scientists and mathematicians, but also by artists and writers. My initial argument will focus around how these explorations came to become popularized.

Linda Dalrymple Henderson, in her excellent book, The Fourth Dimension, attributes this popularisation to three main sources - philosophy popular at the time, Theosophy, and science fiction stories. Dalrymple suggests that, due to the increased awareness of Einstein's general theory of relativity, the fourth dimension became known as time rather than previously as an extension of space. Her early and perhaps most important discussion centers around the writings of Charles Howard Hinton, who believed that to see the fourth dimension (it is rarely described as time) was in some way to experience a true reality, and who was the first to propose our notion of it as something non-geometric. He more importantly also proposed electricity as a fourth dimensional phenomenon, as he believed that positive and negative currents could only be made to coincide by moving them through time.

What appears to be happening is that complex philosophical thought is attempting to be explained through the vocabulary of the everyday occurrence. H.G. Wells was to pick up on this idea in a more simplistic manner (Wells was trained at Imperial College, London, and would have been aware of these ideas being discussed), and proposed the fourth dimension as a place or temporal means of reaching another era, as well as being a vehicle for allowing him to express his social theories. Therefore this initial proposal of a means of addressing the fourth dimension became mediated to a wider audience through the use of stories. In focusing upon notions of the fourth dimension and their subsequent sanitization, I have chosen to explore the premise of time travel.

Stargate (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer / Carolco Pictures 1995)

Aside from the recent rash of big-budget cinematic time travel re-evaluations such as Stargate (1995) or Timecop (1995), this study is also timely due to not only contemporary scientific debate proposed by among others, Stephen Hawking (2), but it is also one hundred years since the invention of time travel, as heralded by the publication of H.G.Wells's novella The Time Machine in 1895.

“Whether by accident or by necessity, the age of technology is concomitant with the age of desire, rendering postmodernity peculiarly susceptible to the romance of people for their machines.” (3)

In giving birth to this new genre of science fiction (albeit with his usual sociological slant), Wells made possible, in picking up on the contemporary scientific thought of his time, a method of focusing upon, and making visual, an abstract phenomenon. This is particularly relevant due to the time of his writing, as the story itself becomes emblematic of the cultural and scientific context of the Western world in the late Nineteenth century. Through employing the mechanical device of time travel, his infamous time machine, he demonstrated the fluidity of such (previously) apparently rigid abstract concepts. Engaging with such a concept, as illustrated by Wells and subsequent time travel stories, involves coming into contact with some form of anomalous energy field, which serves to demonstrate how the novella might be situated in terms of cultural thought concerning magic at the time. The place of technology within the context of supposed evolutionary development (or the faith we have in this scientific achievement) will also come into consideration through a questioning of this rigidity. Wells's The Time Machine demonstrates and reflects the false sense of optimism symptomatic of the late Victorian bourgeoisie as to the role of this technology and indeed science in general, in shaping the future.

The Time Machine (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer 1960)

As a result of this questioning, Wells also created a literary and cinematic theme which has lent itself to creating interesting technological paradoxes, and in terms of my own analysis, it is perhaps also important to discuss the novella's role in the context of one hundred years of subsequent technological development. Paradoxically, in time travel stories, this technology is not seen as particularly liberating, with time travel stories generally being rendered tragic, the time traveller either trapped outside of his own time, or being sent off into oblivion by unknown means (4). What is suggested by the allure of the time machine is that it often holds dangerous consequences for those who use it.

Even Wells, unfortunately, and perhaps ironically, by inventing the notion of time travel, has also become victim to what is known as Recursal Science Fiction (5). Often fused with the character of the time traveller himself (as in films such as Time after Time of 1979), he becomes the cinematic emblem of the scientific buffoonery now (perhaps perpetuated by literature of this nature) generally associated with Victorian England.

In ascertaining the means by which the fourth dimension may have become sanitised, it will be important to examine the cinematic and to a lesser extent literary legacy of time travel stories, as it is important to note that this how we have come to know of time travel today, within the vocabulary of science fiction. Modern authors however, have tended to be interested in time travel for its own sake, with little attention paid to the actual method by which the travel is achieved. It is primarily used as a device for exploring paradoxes and decontextualizing people.

After the initial interest surrounding Wells's novella, it was not until the mid twenties that the science fiction pulps really began to explore the subject again in any depth. Subsequently, it was later the fifties and sixties which witnessed a deluge of time travel interpretations. The interesting matter here is that these were both eras of machine dominated post war optimism. There was a growing awareness of the increasing role of technology, and a particular cultural focusing upon the role of machines in general (as demonstrated by increased automation in both the home and the workplace).

As interpretations of these growing social phenomena and the possible need for escapism (perhaps mirroring the escapism brought by this technology itself, in particular television), time travel stories are well reflected by fifties American science fiction, which exploited (however consciously) the increasing Cold War sense of paranoia within the American people (6), in particular, the susceptible young market of drive-in teenagers. Depictions of invasions, apocalypses, abductions and mutations (typically the stuff of such low-budget B-Movies) are not really that far removed from the growing reds under the bed suspicion inherent in the new atomic age. Indeed, Wells's 1895 novella showing concerns surrounding Victorian class division is perhaps markedly different from American George Pal's cinematic 1960 holocaust driven interpretation of the same text.

Of course, the allure of actually being able to travel through time is irresistible, and the theme, through its cinematic proliferation, is still one which exists on the edges of the one day it will be possible to... genre of speculation. That is not to say that it has not been claimed to be possible, merely in a far different sense than the initial use of Wells's machine. Dream visions, mesmeric trances or states of suspended animation have all been claimed to have allowed time travel to take place. Traditionally claimed as religious phenomenon, these psychological anomalies have often been surrounded by scepticism. The previous validity of such claims is particularly interesting in the light of reading Wells's novella as a puzzle, designed to reveal a parlor trick hoax, as I will explore in chapter one.

Creating rationales or explanations for such anomalous behavior (which appear to blur the distinction between the fictitious and the feasible) demonstrates one of the fundamental traits of the idea of time travel, that of the paradox. For example, if time travel is ever possible, why don't we already know about it? Here, the usual question posed is, what would happen if you went back in time and killed your parents, thus preventing your own existence?

“Although no-one is sure what would happen if you created a paradox, it is highly unlikely (and goes against the laws of physics for our world) that matter would just disappear into thin air.” (7)

There is often this element of pseudo-physics within the genre of time travel stories, in a sense trying to return to the initial speculations of writers such as Hinton, yet this is perhaps primarily employed to bring some degree of credibility to the subject, to allow it to enter the realm of the somewhat believable.

One interesting facet of time travel's inherent pseudo-science is the questioning of time lines. These attempt to explain and illustrate how movement through time is possible, however, there are two opposing viewpoints. What is disputed is the method of the supposed flow of time. The classical theory of Isaac Newton suggests that there is only one existence, and therefore a single timeline, along which things move until they cease to be. This theory reinforces the problematic temporal paradox of being able to prevent your own existence (8). Conversely, the more contemporary quantum view is that time exists as a multiverse of infinite possibilities, with time travel being able to exist between any of these times. Yet how does this actually work? The theory suggests that with every decision made, there is a rejection of a multitude of other possibilities which would have led to separate and different realities. Therefore we have this ongoing fracturing process of constantly creating new universes of possibility (9).

“The many universes interpretation of quantum mechanics solves a lot of time travel paradoxes. A time traveller can make any change in the past he/she/it wants to without endangering their existence because they came from a different universe whose timeline is untouched by their meddling.” (10)

During the course of this dissertation, I will explore the themes and anomalies raised through such meddling with time travel, and focus upon how it might be proposed as an emblem of sanitized cultural thought. Integral to this, will be a re-examination of the scientific and cultural problems being explored in this manner at the time of, and since, his writing of The Time Machine. I intend to begin with a close re-examination of the origins of time travel in Wells, and attempt to rationale how the novella might be re-interpreted in the light of one hundred years of supposed progress.

Footnotes

Hughes, Robert: Quoted in Smells like Avant-Pop, Internet Modernism Homepages

A recent description of these contemporary scientific debates was described by Peter Millar in his article Time Travelers reach for the Stars (Sunday Times, 8th October, 1995)

Hanson, Ellis: Technology, Paranoia and the Queer Voice, Screen Summer 1993

A good example of this is Robert A. Heinlein's By his Bootstraps which is still praised for its originality in dealing with the time travel genre. This first appeared in Astounding Science Fiction in 1941.

Recursal Science Fiction describes the use by science fiction of elements from its own past. This is perhaps a particular phenomenon of the postmodern era, and demonstrates the problems inherent in trying to combine historical elements.

This is also demonstrated by the developments in Modernist theory at the time, and its focusing upon the more social aspects of artistic practice. Francis Frascina's Pollock and after - the critical debate (Harper and Row, 1985) documents this and how art of the Modernist nature was used in methods of cultural imperialism.

The Terminator Internet Homepage: Time travel questions

This was the simple premise of James Cameron's film The Terminator (1984), whereby a cyborg was sent back in time to prevent a future leader from being born by trying to kill a young girl (who was to be the future leader's mother).

A good explanation of this is provided in its bizarre entirety in the opening minutes of Richard Linklater's Slacker (1990), in which a young man relates to an indifferent taxi driver the precise nature of how multiverses are created, and how he had just experienced the dilemma of deciding which universe to take whilst waiting at the bus station.

Ref. 7

Chapter One

“Our perception of time is said to depend on principles of nervous action. The slow decline of nervous activity after a presentation (such as the after images we see after looking at a bright light) gives rise to our sensation of the present which then fades into a sensation of immediate past as the nervous action passes into memory and is succeeded by a new presentation. Our perception of time is thus produced by a continual succession of nervous sensations, or feelings.” (1)

In brief, The Time Machine (2) concerns an inventor (whom we only know as The Time Traveller) who has produced a device for moving forwards and backwards in time (3). After discussing the schism between space and time (such as their similar properties of extension), he demonstrates a small prototype of the device to a group of dinner guests, whereby it vanishes into the past (or the future), never to return. In doing this, he explains that he is conscious to bring the element of time into the vocabulary of visible, physical space.

On the occasion of a second dinner party approximately a week later, the time traveller enters, clothes tattered, apparently having just returned from the future using a larger, full scale and functional, time machine. He then recounts to his dinner guests what has happened to him during his week's absence. The enfolding tale tells of the journey on the machine itself, and his encounters with the divided world of 802,701, where the Earth's inhabitants have evolved into two distinct social groups, the Eloi, who are playful, childish and passive, and the sinister underground Morlocks, who prey on the Eloi in order to survive. These two groups are often considered to be parallel to Wells's concerns as to the sociological class structure of Victorian London, where there was perhaps a fear of the lower, working classes.

After recounting the tale to a somewhat disbelieving audience of dinner guests, he then takes off on the machine, only this time never to return.

Begging a sequel (it has been argued that had Wells lived in the latter half of this century, publishers would have made him write a more saleable trilogy), the cliff hanger ending has spawned many second installments, by various authors, none of which appear to have the same mystique as Wells's original (4). All focus upon the machine, as it is primarily the machine itself which is the most important element in the story. If we are to read it as emblematic of optimism inherent in scientific knowledge at the end of the Nineteenth century, (due to its increased social emphasis since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and the ever growing notion of faith in machines becoming more and more common in approaching not only a new century but a new millennium), it is suggested by Wells that the possession and use of such knowledge is ultimately fallible and certainly does not equate with any sense of social power.

This can be explained through the actions of the time traveller and the fact that the time travel experiment he is conducting is ultimately doomed, as he ends up (as far as we know) as rather obsolete, ultimately disappearing into oblivion on his machine. Even after a hundred years of scientific developments since this speculation (5), it would seem that we are perhaps still no closer to harnessing an element of nature which controls our consciousness (6). Wells appears to be questioning this mass sense of a supposed faith which we have in scientific achievement and machine technology in general. Where does this faith come from? Could it spring from an inherent desire for perpetual change?

It is true to say that machines play a far greater role in shaping the everyday of 1995 than of 1895, but does this greater automation merely serve to push people further away from each other rather than vice versa? (think of the greater isolation of individuals brought about by using computers). This is particularly relevant in terms of the time traveller (who could be described as the man of science) having to ally with one of the two dominant social groups of the novella in order to affect any degree of change (7). It is the political and social liberalism of such knowledge which is proven to be either futile (on its own) or useful (when effectively distributed).

Rejecting such titles as The Time Journey or The Time Traveller, the machine, after all, is the title of the book. However, if we are to look closely at Wells's descriptions of the machine, and the situations in which it appears, it is perhaps possible to uncover one possible hidden agenda of his story.

The machine itself is rendered with a particular air of unreality by Wells (perhaps returning the reader to an awareness that the experience is after all, only a work of fiction). By combining familiar aspects such as descriptions of a brass frame, ivory bars and metal studs with vague and undisclosed elements such as a mysterious transparent crystalline substance which appears to be the central working element in allowing the machine to actually function, this degree of unreality heightens the sense of magic or theatricality in the time traveller's activities.

In only describing small details of the machine as opposed to any grand overall account, Wells employs a clever literary device of allowing the reader to subjectively render their own mental image of the apparatus. In only giving reductively sparse amounts of information, this tends to lead to possible misinterpretation, although the reader does feel as if the time traveller is actually being quite specific in describing the machine. Through this generalizing, vagueness leads to a more interesting hypothesis that the machine could be no more than an elaborate and novel design of bicycle, of which I will discuss later.

The notion of the machine is a subjectively mental one, being fixed in our memory by the title of the book. Therefore, the role of the machine (in a sense a personification of the new machine age), becomes important in discussing the scientific developments which Wells is perhaps debating.

Why critique Victorian norms with a story about the future? Here the role of science is used as a means of ending the so-called divisions. In 1895, science was becoming increasingly prolific in proposing rationales for what had previously thought to have been the work of God. This is where the issue of faith in scientific explanations becomes questionable, as science began to provide explanations for natural events in the world.

For example, after Darwin's interpretation of the book of Genesis, it became difficult to still believe that the world had been created in only six days. Yet the use of this new scientific knowledge by the often bewildered and decontextualized time traveller (the man of science), merely demonstrates that perhaps it is not being put to any useful purpose at all. With his background at the science colleges of South Kensington (he knew Darwin's friend T.H. Huxley), Wells may also be suggesting that the scientists of the day were just as bewildered in the face of so much scientific and possibly social 'uncertainty'.

As a symbol of the human role within scientific development, the time traveller is almost rendered generic. He is science, and has been given the somewhat Promethian task of solving the future world's problems on his own (it is noticeable that in the world of 802,701, there appears to be no need for science, so the traveller assumes that there has been an evolutionary degeneration). It is debatable as to whether the traveller is of any distinguishable class, yet he does feel a particular affinity with the Eloi (the futuristic and literally upper class). Even though he is disdainful of their lifestyle, he is perhaps more horrified and repelled by the crude, lower class Morlocks. Initially having no allegiance to either group (emphasizing his difference), the liberal scientist joins what could be termed as the bourgeoisie of the future, but only serves to disrupt their already well established norms.

“A man without social and economic ties is the true perceiver of social reality.” (8)

The time traveller's otherness or separateness in the world of 802,701 can be related to Roland Barthes' interesting thoughts on the role of the bourgeoisie within a culture, particularly with reference towards his comments concerning their alleged anonymity. The complete deception of the dinner guest character of Hillyer (who is not only representative of the Victorian bourgeoisie, but also the narrator), demonstrates the naive optimism of bourgeois society ridiculed by Wells. This is interesting in the light of the traveller as a generic representative of scientific man.

“This strategy takes the once revolutionary ideology of the bourgeoisie, with its emphasis on the power of mankind to transform nature and direct history, its emphasis on the new, free individual, and turns it into its opposite, emphasizing the permanent quality of nature, of bourgeois social organization. The consequence is the creation of a sense that mankind can do little to influence or change historical development. In this sense, Barthes says that bourgeois Eternal Man turns out to be Irresponsible Man or, as he finally terms him, Derelict Man.” (9)

Thus the novella proposes to negate the myth of progress by comparing bourgeois feelings of powerlessness, frustration of hopes and its false sense of idealism with those of equal measure in the name of science. As generic man the time traveller starts out as an immortal (having created a revolutionary device), yet becomes irresponsible through his futuristic experiences and perhaps becomes derelict in the sense of the final stages of the book where he disappears forever into oblivion.

There is a certain responsibility inherently given to scientists within Western culture (through whatever form this may take). Wells may be alluding to the fact that whatever knowledge is discovered, it will eventually become obsolete as it is transcended by more advanced theories and practices in progression towards the future. Could this desire for transcendence also be seen as a metaphor for human progression itself? What happens to the old ideas?

This issue of the traveller's final disappearance brings me to discuss the role of Wells's own autobiography in the work. Prior to writing The Time Machine, Wells had been producing essays which explored the notions of cryptograms and hidden symbols. He also had a keen interest in Victorian stage and parlor magic, these being incredibly popular at the time. Coupled with this, it is even possible to correlate the traveller's final disappearance with that of Wells in 1901, whereby he vanished for two months on his bicycle without informing anyone. The fact of Wells's grounding in psychology and perceptual analysis through his education and subsequent interests, points to another possible reading of the novella in terms of cryptograms interwoven into the text.

There are eleven references to puzzles during The Time Machine, which reveal anomalies in the time traveller's account of the events and point to the possibility that he has merely hoaxed his dinner guests with an elaborate stage trick.

“No. I cannot expect you to believe it. Take it as a lie - or a prophecy. Say I have dreamed it in the workshop. Consider that I have been speculating upon the destinies of our race, until I have hatched this fiction.” (10)

Recent debate at The Time Machine International Symposium proposed how to approach this cryptogram issue. It is suggested that there are two distinct parts to the novella, the inner and outer frameworks (the inner being the world of 802,701 and the outer being the Thames Valley dinner party), the solution of the latter revealing that the story is no more than a hoax, with the time traveller having dreamed his vision after having returned to his workshop from a exhausting cycling excursion.

It is true that the traveller has been somewhere during the period of his absence (due to his state upon return), but what is perhaps more plausible an explanation than a trip to the future is that in the time he has been away he has simply been learning to ride the bicycle (again there are distinct similarities with the descriptions of the journey in The Time Machine and the text of an early tricycle essay of Wells's entitled Specimen Day (11)). After all, the vague descriptions of the machine (for example its framework), and its use creates a spinning and jolting motion. During this time away he has an accident and damages the machine, yet upon his return to the lab, exhausted, he falls asleep and his previous thoughts about the future and his subsequent cycling experiences mix together in a state of self-loss, a dream.

“Dream-thought is illogical and confused, and liable to invent details to cover up lapses in memory.” (12)

Dream visions or mesmeric trances (again often the stuff of time travel stories) were also being explored in some detail during the 1890's by such psychoanalysts as Freud, George Trumbull Ladd, and Herbert Spencer, as a means to possibly understanding human behavioral patterns. It could be proposed that before this date, most anomalous behavior was accounted for by the church, visions taking on holy or spiritual implications. Science appears at this time to start finding a series of rationales explaining this behavior, and therefore undermine the existing theological conviction that God might be at work.

These late Victorian principles of psychology and visual perception underpin the outer framework. This would also help to explain the disappearance of the prototype model time machine and the traveller's final departure as optical illusions popular also at that time (Victorian magic's use of the Sphinx floating head trick being similar to this (13)). Can the traveller therefore also be seen as a magician? This relates to the diminishing role of the church at the time (as seen in the context of Darwinism) as magic provided staged visualizations of the anomalous. In the context of 1995, it is obvious that there is no divine intervention during a trick, although the performer might have the audience believe so. We are told that the small time machine produces a rapid spinning motion, perhaps thus creating no more than the same form of optical invisibility seen with spinning bicycle spokes.

“Our ideas, feelings and volitions take part in determining how we shall see the spatial qualities and relations of any object ... Or - to say the same truth in more popular phrase - within given limits, we see what we think or imagine ought to be seen; what we are expecting to see; and what by an act of will determine to see.” (14)

Some of the more interesting anomalies created by Hillyer's narration of the tale include the initially arbitrary choice of the date of 802,701. If one is to take the first letter of the written form of this date and treat them as an anagram / cryptogram, we find that it does in fact spell out The Host (in a sense, providing a metaphorical link for the dinner party being a modern day last supper). This perhaps sounds like an irrelevant rationale, but due to the date being so arbitrary, it merely begs a questioning of why?

The result is a focusing of attention on the role of the traveller, whose perhaps dubious integrity we have already brought into question. The design of the book is therefore as an intellectual puzzle, which purports to use the device of technology to compress time but which really is little else than an illusory expansion of Wells's contemporary perceptual analysis.

“Dreams are the imperfect and exaggerated interpretation by the somnolent mind of the sensations that affect it, together with the flow of suggestions that naturally follow such impressions.” (15)

One of the more interesting issues in Wells's novella is the exploration of Neoteny, Kirby Farrell's discussion of which can be found in appendix c. Neoteny is particularly characteristic of the young, but Wells seems to suggest that they are also those of the feminine, as demonstrated by the only one of the Eloi to be named, the meekish, playful Weena. Femininity is played down during the novella, reflecting Wells's own view of the diminished role of women in late Victorian society

Weena is the only member of the futuristic species which the time traveller actually gets to know. Her passiveness and utter submissiveness (whether deliberate or enforced) in the face of such male scientific questioning from the traveller perhaps reflect the ostracization of women from the strand of society which devoted itself to science. Neoteny as prescribed by Wells proposes play (in a sense, of a particularly domestic nature) as one of the basic developmental processes, and therefore it is obvious to see why he has structured the novel as a series of cryptograms. Is Wells attempting to educate through this mental exercise?

In any discussion of evolutionary projection, Nietzsche's speculations are also incredibly important, and particularly interesting in the light of technological and scientific development, his text of 1885 entitled Thus Spoke Zarathustra is certainly in keeping with the context of alleged pedagogy in Wells' writing.

“Man, who transcended the animal condition by means of technology, must free himself of the same technology to arrive at the superhuman condition.” (16)

However, whether or not we are to take the traveller's account as real or merely a description of a dream, it is particularly noticeable that Wells places him at such a point that he is somewhat separated from his peers, or as Nietzsche might have termed them, the herd. Through the vocabulary of pseudo-determinism, Wells' time traveller might aspire to the Nietzschean conception of the superman (Ubermensch), the next step in human evolution. This is interesting in the context of the time traveller as a representative of science (and probably therefore Darwinism) and its inherent rationales against the behavior of a God. This implies a decline and loss of moral faith, as what is being proposed is that there is no longer a need for a conscious, creative force, as what appeared as order could now be explained as random change.

For Nietzsche, Darwinism meant that the Earth was devoid of any transcendental meaning, the goal of humanity being to create higher species. Can the time traveller, in some way be seen as transcended, even as the modern Zarathustra?

“When Zarathustra arrived at the nearest town which adjoined the forest, he found many people assembled in the market place; for it had been announced that a rope dancer would give a performance.

And Zarathustra spoke thus unto the people:I teach you the superman. Man is something that is to be surpassed. What have you done to surpass him?

All beings hitherto have created something beyond themselves : and you want to be the ebb of that great tide, and would rather go back to the beast than surpass man?

What is the ape to man? A laughing stock, a thing of shame. And just the same shall man be to the superman: a laughing stock, a thing of shame.

You have made your way from the worm to man, and much within you is still worm. Once you were apes, and even yet man is more of an ape than any of the apes.

Even the wisest among you is only a disharmony and hybrid of plant and phantom. But do I bid you become phantoms or plants?Lo, I teach you the superman!” (17)

Therefore, through employing the device of time travel, Wells uses this to critique the optimism inherent in the 1890's discussion connected with the fourth dimension, possibly proposing that installing faith in something (in this context, science or religion) is ultimately flawed. Time travel becomes a method by which these ideas can visually exist. Wells's text was perhaps the first to crystallize this into a recognizable format for a wide audience. In expanding upon this device of Wells', it may now be possible to suggest how the cultural ideas explored in The Time Machine have in some way become sanitized, due to their increasing association with the anomalous itself.

Footnotes

Sommerville, Bruce David: The Time Machine - a chronological and scientific revision, The Wellsian Winter 1994

H.G. Wells' The Time Machine (Everyman's Library, 1992 edition used during this project) began life as a three part serialization in The Science Schools Journal of 1888, where it was entitled The Chronic Argonauts. Initially written whilst Wells was suffering from an attack of tuberculosis, the primary text was revised many times before becoming the renowned 1895 The Time Machine. Even from this point, until his death in August 1946, Wells was constantly tinkering with the text of the novella, although not enough as to radically change the chronological framework in any great depth.

This goes against many of today's cinematic time machines, who require movement in space as well as time. The most notable time machine which relies upon movement in space for it to work is that featured in Robert Zemeckis' Back to the Future cinematic trilogy. In this particular case, the time machine, built from a Delorean car, is required to accelerate to 88 mph in order to achieve time travel.

Some of The Time Machine's sequels have been :

Baxter, Stephen : The Time Ships

Lake, David : Morlock Nights

Priest, Christopher : The Space Machine

I would maintain that the discrepancy between these and Wells's original probably lies in the fact that they don't have the Victoriana presence or indeed context of the first book, which I'd see as being vital to its success.Perhaps the more memorable of these were the ones which might have seemed inconceivable during the previous century - Man on the Moon, the atomic bomb, advances in medicine, airplanes, cars, televisions etc. - notably many of these we now tend to take for granted as part of everyday living.

We still live in a society dominated by time - with no foreseeable way of changing this.

The Eloi and the Morlocks of Wells's novella can be seen as representative of the Victorian class structure of the time, particularly in London. The Eloi are literally the Upper class, living a serene existence of near-utopia, whereas the underground and animalistic Lower class Morlocks seem banished to live a harsh existence 'out of sight and out of mind'. The irony is that what the Eloi enjoy during their brief lives, as Kirby Farrell puts it, they pay for on Morlock dinner plates - the Morlocks are cannibals.

Wasson, Richard: Myths of the Future - The Time Machine, The English Novel and the Movies, Frederick Ungar Inc. 1981

Ref. 8

Ref. 2 (The Time Traveller)

Specimen Day: The Science Schools Journal No.33 (October 1891) - A description is contained in Ref. 1

.Robertson, Ritchie: Modernism and the European Unconscious, Peter Collier, ed., Cambridge Polity Press, 1990

This trick dates from around 1875, a description of which states:

”Probably the most common of all the illusions which depend upon mirrors is the talking head upon a table. The apparatus consists only of a mirror fixed to the side legs of the table. The mirror hides the body of the girl, who is on her knees and seated on a small stool, and reflects the straw which covers the floor so as to make it appear continuous under the table; likewise it reflects the front leg of the table so as to make it appear at an equal distance from the other side and thus produce the illusion of the fourth leg. It also reflects the end of the red fabric hanging in front of the table and thus makes it appear to hang down from behind. The visitor stands only a few inches away from the table and head. Such proximity of the spectator and actor would seem to favor the discovery of the trick, but on the contrary, it is indispensable to its success.”

Albert A. Hopkins: Magic - Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, Benjamin Blom, New York, 1967, original 1897)... any real body must have extension in four directions : it must have length, breadth, thickness and - duration. But through a natural infirmity of the flesh which I will explain to you in a moment, we incline to overlook this fact. There are really four dimensions, three of which we call the three planes of space, and a fourth, time. There is, however, a tendency to draw an unnatural distinction between the former three dimensions and the latter because it happens that our consciousness moves intermittently in one direction along the latter from the beginning to the end of our lives. (The Time Traveller, Ref. 2)

Wells, H.G.: Quoted in Ref. 1

Ciment, Michael: Quoted by Elizabeth Boggis in 'That was Tomorrow', Victoria and Albert Museum - National Art Library Thesis, 1994

Nietsche, Friedrich: Thus spoke Zarathustra, Penguin Books, 1968 Edition, original in 1885

Chapter Two

Time travel (as an extrapolation of four dimensions), appears to be dependent upon an altered state of consciousness, and it could be suggested that dreams, trances, or even near-death experiences are all mild forms of 'real' time travel. This is particularly the case in terms of premonitions and the mysterious, still unexplainable phenomenon of deja vu. Distinct from 1895, this type of phenomena is not really given much creedance in 1995, as in some ways it has just become commonplace to accept the fact that it 'happens', yet as this phenomenon had previously been accounted for by the church (anomalous behaviour mildly relating to Biblical texts), experiences of this nature were often seen as spiritualist intervention. The flux between these two states seems to have started during the 1890's whereby science had in fact become the new 'faith'. It was itself even using a theological vocabulary.

The research of Dr. Serena Roney-Dougal appears to propose that limited precognition is perhaps brought about by the neural hormone secretion of a chemical known as Seratonin (1). It is already well known that emotional states are related to the flow of certain hormones which effect the neural network, yet one state at which supposed 'time travel' allegedly occurs is often termed the 'Oz Factor'. This term was coined by Jenny Randles, a writer on anomalous behavior (2). As she describes it, the Oz Factor results in feeling a sudden isolation in space, where, in perceptual terms, all the normal ambient sounds and sensations tend to recede and eventually disappear. This is often attributed to the human consciousness in some way tuning out all forms of sensory input and superimposing one view upon all the others. This view is perceived as time travel.

If we relate back to Wells's novella, this would certainly fit the time traveller's account of his isolation both in literal terms when traveling through time and perhaps in a more metaphorical sense when attempting to coexist with the people of 802,701. His real feelings of timelessness or spacelessness are attributable to his somnolent or daydreaming mind receding from its immediate environment, (the time traveller, and therefore also Wells, is keen to stress that time travel is possible only through altered consciousness, and that the machine does not move through space). Wells, in his education of psychology and neural behaviorism (3), is likely to have known about these theories.

The uncertainty of experience is the key to understanding how what we know as time travel (both literal and fantastical) might appear to work. It is perhaps true to say that time is an artificial concept imposed by the human consciousness in order to structure a linear phenomenon. This was explored by Heisenberg, whose 'Uncertainty Principle' relates that, at the quantum, or sub-atomic level, you can never measure or predict anything 'for sure', but merely speculate within either a broad or narrow range of possibilities (4). This can also be said of much art historical practice, which is also unable to in a sense 'de-subjectivize' itself from the issue of critiquing work.

It is arguable that much of Modernist theory attempted to in a way, remove this quality and engage in a purely objective manner, in much the same way as one is able to appreciate a piece of music. Heisenberg questioned the possibility of a fundamentally observable reality due to the experimenter's active part in actually conducting the experiment. To simplify this, the experimenter can never truly perceive a 'reality' due to the nature of his looking (for example, light affects our perception of all things, so the object under examination is the object 'plus' the element of light upon it). In a sense, this creates a simple paradox. We know of a reality, yet this is marginally different from our distorted observable reality.

Perhaps this notion of perceptual uncertainty is problematic when applied to technology (after all, it is humans who program computers), yet if we are to take this uncertainty as corollary to 'real' time travel (or the conception of it as dreams, trances etc.), it is possible to suggest how technology might induce this state, by looking at the events which allegedly took place in a Philadelphia Naval Yard on August 12th 1943. The place of stories such as this occupies a strange position within western society, as there seems to be a mysterious desire to perpetuate these myths about the anomalous. This could be seen as one way in which our culture has replaced the mystery once catered for by religious activity (although it is incredibly marginalized).

The information surrounding the 'Philadelphia Experiment' primarily concerns the testimony of American ex-serviceman Al Bielek. Bielek's story relates that, after having been born as Edward Cameron in 1916, he and his brother Duncan enlisted into the US Navy in September 1939, whereby they attended a ninety day training school for so-called 'special assignment' Navy personnel. This consisted of attempts to render a ship radar invisible. After successful tests in Brooklyn Naval Yard in 1940, the project then moved to Philadelphia Naval Yard.

The experiments of 1940 to 1942 achieved this invisibility with unmanned equipment, yet on the 12th August 1943, a manned USS Eldridge not only achieved radar invisibility, but also optical invisibility, the only trace of the ship being a line in the water. When the equipment inducing this invisibility was subsequently turned off, the ship re-appeared, yet with the crew either driven insane by the experience, or more horrifically, actually fusing with the hull of the ship. Al and Duncan apparently survived the test by jumping off the side of the ship in mid-experiment.

Al later stayed with the Navy until he was charged with espionage in 1947 and, rather than be tried, was transferred to Fort Hero military base at Montauk, Long Island. Here he becomes involved with a new project using the same technology (this is known as the Phoenix Project). In this experiment, he apparently manages to 'time shift' to 1983, where he loses his memory, has his age regressed to one year old, and is then sent back to 1927 to be plugged into a new family (the Bieleks) as the substitute for a dead son. He then regains his memory of the entire experience in January 1988 after watching 'The Philadelphia Experiment' (1984) (5).

He has subsequently told of the continuing experiments into changing the nature of time consciousness which occurred at the Montauk base until about the mid eighties. These are documented by Preston B. Nichols (a technician who allegedly worked on these projects) in his book entitled 'The Montauk Project', which has become synonymous with the perpetuation of anomalous myth (6). Nichols grounds the book in dense scientific language concerning how the necessary energy field (the artificially produced 'aura') was created. He seems keen to dwell upon these explanations as if to, in some way, give creedance to his story. As I mentioned before, this is often employed as a cinematic or literary device to make the tale seem 'believable'. In saying this, it is probably the reason as to why I remain skeptical (if the nature of the material is esoteric enough, it is easier to take it as 'truth').

However, the Montauk Project involved some of the same technology which was employed during the Philadelphia Experiment, which has now allegedly been developed for use on stealth fighter aircraft. This technology's purpose was to create an 'energy field' which was transposed through the mind of psychic Duncan Cameron (the same one from Philadelphia) to produce a particular 'bending' of time. Nichols talks at length as to how this was technically achieved, yet the primary instrument used in this was known as the 'Montauk Chair'.

This worked on the principle of a mind reading machine, which picked up the electromagnetic functions of the tuned human mind and translated them into a readable format. The device actually read what Nichols terms the 'human aura' (7), the electromagnetic field which surrounds the body. These thoughts theoretically manifest in this aura in a similar way to how a voice is carried through radio waves.

“Duncan would start out sitting in the chair. Then, the transmitter would be turned on. His mind would be blank and clear. He would then be directed to concentrate on an opening in time from say, 1980 (then the current time) to 1990. At this point, a ‘hole’ or time portal would appear right in the centre of the Delta T antenna - you could walk through the portal from 1980 to 1990. There was an opening that you could look into. It looked like a circular corridor with a light at the other end. The time door would remain as long as Duncan would concentrate on 1990 and 1980.” (8)

I am incredibly skeptical of the story's integrity. It would appear that so much of the 'evidence' presented is based upon pure anecdote, that it is easy to dismiss the whole issue as fictional in a similar way to the time traveller's tale. This 'history' belongs to a whole genre of pseudo-scientific thought which proposes rationales for anomalous behavior (UFO activity, monsters or freak conditions of disappearance such as the Bermuda triangle belong to this, notably rarely seen as the work of God).

These propositions appear to be a particularly strong element of the post Second World War era, with stories turning into legacies as more 'information' is uncovered. Could this be attributed to Cold War paranoia? Recent attention focusing upon the Roswell incident and its alleged footage of an alien autopsy stands testament to these 'legacies' (9). More often than not, the information presented seems so incredulous as to often be dismissed as pure hoax (back to the time traveller again). The very fact that such a genre is perpetuated to such a great extent by societies worldwide perhaps points to some deeper social 'need' to proliferate such myths.

The Time Tunnel (1966-1967)

This spiraling tunnel or vortex merely serves to recall such time travel stories as 'The Time Tunnel' (1966) or 'Time Bandits' (1980), such is the proximity of all the accounts. The problem here I feel, is that Nichols's account in no way attempts to be anything other than a very real and truthful retelling of the events from 1943 to 1983. Due to the nature of the material, the extent of the anomalous behaviour, and obvious preconceived ideas one might have as to the integrity of such claims, it is easy to become sceptical. There is often little effort given to attempting to explore these stories, taken that anomalous, unexplainable behaviour is a regularly condemned to existing as nothing other than sociological myth.

Time Bandits (1981)

Therefore, even with these stories existence, why do people still feel a 'need' to perpetuate them? I feel that this is perhaps concerned with the allure of the unknown (back to Wells again). Time travel stories work on the premise of exploiting this 'grain of truth' syndrome inherent in anecdotes of all types. The fact that time travel tends to speculate upon the future of the race through the vocabulary of the paradox is also no coincidence. Again, it is a reflection of a desire to pay attention to those who claim to be able to foresee the future. The unbelievableness of these issues results as a by-product of conflicting paradoxes.

“Something is said to have presence when it demands that the beholder take it into account, that he takes it seriously - and when the fulfillment of that demand consists simply of being aware of it and, so to speak, in acting accordingly.” (10)

I now wish to return to a couple of issues described by Nichols, which appear to be at the root of all 'time travel'. He describes as necessary a sense of 'aura'. There is also (perhaps as a result of this) experienced, a kind of 'presentness' or 'instantaneousness' which purports to act as a form of 'salvation'. This salvation was seen as an incredibly important issue for early Modernist artists, particularly those influenced by the writings of Helena Blavatsky, who in some respects saw themselves as visionaries, producing aesthetic communications of insight. In striving for this increased interaction of thought with the physical world, many artists turned to the Theosophical movement. Formed in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky, this set out with three aims;

1. To encourage study of the forms of comparative religion, philosophy and science.

2. To form a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity.

3. To investigate and explain laws of nature, and the powers latent in man.

Therefore in embracing these ideas, artists began to see their practice with an increased sense of morality. As these theories began to reach their peak during the spiritualist zeitgeist of the 1890's, they are easily comparable with Wells's writing. The time traveller could be seen to be purely concerned with the third of the Theosophical premises, which leads me to argue that he is comparable with, or a precursor to, artists of this time.

In a sense, the place of magic is also incredibly important in any discussion of this period, yet the view of the traveller as a magician with futuristic insight (Blavatsky herself is also seen as somewhat of a prankster) is not entirely dissimilar to that of artists such as Piet Mondrian or Wassily Kandinsky viewing themselves as on the road to a higher state of consciousness through the production of their work. As part of 'science', geometry was seen to make the distinction between the ordinary and the 'higher' world, and as I have touched upon before with Hinton, the time traveller is keen to stress that time is a dimension which occurs as an extrapolation of the other three. Geometricization is therefore proposed as one way by which to reach a higher state of consciousness.

This leads me to propose that the monolith featured in Stanley Kubrick's '2001', the 1968 monolith of Modernism (11), might in fact be a visual manifestation of these previous ideas. Coupled with this was a particular focus upon the 'internal-ness' of the object. In this I am referring to the object's potential to completely engage the spectator in an 'internal' dialogue of the issues 'inherent' in the object itself. This is demonstrated by the sustained attention the impenetrability of the monolith in '2001' and its resolution in '2010' with astronaut Bowman's infamous phrase 'My God, it's full of stars!'

There is somehow a removal from the contingencies of place and time into a sustained sense of 'presentness'. Therefore, in the context of this discussion, Modernist works (the black 1:4:9 monolith in particular) perhaps aspire to induce Randles' 'Oz Factor'. This is definitely true of the role played by the monolith in Kubrick's film (to which I shall return), the extent of its 'otherness' inducing not only bewilderment but fascination and the desire to obtain a greater degree of 'consciousness' from it.

“In science, satisfaction is a mere by-product of inquiry; in art, inquiry is a mere means for obtaining satisfaction. The difference is held to be neither in process performed nor in satisfaction enjoyed but in attitude maintained. On this view the scientific aim is knowledge, the aesthetic aim satisfaction.” (12)

In his essay 'The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction', Walter Benjamin discusses the purpose and consequences of reproducing works of 'art'. He states that by 'making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence' (13). He terms this uniqueness its 'aura'. In reference to Kubrick's film, this is certainly true of the role of the monolith discovered at the Clavius moonbase. A photograph (a reproduction) is attempted, yet fails, perhaps because alludes to something too unique, a metaphorically unreproduceable visual experience (much like dreams or time travel itself) (14).

In embodying the majority of theories raised in the 1890's and alleged 'real' time travel, the impenetrable monolith might be proposed as a visual manifestation of this. It is perhaps reminiscent of Robert Morris' claim that 'simplicity of shape does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience'.

Footnotes

There are already some promising signs from work by psychologist Dr. Serena Roney-Dougal who has been assessing the actions of the pineal gland, long thought by mystics to be a source of the hidden 'third eye' and which, they suggested, allows spiritual insight. A chemical trigger, via naturally secreted hormones such as serotonin, which is already receiving some attention, may provide a way forward.

Jenny Randles: Time Travel - Fact, Fiction and Possibility, Blandford Books, 1994Ms Randles is most notable in the context of this discussion for writing perhaps one of the most comprehensive accounts of how 'real' time travel comes about (Ref. 1). She also writes for the 'Fortean Times', a regular journal of the anomalous.

Under T.H. Huxley at Imperial College, London, in the mid to late 1880's.

If you tried to measure, for example, the speed of a sub-atomic particle ... then you had to illuminate it with at least one photon of light just to theoretically observe it. Yet this photon will interact with the particle and alter its speed. Thus the observer becomes an integral part of the measuring process. (Ref. 1)

Raffill, 1984 (USA)

Nichols, Preston B: The Montauk Project - Experiments in Time, Sky Books, New York, 1992

One possible meaning of the term 'aura' was explored by early twentieth century seance photography, whereby balls of light were seen to appear around the person, as if capturing their pure 'spirit'. However, these are easily proved as forgeries, produced with simple darkroom trickery (underexposing certain parts of the image whilst processing). For further documentation of this - Channel Four : 'Hidden Hands - Is there anybody out there?' (1995)

Ref. 6

Channel Four : Equinox, The secret history of the Roswell incident (1995)

Fried, Michael: Quoted by Lewis Biggs in 'Minimalism', Tate Gallery Liverpool, 1989

How is this term arrived at? The monolith can be seen as personifying many of the theories inherent in Modernist art, particularly of the Greenbergian nature. For example, it could be argued that it is autonomous and purely concerned with the processes of its own production, although this discussion tends to prove otherwise.

Goodman, Nelson: 'Art and Inquiry' in 'Modern Art and Modernism - A critical anthology'

Edited by Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison, Harper and Row Ltd. 1982Ref. 12, Essay in 'Modern Art and Modernism, A critical anthology'

This is one reason why Clarke's '2010' and '2061' sequels seem so poor in comparison. They are diminishing the initial 'aura', and this is also the reason as to why I have excluded them from the parameters of this discussion.

Chapter Three

“The machine is beneficial, and it will be the machine which, in the end, will completely emancipate man.” (1)

“Simplicity of shape does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience.” (2)

Arthur C. Clarke: The Sentinel of Eternity (1951)

Just as H.G. Wells invited speculation and active engagement from his readers, so Stanley Kubrick also challenges his audience to develop more perceptive film viewing habits. Structured loosely around science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke’s 1950 short story 'The Sentinel', Kubrick's '2001 : A Space Odyssey' (1968) is still generally revered as one of the greatest films ever made (3). Scattered throughout the film is the mysterious presence of the black monolith whose function, in the words of the film's Dr. Floyd "is still a total mystery". It is the notion of this mystery and its relation to the fourth dimension which I intend to speculate upon here (4).

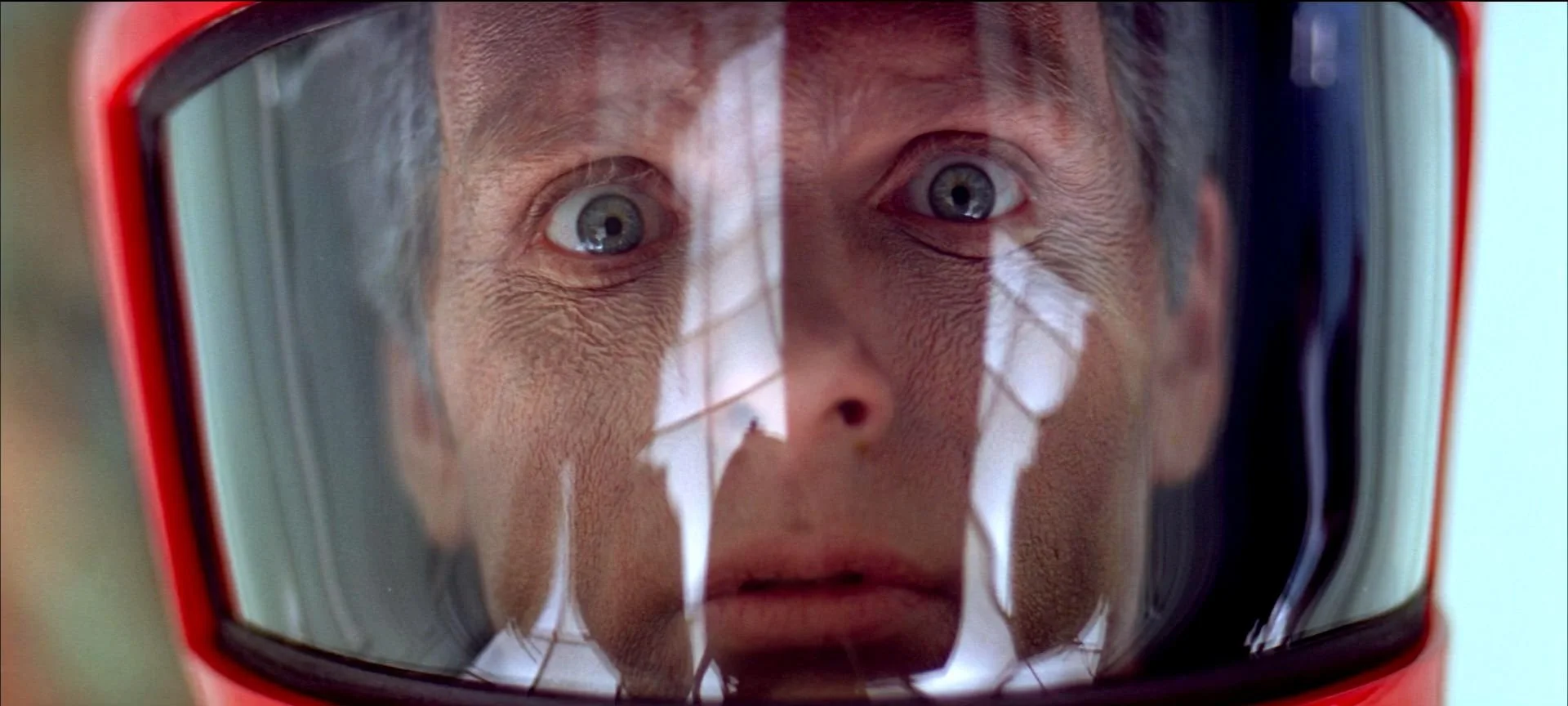

2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick 1968)

Kubrick, often seen as an eccentric director (almost always working in secrecy), renders his themes with a particular style which tends to focus upon the flesh as something weak and fallible. There is a definite aesthetic to all Kubrick films, whether by use of harsh under-lighting or cold, detached visions of graphic violence (the rape scene of 'A Clockwork Orange' (1971) still appears to enrage the British film censors). In doing this, coupled with his choice of subject matter, Kubrick might be seen as a descendent of Wells. '2001' is very similar to 'The Time Machine' in being symptomatic of focusing some degree of widespread attention upon futuristic speculation. Both Kubrick and Wells seem to deviate from an established norm to produce philosophical and psychological works which actually encourage audience speculation.

A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick 1971)

The context of 1968 in which Kubrick released '2001' is also important as it is often seen as a cultural turning point in Western society. The War in Vietnam was still raging (Kubrick returned to this in 1987 with 'Full Metal Jacket'), the student riots in Paris were also at their peak, and various counter cultures were burgeoning. What could be said is that there was in some sense, a substantial challenge to existing sociological norms, corollary to the end of the Nineteenth century. This is interesting in the sense of Kubrick's film containing the monoliths which instigate cultural shock and tremendous social upheaval (they are the protagonists of strange evolutionary 'jumps' - particularly in human consciousness).

Perhaps, in producing the film in this context, Kubrick suggests that the 1968 '2001' fulfills a similar purpose to that of the 1895 'The Time Machine' in physically instigating a change in perceptual behavior. This leads to the proposal that the only real premise of science fiction is to restructure the way in which we might look at the present.

“In the deepest sense, I believe in man’s potential and in his capacity for progress.” (5)

2001: A Space Odyssey, The Monolith Aligns

Kubrick's selection of musical score during '2001' is incredibly interesting (6). When the first three chilling chords of Richard Strauss's 'Thus Spoke Zarathustra' blare out in conjunction with the planetary alignment of Sun, Earth and Moon, Kubrick is immediately setting the tone of the work. Not only the tone but the 'pace'. The start of the film is not the usual quick lead-in of popular Hollywood style, but an attempt at adjusting the speed of the audience's viewing so that every elaborate detail is given some degree of attention (7).

The use of this music in particular also obviously alludes to Nietzsche's discussion of the same title. Therefore by combining this with the image of planetary alignment, Kubrick suggests that the evolutionary transcendence as prescribed by both Nietzsche and Darwin, can perhaps be achieved 'only' at specific moments. Combined with the presence of the monolith, this is enforced 'four' times during the film. The resultant hypothesis could be that evolutionary progression is possibly due to the whim of some 'higher other' force, who creates these situations for its own purposes. Kubrick's primary aim, however, is only to raise and speculate upon these problems, not to answer them.

The theme of human transcendence of a particularly Nietzschean nature is also apt in reference to the increasing contextual role of the Soviet and American space programs. As a metaphor for transcendence itself, the sending of man into space apes the basic premise of Nietzsche's 'Zarathustra', and is indeed, even a device for focusing global attention upon a single event.

For the scenes depicting space travel, Kubrick employs Johann Strauss's 'On the Beautiful Blue Danube' waltz. This is perhaps put to best effect on the Pan Am shuttle to space station one, where we witness a variety of hostesses performing feats of physical agility in the hazardous environment of weightlessness. Wearing 'grip shoes' to anchor themselves to the floor, they appear to give the illusion of a bad ballet, with their bodies rendered somewhat dysfunctional by the lack of gravity. It is notable that females are still performing the same types of activities as those of Wells's time. Whether or not this is because scientific achievement is seen as a particularly masculine enclave is debatable, yet the rather dated concepts of 'domestic woman' are curiously still in place in Kubrick's 2001. Human suppleness, agility, grace and lightness (traditionally 'female' attributes?) have been removed, having now been transferred to the instruments of space travel. It is the machines who are dancing to the waltz, not the somewhat impotent humans.

Yet the most chilling aspect of '2001''s musical score is the use of work by Gyorgy Ligeti in combination with human interaction in the face of the monolith.

“Kubrick stylizes the moment of the birth of human consciousness with the presence of the monolith and ‘musique concrete’ by Gyorgy Ligeti howling from the soundtrack like a collage of all the world’s religious music.” (8)

In using Ligeti's 'howling', the monolith actually screams with this 'birth'. Encountering the monolith is rendered vision-like, as if coming into contact with some form of transcended religious spirit, and it is true to suggest that the story is treated as particularly reminiscent of 'biblical'. This rendering of some form of spirit relates back to the time traveller's dinner party as being no more than a seance, the result of which is a hoax.

Many late Nineteenth century photographers (themselves comparable to magicians in the sense of alchemists, transforming base matter into 'gold') attempted to convince their audience that they could in some way record a person's (usually a mystic's) 'aura', thus 'proving' the existence of a transcended spirit. This was incredibly popular at the time, yet later obviously proven to simply be the result of darkroom trickery.

The film, after the initial sequence introducing the Nietzschean theme in conjunction with planetary alignment, begins with the 'Dawn of Man' sequence. This is the first of four separate parts of the film which combine to eventually produce the transcended 'Starchild'. The 'Dawn of Man' sequence concerns two groups of apes, barely managing to exist somewhere on the African plains approximately four million years ago. In using long, lingering shots of the African desert landscape, Kubrick is still slowing down the pace of the audience's viewing, so that when there is a scene involving 'fast' action (such as an ape being attacked) it is rendered with a strange unnerving 'coldness'. At the time where we join the apes, they seem on the brink of extinction, and are dominated by, and live in fear of, faster animals such as the predatorial leopard.

2001: A Space Odyssey, Moonwatcher

One morning (literally the 'dawn' of man), they awake to find a huge inert black monolith standing at the entrance to their cave. This signals what could be termed 'the birth of human intelligence'. Initially tentative, one ape (whom Clarke names 'Moonwatcher') appears to 'learn' from the 'slab', and has the idea of using a bone as a weapon. He has now begun the transcendence from ape to man. It is as if the monolith has become like a Biblical tablet of knowledge, instructing the followers of its teachings in how to progress. This sequence is rendered to dramatic effect again by using Strauss's Zarathustra and the recurring mental image of planetary alignment.

“The cosmic midwife of this transmogrification is a mysterious black monolith that appears at a crucial point in the ape’s evolution.” (9)

It is also noticeable that there has been no dialogue until this point (aside from the apes screaming), and this continues for most of the film's first hour, making the 'howling' of the monolith all the more powerful. Having achieved this imminent breakthrough in human intelligence, the pedagogical monolith disappears as mysteriously as it appeared. It is seen that the apes (now able to hunt for meat) appear much stronger than before, and they are also, for the first time in the film, standing. Moonwatcher has obviously imparted his newly learnt skill to his peers, according to the Darwinian methods of adaptive success and they now seem poised to develop into early human civilization.

“A new animal was abroad on the planet, spreading slowly out from the African heartland.” (10)

There then follows Kubrick's famous jump-cut from a bone hurtled into the air by Moonwatcher during a fit of violent ecstasy to a descending rocket or satellite (it could also easily be a bomb) orbiting the Earth in the year 2001. In the change from one frame to another, Kubrick has bypassed the entire history of human civilization over the previous four million years, and demonstrates that all basic instruments are derived from the initial use of the bone. It is a jump from one twilight moment to another. In the first, humankind (or its early form) almost dies from a lack of science, whereas in 2001, the instruments which initially saved us now seem poised to destroy everything.

It is as if science is seen as some form of paradoxical hindrance, in one sense aiding technological evolution, yet conversely, having the power to destroy it. Kubrick, as with Wells, suggests that there is a danger in the abuse of scientific knowledge. From the prehistoric world of absolute chaos, the world of the future is now absolutely 'managed'. Science has created its own order. This seemed a far off thought even in 1968, yet now in 1995 this supposed prospect seems fairly natural. Therefore the satirical prophecy of 2001 is somewhat blunted by its own fulfilment. In watching '2001' today, it is obvious to see how this has happened, particularly with regard to the increased role of communications technology, and the possible dehumanizing effects which it has upon its users (as demonstrated by the strained telephone conversation between Floyd and his daughter).

“By 2001 everything we have now will be operating somewhere. And it will all be obsolete.” (11)

Returning to the events following the 'jump-cut', this is where we are first introduced to the figure of Dr. Heywood Floyd. Surrounded by the dancing (by barely waltzing) hostesses, Floyd's behavior aboard the Pan Am shuttle points to many aspects of what perhaps Kubrick believes has happened (in relation to the use of scientific knowledge) since the initial use of the bone. Floyd lies asleep in an empty shuttle, his singularity emphasizing the importance of his mission. What is essential to realize is that in essence, Floyd merely replicates the actions of the original ape. He is on his way to a lunar base, he is literally the modern Moonwatcher.

2001: A Space Odyssey, The Floating Pen

Whilst asleep in the shuttle (it is apparent that Moonwatcher's eyes were wide open, whereas Floyd's appear tired and jet-lagged), his 'atomic Parker pen' floats by his left hand. In re-enacting the role as the bone carrier, the bone itself has been replaced by the pen, the instrument of written language. Instead of brute violence conducted physically, it would appear that language is now the primary tool of argument. As the carrier of this knowledge, his authority is ironically asserted in the face of the hostesses stumbling. In this, Kubrick is mirroring the growing power of the written word in the twentieth century, and the authority which documents purport to have (i.e. Chamberlain's famous dictum 'In my hand I have a piece of paper'). Annette Michelson suggests that weightlessness creates a difficulty in actually achieving purposeful activity (12), and this is certainly true of this scene.

As the harbinger of supposed knowledge, and in the position of authority which results from it, the notion of Nietzsche's 'herd' is hinted at. In a sense, there is a basic, almost carnal desire to be 'led'. This is reinforced by the fawning Floyd receives after he delivers his speech on the Clavius moonbase. However, preceding this, Floyd has an encounter with a group of Soviet scientists, whereby the use of language clearly demonstrates the difference between the past and future worlds. Whereas Moonwatcher was only too quick to tell his peers of his new information, Floyd, under duress to impart his knowledge, merely skates round the issues sought by the Soviet questioning. His secrecy surrounds a cover story concerning an epidemic on the Clavius moonbase.

The Soviets, merely concerned that it might spread to their base, demand the facts from the reticent Floyd, who denies them any useful answer. This is a rather literal reflection of the Cold War period, and pessimistic in showing no signs that this could be resolved. Of course, this is completely the opposite to what actually happened in the late eighties and early nineties. It is subsequently revealed that the cover story is to conceal the fact that a second monolith has been uncovered on the Moon, having been buried there approximately four million years ago. It is as if the 'aura' of the monolith (in this case it literally has a large magnetic field surrounding it, which is the reason for its discovery) is instigating both secrecy and the desire for exploration. The origins of the monolith are again, a complete mystery.

“If alien races have ever visited Earth in the remote past and left artifacts for man to discover in the future, they probably chose the arid, airless lunar vacuum, where no deterioration would take place and an object could exist for millennia.” (13)

As with the group of apes, the humans investigating the monolith approach it tentatively, it is, after all, the first evidence to their knowledge of intelligent life off the Earth (which is not part of the 'spiritual' genre of phenomena - this is hard evidence). Through a gloved hand, Floyd touches the monolith with complete bewilderment, then proceeds to join the other scientists for a bizarre group photograph with the monolith. As the photographer is preparing the shot, a deafening blast of radio energy is emitted from the monolith, causing the scientists to try to cover their ears with their hands (of course, impossible due to their space helmets).

As if placed as a marker by the other intelligence, to signal to them that humans have reached this stage in their evolution, the monolith is particularly relevant in the context of the apparent four million years of technological progression, as it itself has not had to change at all. As if the second part of some cosmic puzzle, showing no signs of having any connection with technology at all (mirroring Wells's Eloi and Morlocks), therefore questioning our desire for tools in the first place.

The black monolith next appears after the sequence of events concerning the space ship Discovery's mission to Jupiter. This third instalment of the story is perhaps the most memorable of the entire film. It is particularly noteworthy in the context of the previous discussion as to the futuristic relationship between man and science, as it depicts the most human of all the film's characters, the on-board HAL computer (14). Due to the Clavius monolith's violent radio emission having been targeted at Jupiter, it is subsequently decided to send a team there to investigate. In brief, after emphasizing the daily monotony of the two dehumanized astronauts, David Bowman and Frank Poole, Kubrick then depicts HAL's paranoid breakdown (due to conflicting orders) whereby he kills Poole and the hibernating members of the crew, before Bowman finally manages to disable him by shutting off his higher brain functions.

“HAL fulfills the paradoxical dynamics of the telephone. Seeming to keep everyone in touch, yet finally cutting everybody off.” (15)

Kubrick had previously emphasized the impact that increasing technology has had upon humans (Floyd is about as dehumanized as possible) yet here the roles are reversed, it is questioned as to man's impact upon technology. Machines are almost treated as autonomous entities. In the way in which they communicate with humans it could be said that they are in fact more than human, a flawless, unmistaken 'version' of human. Indeed, it is only when this machine in particular (HAL) begins to show signs of human emotion, that the paranoid breakdown begins to happen. HAL is the futuristic version of Victor Frankenstein's monster (ironically Mary Shelley's novel (16) is often hailed as the first ever work of science fiction).

I feel that his weaknesses stem from the initial BBC12 interview conducted with the ship whereby the presenter tends to flatter HAL about his perfect operational record. He is merely reiterating the absolute faith installed in him by his working companions. If there is no HAL, there is no mission. From this point onwards, HAL begins to notice and play upon the emotional discrepancies between him and the crew, eventually leading him to cause the AE35 (satellite dish) unit to fail - the one piece of equipment vital for the most basic of actions - communication. These events personify the way in which the film tends to reflect the growing anxiety as to the increased role of technology (again parallel with Wells). Has science of the late Nineteenth century genre been replaced by technology?

In an excellent essay for 'Screen' magazine (17), Ellis Hanson focuses upon a particular aspect of HAL, his voice, and how it might therefore be proposed that HAL is not asexual as with all other machines, but in fact, homosexual. It is true to say that there is a certain destabilizingly erotic appeal to the aesthetics of machines (think of the passion we hold for certain models of car). The time machine itself has been called 'science fiction's sexy little sports car' (18). Hanson suggests that this sexuality is emphasized through HAL's voice (played by Douglas Rain). Aside from the other homosexual connotations of all the crew inevitably being male, HAL's 'queer' tones are strengthened in the face of so much asexuality with Bowman and Poole. In sociological terms, homosexuality is often viewed as the ghost in the machine (Hanson implies this by exploring fears of illicit pleasure versus sexual anxiety), ultimately causing the collapse of a well-established 'norm' which refuses to acknowledge such behavior. This could perhaps be reflective of many emerging cultures of the sixties.

“There is a sexiness to beautiful machines ... we are almost in a sort of biological machine society already.” (19)

In continuation of the debate concerning the time machine itself, it would seem that in creating such apparently liberating technology, what is actually happening is a debasement and undermining of elements of the natural world (humans included). HAL's behavior reflects and confirms the diminished role which we tend to play in attempting to coexist with such rapid and accurate machinery.

After all, it is the machine which ultimately allows the time traveller to live up to his name, just as it is the equipment of spaceflight which allows us to fulfill Kubrick's 'evolutionary jumps'. Yet what is stressed is that these creations are ultimately fallible, HAL in terms of machines attempting to mimic the brain, and the time machine in terms of perceptual anomalies. In this sense, Kubrick merely expands upon Wells's initial speculations as to the integrity and purposefulness of having such utilities in the first place.

2001: A Space Odyssey, The Stargate