Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast

A contemporary three graces

Year Two Dissertation, Kingston University Department of Art History, 1994

Programming Note: For my second year’s thesis work, I explored the notion of tying together the principles and values of Antonio Canova’s 3 Graces with the contemporary practice of Sam Taylor-Wood, Sarah Lucas and Anya Gallaccio. this project allowed me to interview numerous primary sources (including Michael Archer, Sam Taylor-Wood and Sarah Kent), as well as learn how to handle a large volume of material and distill it down into a meaningful, manageable, clear form for readers.

I also held a seminar in the main lecture theater at Kingston University, which was really the first time I had publicly spoken or presented anything of substance during my degree.

None of this project has ever existed digitally, most of it being produced on an old-fashioned typewriter and hammered out by hand. This written work was also the first time I’d made a physical object out of anything I’d written, and I worked closely with the legal bookbinding firm R.G. Scales who were located in Inner Template near the Embankment in London to bring this project to life. This project allowed me to learn how to produce a large-scale piece of writing, and those learnings ended up defining a lot of the following year’s Time Travel thesis.

“Cherry soda, coco pop, it’s so sweet your teeth will rot.”

Huggy Bear: 'Snow White, Rose Red'

Preface

“In a relationship of violence there is joy and beauty and, conversely, beauty and enjoyment are also violence.”

Stella Santacatterina: 'Karsten Schubert' Tema Celeste (January 1992)

This investigation is primarily based upon the somewhat simplistic premise of questioning the possibility and relevance of using the traditional, familiar and iconic subject matter of art history (and indeed, also mythology) in order to look at contemporary practice in a fresh and perhaps more interesting light.With this in mind, I have chosen to base my exploration around the iconic, mythological subject of 'The Three Graces'. Depicted by artists from Raphael to Rubens, it is perhaps arguably most famously, or in recent months, infamously, Antonio Canova's 1815 sculptural interpretation of the Graces which is perhaps one of the most familiar portrayals of this subject, and indeed, of the Classical era itself.

The Graces represent the ideals strived for in Classicism. Perhaps this is the reason for their survival. To begin with, the classical period viewed Ancient Greece as somewhat of a pinnacle of social perfection, a Utopian state which was to be aspired to through the highbrow vocabulary of 'art'. It was believed that art stood for a social state of affairs, therefore, it would naturally follow that one of the greatest civilizations would in turn produce the greatest art. Yet with the dawn of the Victorian era. this harking back to an idealized state was then corrupted through the use of new mass production techniques, leading perhaps to our assumptions today of work from that era becoming devalued and even 'kitsch'.

Marble Statue Group of the Three Graces

Second Century A.D., Roman, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This obviously begs the question, why have the Graces survived this assumptive ‘lowbrow’ corruption? I would suggest that, because of its subject matter having already been interpreted as a traditional cultural 'force' (there has always been a place for mythology in society) throughout art history, coupled with the more literal element of the fact that it is made from solid and durable marble, they have therefore become icons of Utopian perfection. They are personifications of one of the fundamental qualities of art, that of beauty.

The Victorian debasement of Classicism is mirrored in recent media attention concerning the supposed sale and subsequent non-sale of the work between London's Victoria and Albert museum and the John Paul Getty museum inCalifornia. This debate has forced a somewhat contemporary and surprisingly public reappraisal of the piece's inherent 'value' and importance as an artwork. Yet I wish to stress from the outset that my aims are not to tackle any great issues surrounding discussion of this nature pertaining to the work, as I would suggest that it would be perhaps more interesting to engage in an actual 'historical and contemporary' re-analysis of the subject, rather than any exploration of the merits of inter-museum financial transactions.

The Three Graces

Peter Paul Rubens (1630-1635), Museo del Prado, Madrid

Returning to the Graces themselves, they were traditionally (and I should make clear that there is a plethora of differing accounts) the daughters of Zeus and his then third wife, the sea nymph Eurynome. As with most of the characters from Greek mythology, they represented abstract ideas but in human form (presumably so that they could be related to lived human experience), therefore often lying in limbo between the natural and the human. They therefore obviously related to aspects of human aspiration, almost transcending any form of artistic interpretation (perhaps this is why the hybridian Classical depiction is particularly well suited to this idealization of form). As elements of the natural world (and of course, this relates to the Dionysian equation of woman with nature and chaos, perversely somewhat in opposition to the Appollonian restraints imposed by Classical techniques), they were spirits of vegetation, who lived on Olympus and were assistants to Athena.

Often depicted nude and in close embrace, their names were Aglaia, Thalia and Euphrosyne. Collectively personifications of grace, loveliness and charm, they each also had their own particularly personal attributes. Aglaia was known as the brilliant', she who represented splendor and warmth of character. Thalia came to symbolize a personification of abundance or 'she who brought flowers', and lastly Euphrosyne, who exemplified the qualities of mirth and gladness, in other words ‘she who rejoices the heart’. (F. Guirand: ‘The New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology’ Hamlyn 1959)

The Three Graces

Antonio Canova

The artistic origin of the Graces appears to be unclear, yet a plausible explanation, as described by Kenneth Clark (‘The Nude’ John Murray 1956), suggests that they are possibly derived from a row of Greek dancers, with the customary and traditional posing of the arms on each other's shoulders, front to back (still an aspect common in Greek dancing). In dark's account, sometime around the fourth century A.D., an anonymous artisan removed a number of side dancers to leave the familiar, close group of three which we now associate with the Graces. This, of course, lends itself again to the ideas of the Classical, sculptural interpretation, as, with three differing viewpoints, even though it was a 'sculpture' (and supposedly made in the round), the viewer was hardly required to walk around the piece as is normally the case.

I am also intrigued by the use of the number three in conjunction with this subject matter. I feel that there are a number of different reasons as to why there are three Graces, yet within the contemporary context of this discussion. I feel as if it is hard to look at a depiction of three nude women in close embrace without it being read through a sexual vocabulary.

However, and in spite of this, I think it is problematic to justifiably approach the Graces in this Post-Feminist manner, partly due to their art historical 'weight' and of course, because they date from a period before documented debate of this nature. These debates, formed in the 1970's as a result of the changing attitudes towards art caused by Modernism in the 1960's, form the backdrop to the contemporary debates which I wish to explore.

The Three Graces

The Louvre, Paris

Throughout art history, the Graces have become familiar and popular (they are now publicly owned), signifiers of beauty and purity, everything art is stereotypically supposed to be, yet when transposed into starting criteria for re-analyzing contemporary practice, I feel as if there is a particularly and often peculiarly apparent correlation between the legacy of the Graces and the work of specific young artists.

Therefore, my somewhat speculative exploration is based upon a potential marrying of two seemingly disparate historical elements. I feel certain that there are many differing perspectives as to whom each of the contemporaryGraces could be (particularly with regard to other artistic practices, as I intend to discuss later) yet my criteria for 'selecting' the correlating artists will be that of an almost literal transposition. The artists which I have chosen to discuss are in some ways, perversely similar to the Graces.

They are all young, female and London based, and in my opinion, their work embodies the individual respective qualities of each of the Graces. Therefore, in utilizing these parameters for my discussion, I have chosen to discuss the practice of Sam Taylor-Wood, Anya Gallaccio and Sarah Lucas.

Les Trois Graces

Jean Honoré Fragonard (1768-1773)

I intend to demonstrate how each of the artist's works can be re-analyzed in the light of their common theme of the three Graces, yet I feel that it is also perhaps important to be conscious of the fact that I am only intending to use the historical subject matter of the Graces themselves as a springboard for analyzing and exploring the questions raised in looking at these contemporary works.

I have already touched upon the debates which arose in the 1970's (in this I mean that there was a re-evaluation of beliefs upheld throughout art history, in the light of the vocabulary of those excluded from history), which not only affected artistic practice but also society as a whole. In reference to this, I feel as if it should also be possible to establish a framework of debate which would allow for a contemporary version or equivalent of the 'parents' of the Graces, Zeus and Eurynome, to somehow compliment the historical lineage of my investigation. Yet this seems to be a problematic exercise from the outset. Figures which at first appear to be referential or have some 'spiritual ancestry' are difficult to establish as solid 'parental' references. It is often the case that the younger, contemporary artists hardly ever appear to be influenced by them or they see them as unrelated to their own working processes. However, the so-called 'previous generation' of parental predecessors as I will term them, including artists such as Paul McCarthy, Gilbert and George, Helen Chadwick or Carolee Schneeman, are firmly grounded within the debates of the seventies, particularly with the reclamation of the body as a site for works, and it is this assumption which leads to the highly influential force of Feminism upon the interpretations of contemporary works.

The Three Graces

Raphael (1504–1505)

As one of the major cultural forces of the 1970's, it changed the fundamental nature of art in that it significantly altered the perception or reading of the image. The female body (stereotypically equated with 'art') was reclaimed after centuries of male corruption (most notably through art education and the proliferation through art of demeaning stereotypes) to provide a new agenda for looking at the entire practice. This also opened up the debates of culture for so-called 'other' groups (in effect, any group which wasn't white, heterosexual, male, and middle class) thus facilitating the birth of the age of political correctness in which we now live. However, I feel that it is perhaps problematic, due to this cultural upheaval (the widening acceptance of the groups collectively referred to as 'other', which of course is a very subjective term) of the 1970's, to look at a female artist's work without the issue of Feminism arising, therefore, through my very biological make-up as a male, my reading of issues pertaining to the debates surrounding the shifts in cultural power within the contemporary works may prove to be a little unconsciously subjective.

This exploration is split into four main sections, the first three being individual explorations of each of the artists practices (in relation to the historical duality between the debates raised through the work and those of mythology and recent cultural upheavals), and the fourth and final one an attempt to draw together some of the more interesting questions raised during the course of my discussion.

Sam Taylor-Wood: Delicious Matinee Violence

“My work is about defining yourself as a sexual being and being proud of it. What I do is about taking pleasure in being sexual. It’s as simple, and complicated as that.”

Sam Taylor-Wood: Misquoted in 'British Art Special' The Face, No.68 (May 1994)

To begin with, this discussion is born out of the notion that this artist's work is, in a very perverse sense, related to the first of the Graces, Aglaia, ’she who represented a brilliant splendor’. This I have chosen to analyze in terms of the troublesome images prevalent in Sam Taylor-Wood's work, and to discuss how her work embraces the mythological quality of a sumptuous splendor through the vocabulary of sexual grandeur, pride and decadence. Her splendor is that of a debased sexuality, coupled with a perverse reveling in the darker sides of the sexual self-image.

Sam Taylor-Wood’s work is primarily a subversion, inversion and undermining of certain dominant and widely held social beliefs through the use of the somewhat uncontrollable yet universal languages of gender and sexuality.It is also perhaps a happy but also conscious accident that she chooses to call herself Sam instead of Samantha, an obvious androgenously reflective play upon the gender issues within her work. Yet in re-appraising and questioning the existing debates of gender, art history (particularly the female's relation to art history, reductively as subject or object and rarely as protagonist) and the responsibility of the artist for creating problematic images, she is working very much within a certain designated, highbrow and almost elitist social framework set aside for such ‘artistic’ activity. Therefore, to make the work perhaps operate more within the public arena, she metamorphosizes it into a fluid, accessible, and ever moving state, becoming a constantly moving target, behind which she is then able to avoid the metaphorical bullets of a supposedly dominant cultural force (be it male hegemony, stereotyping or art history itself) in order to manipulate the boundaries of the ever decreasing social frameworks for artistic practice.

Therefore, her work's relationship with the 'audience' becomes increasingly important, and it is this aspect which demonstrates the fluidity of the work.

Fuck Suck Spank Wank

Sam Taylor-Wood (1993)

She plays upon many different audiences, be it returning the viewer's gaze from behind dark sunglasses in the intimate context of Fuck Suck Spank Wank (1993) or testing reactions to her work within the wider sphere of society by provocatively fly posting her piece Svastika (1993) in the racially motivated melting pot of Brick Lane in London's East End. The audience are confronted, questioned, and forced to reconsider dominant, widely held beliefs through an artistic language which often deliberately provokes conscious misreadings.

This is due to the fact that the images themselves, which are primarily photographic (and supposedly therefore 'believable'), as opposed to either sculptural or painterly are very much concerned with a specific ‘layering’ of meaning, or as is often the case, a method of image manipulation and construction akin to Seventeenth century Dutch 'Vanitas' still life painting. This methodology almost teases a response out of the viewer, and with the assumption of art history that the viewer is predominantly male, the metaphorical subtext to this teasing brings to mind the notion of a torturing of the Greek God Priapus (the God of the phallic erection). This casual teasing, arrogant in its over-construction, flies in the face of the historical notions of passive female and dominant male by using the language of a debased, androgenous sexuality (negating male/female boundaries) mixed with a subtle violence underlying common stereotypical beliefs.

Spanker's Hill (1994) is a small photographic work which deals with precisely these debates. The scene depicts an unlit road in the countryside, along which is speeding a car, and crouched, about to meet a violent death, is the artist, unflinching and dressed as a rabbit. As I have already mentioned, Taylor-Wood's work indulges in a sumptuous ‘layering’ of meaning, therefore, in order to perhaps unravel such a complex image, I intend to briefly take into account the individually disparate elements which produce the eventual hybrid-like result.

An obvious starting point is with the image of the artist herself. Aside from the rather simplistic reductions of women into bunnies as with 'Playboy' magazine, rabbits are generally regarded to be incredibly virile animals. We need only think of the phrase 'they were at it like rabbits' to be reminded of this. Yet placed within the context of it being a disguise for the artist and the aspect of her imminently becoming 'roadkill', the originally sexual mood then becomes one of extreme impotence. The disguise is used as a front, behind which the artist can hide and arrogantly stare back at the oncoming force. A possible metaphor for her methods of working? It is this oncoming force which seems to be under scrutiny from the artist, in itself a subversion of what we actually see (the artist is in the end the one in control).

Cars are widely recognized as closely guarded objects prevalent within a particularly masculine enclave (think of programs such as ‘Top Gear’) and more specifically, as a result of this, metaphors for the phallus itself. It represents a particular set of male social values (indeed, a particular type of male), yet by using the notion of reducing a man's libido down to the size and model of his car, this subverts the idea that males have indulged in for centuries in the art world, reducing females down to their breasts and genitalia. The most memorable example of this being Magritte's ‘The Rape’ of 1934.

In spite of all this, my own view is that the image has very strong parallel relations with the much publicized case of the American couple Lorena and John Wayne Bobbitt. It concerned one John Wayne Bobbitt (his name obviously apt for Feminist critique) who, whilst sleeping, had his penis cut off by his disturbed wife Lorena, who then proceeded to drive off into the night, still clutching the phallus. When it later horrifically dawned upon her what she was holding in her hand, she was so shocked and emotionally distressed that she proceeded to throw the bloody penis out of the car window. The police were later able to recover the penis, whereby it was then frozen and later sewn back onto John Wayne Babbitt.

Taylor-Wood's photograph can be seen as a subtle re-interpretation of this extremely unsubtle case. It has most of the literal elements such as the time, the geography, the car, and the use of delayed photographic exposure (thus creating the illusion of speed) to produce a phallus shaped streak of red. There are also the more metaphorical references, such as the questioning of how to react to a dominant cultural force such as the penis. The artist, instead of using such violent measures as Lorena Bobbitt acts in a similar way by blankly, arrogantly and defiantly staring back at whatever she sees as the 'aggressor' (male dominated art history or the stereotypically moronic British male) in a similar way in which Manet painted Olympia in 1863, returning the gaze of the dominant cultural force of that time.

This idea of the gaze (Lynda Nead: ‘The Female Nude - Art, Obscenity and Sexuality’ Routledge 1992) is requestioned in perhaps Taylor-Wood's best known work, 'Fuck Suck Spank Wank' (1993), shown as part of the Wonderful Life exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in London.

The image concerns itself with a whitewashed photographic studio (complete with detritus) in which stands the artist, wearing dark sunglasses, trousers down around her ankles and a T-shirt bearing the slogan of the title. Obtained from a gay activist group dedicated to ‘outing’ prominant public figures, the T-shirt somehow forces every other element of the piece to be concerned with this notion of concealed sexuality.

The pose is obviously of a Classical nature (perhaps a relation to the theme of the Graces), which perversely brings into question notions of concealed homosexuality of some of the great artists throughout history. Does or would our reading of their work change now that we know that Leonardo and Michelangelo were gay? Should Clement Greenberg's ‘All that matters is results’ hold true of the Renaissance artists in late twentieth century re-evaluation? The piece also reflects the Greenbergian reference, being reminiscent of Hans Namuth's well known photographs of Modernist artists in their studios (Pollock's images in particular come in for close scrutiny in another work by Taylor-Wood entitled ‘Gestures towards Action Painting’ of 1992).

This investigation of disguises, concealment and camouflage is an ongoing concern for Taylor-Wood. Her work acts as a deployed aesthetic screen behind which she can remain largely anonymous and present the viewer with personae, be it herself or others. This has an obvious correlation with her use of the dark sunglasses, returning the gaze of the audience, although we are unsure even of that.

There is a very real sense of enjoyment on her part in what she does, playing with the audience's relationships with her images. For example, there is a real 'pride' in the fact that she's been caught with her trousers down (another reference to 'outing'), the pose is a defiant one, a 'come on then' stance which revels in her own self-splendor. Yet this is in opposition to the mysterious cabbage to her left, which, as the artist has said, acts purely as an aesthetic device, employed because the picture needed another element, and it was to hand (it was found in the fridge it now sits upon).

This element provokes a conscious, playful misreading, in which the audience are forced to consider it in terms of the common vocabulary of the image(namely sexuality). This reflects, I feel, the stereotypical equation of women with elements of the natural world, fruit often signifying female genitalia, so in fact even though it was employed purely aesthetically, it still fits within the framework of debate which surrounds the work.

In Slut (1994) the audience is confronted with the aftermath of such splendorous posturing. It again depicts the artist (yet it is still not a self-portrait but a reflection of persona), her neck having been ravaged and scarred with love bites. In contrast to Fuck Suck Spank Wank this piece also functions in a particularly real and social sense, the artist having to live with the markings of the work until they faded away.

“I had a poloneck jumper on, and I forgot about it, it was hot, and I just took my jumper off. Everyone was staring and I had to say things like ‘This? It’s art you know’”

Sam Taylor-Wood: In conversation with Matthew Shadbolt, Bar Italia, Frith Street, London (2/9/1994)

Paradoxically reproduced in ‘The Face’ magazine, Slut deals with a perverse, school playground style of performance recording. Even though the lovebites were produced non-passionately, they are seen as a very brash and public declaration of having recently enjoyed wild and amazing sex.

As the subject of this 'ravaging' is again the artist, one can assume that it could be read in a similar fashion to Spanker's Hill, the artist becoming a target for some dominant, stereotypical force to rail against. Here the artist hides behind another erotic disguise, heavy layers of make-up.

I'm not sure if the 'ravager' would be art history as with her other images, I feel that this particular one is directed perhaps more towards a more chauvinistic male enclave, the 'lad' culture so prevalent in proliferating stereotypes of women, one example being the typical 'Essex' or 'Page Three' girl. This piece goes one step beyond Fuck Suck Spank Wank in that it is the consequential aftermath of an encounter, yet the pride and arrogance remain a constant, the artist hiding behind a disguise of sexual stereotyping in order to attack the very forces which proliferate these stereotypes.

This is the very idea that would appear to be the important functioning thing for Sam Taylor-Wood. The constant questioning of her role and responsibility as an artist, and particularly a female one, in relation to the dominant cultural, political and stereotypical forces of society. To do this, she has to be constantly moving, like a target, and employs devices behind which she can hide and shift responsibility and blame for the images which she makes. Perversely rich in art historical references, they also attempt a re-evaluation of the art world itself. Yet to return to the common springboard theme of Greek mythology and the Graces, Taylor-Wood, through her production of these complex and layered images, attempts a teasing of what is traditionally assumed to be the 'male art audience'.

Although I feel that the issues presented are not truly reflective of Feminist debate in a 'me viewer you object' kind of way, it’s a play upon the art world's hegemony, but the important thing seems to be that the images are both humorous and also present perversely serious critique of socio-sexual activity. She does this by employing such methods as theatre, artifice, sex, and camouflage. I feel that this is how she comes to produce images which revel in the splendor of the perversity of the human condition.

Anya Gallaccio: Perpetual Transformations Over Time and Space

“I see my works as being a performance and a collaboration. There is an unpredictability in the materials and collaborations I get involved in. Making a piece of work becomes about chance - not just imposing will upon something but acknowledging its inherent qualities.”

Anya Gallaccio: In conversation with Kim Sweet, 'Anya Gallaccio', ICA London (1992)

Of the three contemporary artists that I have chosen to discuss, Anya Gallaccio's work is that which perhaps relates most closely to its corresponding Grace. I feel that the work has an almost direct and literal correlation to the central Grace, Thalia, 'she who brought flowers' or 'she who represents abundance'. The subsequent roles of abundance and also of flowers in Gallaccio's work appear to be of primary importance to her practice.

Traditionally and simplistically seen as symbols of love, femininity and sexuality (indeed 'beauty' in general), flowers are transformed by Gallaccio into metaphors for social and bodily situations, the works concerned with a transformation of decayed significance. That is not to say that her work is exclusively flower based. This questioning and investigation into the decay and putrefaction of natural and man-made materials has also come to include oranges, chocolate, photographs and bodily fluids.

The very specific transformation of transient materials from one thing over a period of time into another is central to Gallaccio's practice. The process becomes the work rather than a comparison of two elements in a scientific and experimental 'before and after' fashion. In a sense, the viewer is only able to see one fragmented part of the piece at any one time (as with a photographic record), as the works she makes are very much concerned with being transformational and time-based, therefore having a closer relation to practices of the sixties and seventies such as performance art and the ‘living art’ of Kounellis, rather than what is generally termed as static ‘sculpture’. There are also particularly close links with the period of Abstract Expressionism, which I intend to discuss later.

Photographic recordings of the work therefore often fall short in actually representing the works ‘correctly’. In relation to this, her work can be seen as being particularly transient itself (as opposed to the sculptural tradition of lasting memorials, so in this sense it is undermining the very notion of permanence upheld within the art world), with the works destroying themselves over a relatively short space of time, and the viewer only being able to interact with the piece at one unique moment during the work's life.

This in turn poses interesting questions for gallery directors and collectors, individual works having to be remade every time that they're shown, even then(as with similar performance or video work) only having a limited 'existence'. This becomes reminiscent of the so-called 'telephone art' of the 1960's and 1970's conceptualists, the rights to the realization of the idea being the salable item, as opposed to anything actually materialistic.

“Making art that is so vulnerable to change (art, indeed, whose effects are determined by change), Gallaccio stages a series of reproofs to one of the traditional ambitions of the artist; the ambition for permanence.”

Andrew Graham-Dixon: 'Broken English' Serpentine Gallery Exhibition Catalogue Essay (1991)

Red on Green (1992), shown in the regency of the ICA's Nash Room is typical of Gallaccio's approach. Impressive in scale and physical realization, metamorphosizing itself over time, and specifically concerned with the transient process of making itself, it consisted of an installation of 10.000 red roses, the heads of which had been individually removed by the artist.

Red On Green

Anya Gallaccio (Institute of Contemporary Art, London 1992)

The red petals lay on the remaining green bed of the stalks, hence the name of the piece. The domestic and chorish, physical process of removing the heads from the flowers is very similar to the child-like daydream activity of pulling petals from daisies in a 'he loves me, he loves me not' fashion, and this seems to be important metaphorically within the work. I particularly feel that when talking about a piece which is made of flowers. it is difficult to escape cliched connotations of romance, therefore I do feel that the title suggests another set of criteria through which to re-look at the work in a different context.

Aside from the formalistic, aesthetic and titled relations to Rothko's paintings, the piece is also very painterly in approach, like a huge canvas stretched out on the floor as in Namuth's photographs of Jackson Pollock. The artist describes this ‘floor’ (as opposed to floral) aspect of the work as an attempt to make a 'bed of roses' (another obvious romantic cliche, but also with the two layers of flowers becoming like sheets), something which the viewer might want to lie in, yet through the essential element of the decaying process, there is definitely a more sinister undercurrent to the work.

“The piece will have an initial glowing vibrancy, but then the petals will turn brown, like scabs, wound-like dried scabs.”

Anya Gallaccio: Quoted in 'Sweet Home' Exhibition Catalogue Essay by Susan Daniel, Oriel Mostyn Gallery, Gwynedd (1992)

Instead of being concerned with the somewhat cliched connotations of flowers I feel it is much more of an investigation or critique of relationships in general, and their inherent emotional qualities. Roses are traditionally accepted as the signifiers of affairs of the heart ('my love is like a red red rose') and the fact that they are red, a warm color, is also very important. The piece plays upon a system of dualities, having two levels(both metaphoric and aesthetic), the top, surface level relating to the somewhat surface passion and emotion of a relationship (the public 'front'), the stalks underneath showing a thorny, darker side. Green, the traditional color of jealousy and envy can be seen as representing all that underlies a relationship. There is a notion of subtle violence in this somewhat poetic piece (also with the fact that the heads have been pulled off, as if one is metaphorically 'losing your head'), be it emotionally or mentally, which seems to be in question here. The critique being offered up here through the decay of the work, would appear to demonstrate that the universal notion of ‘romance’ has an attractive, appealing and radiant surface or outward appearance, yet underneath, lying behind the social fabric, lies a violent, impure and jealous underbelly which becomes more visible as the surface rots away like a dried scab.

There is also an importance that the piece is bed-like, as it is perhaps the symbol of the humanistic life-cycle, seeing as humans are usually conceived in, born on, spend a third of their lives in, procreate in and die on them. Therefore the work is in a way intimately visceral, yet in a perverse and perhaps widely social sense.

There are numerous cliched phrases attached to this somewhat simplistic form of interpretation, for example, as I have mentioned before, difficult relationships (as we seem to have here), can be described as 'no bed of roses', but what is being drawn to the viewer's attention is a definite beauty in the decay of things over time and I feel that this is what holds the fascination for the artist.

Tense

Anya Gallaccio, East Country Yard Show (1990)

The Grace Thalia also represented the quality of abundance, and the notion of impressive scale is also one which Gallaccio appears keen to question, much of her work consisting of large, geometric volumes of a material.

’Tense’ (1990) shown as part of the East Country Yard show, is typical of this technique. The piece consists of a 25' X 180* rectangle, in which are loosely scattered nearly 7,000 late Valencia oranges, weighing one ton in total. On a nearby wall hang silkscreened images of huge, ripened oranges on white wallpaper, which are arranged in a grid-like and Warhol fashion, in contrast to the randomness of the real oranges on the warehouse floor.

This piece is therefore strongly related to the idea of a work being site specific, the East Country Yard warehouse formerly being an old fruit storehouse. In this particular piece the viewer is presented with another duality, two differing versions of the same object. On the one hand, we have the highly polished silkscreened images, reminiscent of Andy Warhol (another exponent of the use of flowers), almost standing in testament to the other element of the real oranges themselves, rotting away on the warehouse floor. This seductiveness of the silkscreened image was shown to be only a temporary representation of a transient moment during the oranges’ lifespan. Hence, we are drawn to the debate as to the limitations of the painted or photographic image, the real oranges in fact bearing little or no relation to the images of them on the wallpaper. Yet any issue of narrative or subtext within the piece, or any exercise to subsequently uncover it is problematic, as the artist says herself:

“I just wanted to see what a ton of oranges would look like.”

Anya Gallaccio: Quoted by David Lillington in 'East Country Yard Show' TimeOut (1990)

Of course, this does not mean that speculation is removed from the viewer, it is merely a rationale for her initial method of producing the work.Photographic recording (indeed, recording of any kind) of transient works has been a perennial problem for artists, Gallaccio being no exception, yet this piece seems ultimately concerned with this fact alone, the rotting oranges giving a realistic, decaying version of the real thing (perversely, they are the real thing), against the printed images which prove to make a more lasting statement. I feel that an investigation into the particular use of the orange and the way in which the artist chooses to acknowledge its inherent qualities has to be made here. In a sense, any fruit becomes a metaphor for the human body (in particular the female body and its equation with fertility as with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden), the formalistic make-up of both of them being very similar. For example, both are mostly liquid, and both have a skin (which wrinkles with age). Also, there is a very definite discussion of color issues, particularly in relation to painting, making it somewhat traditional in approach. Painterly also in the sense that this somewhat fragmented color field is strictly bound by a very rigid geometric structure (an idea employed by Lynda Nead in relation to the female body throughout art history in her book ‘The Female Nude : Art, Obscenity and Sexuality’, Routledge, 1992), akin to the confines of the canvas. Yet the aspect of the work which I find most interesting and intriguing is its relationship to painting's color wheel.

Orange is produced by mixing together red and yellow, two primary colors, yet when the object of that color decays, it turns to green, another mixture of two primaries, yellow and blue. Therefore, a naturalistic questioning of the notions of color itself is perhaps being offered to the viewer.

Through this, it is also notable that an orange is one of the very few objects to be named after its own color, or vice versa. So by the very act of using oranges, we are presented with an interesting selection of dualities, questioning color and its painterly use, its relation to natural as opposed to photographic imagery, and even language itself.

The piece is also typical of the ordered, geometric frameworks which Gallaccio often imposes upon her work. The skin of the fruit encloses and contains a liquid, natural and bound chaos, just as the rigid rectangular frame employed to contain the oranges does the same. Their subsequent decay demonstrates that this natural chaos can be ordered by the Appollonian science of imposing mathematics, but not predictably controlled.

“Some people find it repulsive, but I think it’s quite beautiful and fascinating how things decay over time.”

Anya Gallaccio: Quoted by Ralph Rugoff in 'Dark Art' Vogue (September 1992)

Gallaccio's practice of questioning the natural decay of metaphoric materials presents us with interesting debates around the subjects of society, nature and the supposed ideas of the art world itself. This 'kinetic putrefaction* so often used in her work forces the viewer to re-evaluate their own social and bodily norms, and to also see the beauty in the decay of a material, rather than trying to employ the art world tradition of preserving a memory of an action, that action by its very nature, a transient one.

Sarah Lucas: Readymade Naughtiness

“My work is about one person doing what they can - it’s not corporate. I like the handmade aspect of the work. I’m not keen to refine it. I enjoy the crappy bits round the back. When something’s good enough, it’s perfect.”

Sarah Lucas: In conversation with Sarah Kent, 'Young British Artists 2' Saatchi Collection Exhibition Catalogue Essay (1993)

The themes and issues dealt with in Sarah Lucas' work perhaps relates her to the third and final Grace, Euphrosyne, she who rejoices the heart or ‘she who brings mirth’. The work is infused with this playful and almost aggressive sense of mirth, concerning itself with issues primarily around the subjects of gender and the rather grey and difficult area of socially reductive stereotyping (as was also discussed in Sam Taylor-Wood's work).

There is a definite ‘take me as you find me’ aesthetic, often simply presenting the viewer with an image or object, a perverse 'proof that it exists', a starting point or trigger for discussion. In doing this, it is a continuation and reflection of the infamous Duchampian readymade theory so prevalent in much of twentieth century art. Yet within the dangerous framework of this somewhat male dominated legacy, Lucas manages to subvert the notion of the readymade, nudging it slightly more towards a handmade aesthetic, which unlike the readymades of male artists such as Duchamp, Warhol or Koons, is incredibly unpolished and due to the nature in which it is made and by whom, undeniably female.

There is, in view of this, perhaps a simplistic link between Lucas' work and the somewhat infamous Duchampian urinal piece ‘Fountain’ of 1917 (in some sense ‘the’ readymade), conceptually concerned with the sub-surface sexuality of an everyday object and its transposition and existence within an artistic context.

Fountain

Marcel Duchamp (1917)

It is this realm in which I feel as if Sarah Lucas’ work operates. As I have mentioned before, there is a conscious and important 'handmade' aesthetic to the work (as opposed to the 'hands off approach of movements such as Conceptualism or Minimalism) which often leads to either simplistic dismissal of the work as ‘bad art’ or misinterpretation due to the, as she says 'crappy bits round the back'. It is, after somewhat of a legacy of completely machined and highly polished works, almost a return to allowing for a rough finish. What does ‘making’ a piece of work actually mean? Lucas appears keen to exploit and play upon this strong aspect of her work, being reminiscent of the so-called ‘slacker’ culture portrayed in American Douglas Coupland's literary work ‘Generation X’ (1991).

She produces images (and also sculptures) which at first appear to be promiscuously thrown together, yet, as in the Duchampian urinal piece, there always emerges a particularly considered element of a humorous and playful sexual discussion beneath its surface.

Of all the three artists which I have chosen to discuss, her work is probably most indebted to what one could generally term as Feminism. In this, I mean that it works within the feminine arena of debate established in the seventies, and uses the vocabulary and aesthetics of its subsequent conceptual empowerment of females.

Got a Salmon on (Prawn)

Sarah Lucas (1994)

Yet my purpose is not to try to define Feminism in all its different forms, as this is another, incredibly complex debate.

There is, however, a definite mocking of male sexuality in photographic works typical of Lucas’ approach, such as ‘Got a Salmon on (Prawn)’ (1994), and her images of fruity genitalia, as opposed to her use of women, which are either freakish, defiant, or consumed by a studied arrogance (in some sense they all seem to be under attack or exploited in some way). They appear to be sometimes autobiographical, often social, and always perverse. Hence, one could describe the work as operating in the social realm in an almost aggressively humorous manner.

“Carl Freedman : “Besides the aggression there’s also a lot of humor in the things you do, which acts as a counterweight and provides a balance.”

Sarah Lucas : “Yeah, well I like to have a laugh.”

Sarah Lucas: In conversation with Carl Freedman 'A Nod's As Good As A Wink' Frieze, No.17 (June / July / August 1994)

Lucas images of women are perhaps best explained by primarily looking at her series of Daily Sport works. Entitled ‘Seven Up’, ‘Sod You Gits’ and ‘Fat. Forty and Flabulous’ and all of 1990, they are basically concerned with what I might term the mass media (tabloid press in particular) and their ‘sizing’ and subsequent reduction of the female form. In presenting all three 'sizes' of women together (as happened with her shows at City Racing and the Saatchi Collection), the audience is presented with a perverse ‘spectrum’ of women, from ‘fat’ through to ‘normal’ and then to ‘small’.

Seven Up

Sarah Lucas (1990)

The works conjure up obvious and interesting correlations to the other group of media-exploited women, perhaps also associated with these notions of weight flux and self-image, the so-called 'supermodels', the ‘possessions’ of the fashion industry. It is particularly during adolescence that people tend to be weight and image obsessed, yet the presentation of what is ‘beauty’ and what definitely is not, would appear to be adolescently proliferated here by the media and tabloid press, perhaps to appeal to the moronic British male mind that Lucas (and also Taylor-Wood) is at odds with here. Yet in saying this, the Daily Sport is a perversely incredibly popular newspaper, and there is obviously a large and very real audience for this kind of reductive perversity, and Lucas draws our attention to this most unnerving of social elements. The works ‘Sod you Gits’ and ‘Fat, Forty and Flabulous’. depict the complete antithesis of the supermodels, thus posing the question of dualities (in relation to social criteria), are the supermodels freaks (to use the term of the Daily Sport) or are the women in the Daily Sport beautiful or vice versa? Who is deciding upon this criteria? It would appear that it is social conditioning itself which is being questioned here.

Fat, Forty and Flabulous

Sarah Lucas (1990)

Photocopy on paper, 85 ¾ × 124 ¼ in. (Sadie Coles HQ, London)

Sod You Gits

Sarah Lucas (1991)

I do however feel that the works hold more than the simplistic view of looking at how 'men use women', yet through their very aesthetic make-up (photocopies pasted onto canvas), they are instantly corollary to the traditional idea of the framed, painted female from art history. One is reminded of plump figures from a Rubens painting, or of Brigid Polk at the height of her weight problems in Warhol's Chelsea Girls (Warhol, 1966) (indeed,Warhol's newspaper paintings must hold some close reference here). Lucas' works are somehow far more debased than that. They're not painted, purely pasted up and presented for discussion, and I feel that because it is the artistic 'action' which seems simple, the audience is almost invited to take the work on this perhaps basic and primary level.

Lucas holds up the Daily Sport as an example upon which to base a critique concerned with the stereotypical notions of beauty. It is not perhaps misogyny, as the Daily Sport are also interested in images of men or anything else which could be considered to be ‘freakish’. It is barely pornography(the telephone sex lines with the theme of 'woman as commodity' being the only true reference for this). Lucas brings to our attention the methodology by which the tabloid press proliferate one of the basic assumptions of the male-dominated media society, that there is no beauty (an art fundamental) in images such as these, yet here in an artistic context, as before with Duchamp, this is re-evaluated, and we can see that the subject matter of these images of hers operate on a similar moralistic high ground as that of the supermodels of the fashion industry's catwalks. They are at odds, but at different ends of the same spectrum, and therefore inextricably linked.

This method of interpretation leads to an investigation and appraisal of her role as a female artist. A constantly moving target (like Sam Taylor-Wood), the handmade quality of her work going against the supposed ‘vogue’ of the eighties art boom, where polished, machine finished objects by artists such as Jeff Koons, Ashley Bickerton and Haim Steinbach seemed very much in favor with collectors, gallerists and curators around the world.

‘Got a Salmon on (Prawn)’ (1994), shown as part of Anthony D’Offay's new gallery project, depicts her close relationship with artists such as Koons, but the subsequent rejection of the eighties passion for polished, consumable objects. It consists of nine cibachrome photographs, mounted upon aluminum, showing the torso of a naked male, a can of lager replacing his penis, and a storyboard-esque progression of him subsequently masturbating with it. This substitution of male genitalia is an ongoing concern of Lucas' and a relation back to her previous use of bananas and apples in a similar way.

In these pieces, there is a definite awareness of the female's contrived or supposed fascination with male genitalia and vice versa (yet another social stereotype of both sexes), and particularly in relation to her own practice as an artist. Yet the subject of male genitalia is perhaps still very much a taboo area of art (possibly also with the male rectum). Despite being drawn attention to during the late eighties by such artists as Robert Mapplethorpe,

It is still apparent that (even in the age where we supposedly have seen ‘everything’) it is still strange to see the male organ exposed as in this case. It goes against the complete tradition of art history in that it refuses to 'cover up what has traditionally been viewed as a secret, discreet but also powerful symbol of male sexuality. In this sense, it also exposes male genitalia as incredibly vulnerable symbols of a supposed and often fantastical 'prowess'.

“A dick with two balls is a really convenient object. You can make it and it’s already whole. It can already stand up and do all those things that you’d expect any sculpture to do. In that way it’s really handy, I mean I could start thinking about making vulvas but then I’d have to start thinking about where the edges are going to be.”

Sarah Lucas: In conversation with Carl Freedman 'A Nod's As Good As A Wink' Frieze, No.17 (June / July / August 1994)

Left: Achetez des Pommes (Anonymous nineteenth-century photograph, courtesy of Linda Nochlin)

Right: Linda Nochlin, Achetez des Bananes

This substitution of sexuality through the use of foodstuffs is not new to art history. Reminiscent of the numerous Gauguin paintings of young girls with bowls of fruit instead of breasts, or Dutch Vanitas painting, I feel that Lucas’ use of this style has perhaps more in common with the work of feminist writer Linda Nochlin than Paul Gauguin. In her photopiece ‘Achetez des Bananes’ (1989) a Feminist re-evaluation of art history is taking place (the work is made in conscious reference to another piece from the nineteenth century by an anonymous artist entitled ‘Achetez des Pommes’), the male's libido being reduced down to a similar shaped fruit.

Yet to return to ‘Got a Salmon on (Prawn)’, the piece reads like a cinematic storyboard, a frame by frame recording of some form of perverse autoeroticism. Obviously the male (notably devoid of personality in image but conceptually abundant in it) is masturbating, therefore the link between the phallic erection and lager drinking is made very simplistic. In a similar way to the targeting of the 'laddish boy racer' in Taylor-Wood's ‘Spanker’s Hill’, Lucas is also using stereotypical ideas of the British 'lad' as a target perhaps at which to launch a social critique, directing it at what could be seen as the prospective audience of the Daily Sport (and also using the same vocabulary to achieve it). Yet how effective is this? Art's social appeal is fairly limited, and for this work to have any great effect upon the 'lads' in question would therefore require a remarkable set of circumstances.

“The Daily Sport is a journal with its finger on another sort of pulse.. . this is the pulse of the moronic British male for whom blood is something you dilute with lager and then pump into your penis by looking at photographs of stunners with their tops off.”

Waldemar Januszczak: 'Blood and Thunder' The Guardian (8th February 1994)

The somewhat simplistic reading of a direct attack on this social group (perhaps a reversal of the assumed boy racers’ attitudes to women), a sort of ‘lager drinking is for wankers’ interpretation is however only half the issue here. Of course the piece is incredibly unsubtle, but then isn't the image of the penis being the hidden focal point of the work (as with art history's attempts to 'subtilize' phallic references) also particularly conspicuous when pumped with blood and lager?

Januszczak's reference to blood may also have a more subtle and significant overtone. There are nine photographs, which equates with the nine pints of blood in the human body, and the subject of the work (the penis), requires the transfer of blood into it for it to function sexually. Thus, if the can of lager is ‘in the way’ (i.e. causing 'Brewer's Droop'), the male is then rendered completely impotent and it is this which is being analyzed in the work. Why and how does this physical state occur? Lucas renders the male in the piece impotent (again an aggressive yet playful methodology is at work here, behind which there is a somewhat serious Feminist act) in a humorous with the male actually ejaculating, as opposed to Lorena Bobbitt, but still manages to contain a serious critique of social norms and human behavior by using a reversal of attitudes (of the eighties as a reflection of the nineties?) through a socio-visceral vocabulary. It is also notable that in relation to the 'nineties' the work also reflects the advertising industry, who rediscovered the male body as a targetable market, and were keen to exploit its subsequent aesthetic appeal for both male and female products.

1-123-123-12-12

Sarah Lucas (1991)

Boots with razor blades, 63/4 × 4 × 107/8 in. each. (Sadie Coles HQ, London)

The final piece of Sarah Lucas' which I wish to discuss is the sculptural work entitled Size Seven Boots with Razor Blades (1991). Again, there is a very real danger of too simplistic a reading, causing assumptive links with only generalized subjects. Here she uses the same attire of the 'boot boy' featured and perhaps attacked in ‘Got a Salmon on (Prawn)’ except this time, these are her own boots, tailored into serious bother boots.

Described by Sarah Kent as 'seriously defensive footwear’ (‘Young British Artists 2’ Saatchi Collection Exhibition Catalogue Essay) perhaps against the supposed male hegemony of the art world, Lucas uses the debris of the everyday studio experience, her old work shoes, to present her own somewhat defiant contribution to art history.

Shoes

Vincent van Gogh (September-November 1886)

There is a legacy of depictions of artists' shoes (Van Gogh being a memorable example of this), and is corrolary to the recent exhibition at the Fundacio Pilar i Joan Miro in Mallorca entitled ‘Used shoes and artists’ studios’ in which many artists (notably predominantly male), exhibited old shoes as some kind of key or signifier to the mystique of artistic practice. Santiago B. Olmo says of these shoes, that they are clues to the landscape of the studio, the ways in which the artist works and moves (Quoted by Deirdre Stein in ‘Shoeshines’ Art News, September 1994). Therefore, Lucas is playing with the most unlikely of signifiers to launch a playful kick into the sides of the male enclaves of art history.

In conclusion, Sarah Lucas’ work operates through and on a very social level and presents the viewer with images as starting points for critiques, not only of male hegemony, but also of the moronic individual (both male and female) encountered on a daily basis. She confronts this with an aesthetic and conceptual arrogance, that is both as studied as it is playful.

Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: Conclusion

Based around the somewhat simplistic premise of marrying together two seemingly disparate historical elements, in using the Three Graces as my subject matter, I still feel as if I am following in a particularly historical tradition within the art world.

How is it possible to relate these artists to each other? What are the similarities or common themes? To begin with, there are the very obvious ones, which I used as criteria for originally selecting three contemporary artists, such as they are all young British females who all studied at Goldsmiths' College. Yet I feel that perhaps what seems to be the most apparent and interesting link between all of their work is their collective relationship with the Abstract Expressionist era of the 1940’s and 1950’s.

The New York school as it was called, was almost exclusively a boys only club, with women being almost completely excluded from any kind of ‘history’ of the period. If they were included, as was rarely the case, they were almost seen as 'token' artists, subordinate to the 'greatness' of the males' work. In re-analyzing this period, what seems to be under scrutiny is the idea that there are multiple 'histories' made within each period or movement, which obviously are bound to exclude certain people (Tony Smith and Minimalism being a memorable example of this). Yet to exclude a whole sex seems to be almost unacceptable in this age of 'Political Correctness', perhaps this is the reason or rationale behind my linking of their work with this period.

For Sam Taylor-Wood, there is an obvious correlation to Hans Namuth's fictions of those artists in their studios (the imagery of Pollock being the most infamous of these), particularly in such pieces as ‘Fuck Suck Spank Wank’ (1993) and ‘Gestures towards Action Painting’ (1992). It is the notion of the specific documentation of a period of history and the way in which there are often multiple histories due to individuals being left out which being re-evaluated and assessed in a kind of 'correcting the mistakes of the past' gesture.

Similarly with Anya Gallaccio's practice (concerned very much with these ery issues of documentation), the link to this period is also often direct. ‘Red on Green’ (1992) as I have already discussed, is titled from a Rothko painting, and the very fact that the majority of her works are floor-based sculptural installations, and geometrically structured, akin to a canvas, also reminds one of the experimental painting techniques of the Abstract Expressionism period. With Sarah Lucas, the link is perhaps a little more ambiguous. There is some relation in the actual making process and final product in that they both display an aesthetic 'crudity' (I use the term at my own risk) or desire to push the actual fabrication process of the work rather than focus upon particular end results, this paradoxically in opposition to the Greenbergian methodology. This suggested that the art object be autonomous and 'pure', and be concerned with such aspects as the interaction of the viewer with the surface of the object. This had the effect however of formulating a rigid process of making, and it is perhaps true to suggest that prescription is always undermined. Yet why is there this link between the female artists and the New York School? I feel that the most important issue here is gender.

Abstract Expressionism, as I have already said, was a predominantly male engineered movement, with very few women being included into a sense of history of the period (Lee Krasner perhaps being the exception), so for these contemporary artists to draw upon this period, it is possible to re-evaluate the history of, or even ‘feminize’ the era, in a kind of metaphorical redressing of power. There is obviously a railing against some form of art history, and this period in particular, being male dominated, seem ripe and apt for their exploitation. That is not to suggest that these artists are purely concerned with this issue in their work, they draw on the period to make sense of the processes and methods they employ in attempting to bring our attention to the notion that Abstract Expressionism can be more than just a male enclave. In regard to this, it was also perhaps the last definable 'boundary' in terms of an art movement, as the period of Modernism following it in the sixties was very much concerned with the breakdown of fundamental terms of art ('movement', an obvious example, but also the boundaries between such practices as ‘artist’ and 'writer' became increasingly blurred). In this sense, the terms 'artist* and 'artwork* are perhaps what one could imagine to be the traditional ones (i.e. the painter working in the garret).

Sarah Lucas: Bucket Of Tea (1994)

24 June 1994 – 7 September 1994 (White Cube, Duke Street, London)

White Cube presented Bucket of Tea (1994) by Sarah Lucas, a mobile suspended from the ceiling by a network of wires and rods, that featured four large, colour-photocopied self-portraits backed by mirrored styrene. The artist had made cut outs from a series of self-portrait photographs taken with a wide-angle lens, whose distortion served to increase the in-your-face attitude of the portraits.

These pictures present Lucas languishing with laid-back defiance in an armchair, wearing jeans, an old leather jacket and worker’s boots; she sits with legs apart and boots dramatically enlarged, pushed up into the foreground. The movement of the floating images conveyed a listless mood with the artist suspended in an uncertain equilibrium, this fragile condition seeming to undermine the tough self-confidence of the portraits.

This notion of process and materials is also a strong bond between the contemporary artists. For example, their particularly problematic relation to the photographic recording of their work. I have already discussed Gallaccio's somewhat difficult relation to photography, and Sam Taylor-Wood and Sarah Lucas both seem particularly interested in it as a way in which to record aPerversely staged 'scene' or performance (‘Slut’ and ‘Bucket of Tea’ both of 1994 are obvious examples). This notion of ‘construction’ of an image, particularly in relation to photographic 'truth' through a laborious, chorish and complex process leads to the assumption that these are traditionally domesticated activities. Yet their work is far more studied than this. It is debased as opposed to polished domesticity (perhaps an odd sense of their femininity), hinting at an aesthetic, sexual and moral decay of society as a whole rather than just the art world itself.

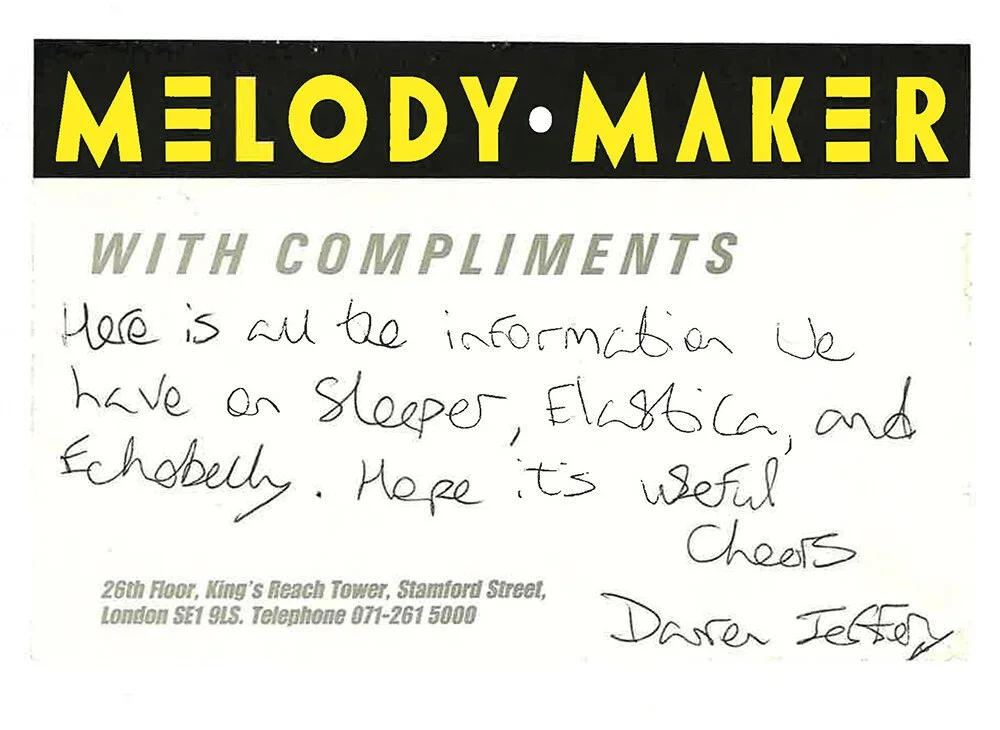

The ephemeral nature of all of their works (even though photographic recording fairly permanent) bares close relation to the wider sphere of the mass media, and the transitory nature of 'trends' within so many aspects of the commercial public sphere. In relation back to the ideas of Modernism, it was the very invasion of such advertising material which was a factor in artists rejecting the ideals of the autonomous art object in favor of embracing the culture of which they were a part. This was particularly apparent in the case of 1970's Feminism. Contemporary music being a primary exponent of the 'trend' idea, I therefore somewhat speculatively feel as though there is perhaps another 'musical' version of the Three Graces, which might correlate with my 'artistic' version of the same subject.

Recent music press attention in Britain has focused upon the English proto punk pop bands Sleeper, Elastica and Echobelly, who are all fronted by young female singers (Louise Wener, Justine Frischmann and Sonya Aurora Madan respectively) and their particular breed of music (branded the ‘New Wave of New Wave’ by the music press) superficially appears to be very much akin to the practice of their possibly corrollary artistic counterparts. For example, Louise Wener's Sleeper, in their song entitled ‘Lady love your countryside’ are dealing with direct issues of a debased sexuality, arrogance, boredom and many others also dealt with by Sam Taylor-Wood. The song even contains the lyric “And we could spend our lives puking in Belsize Park”. This has an almost direct relation to a projected piece of Taylor-Wood’s, whereby a model is seen to be crawling around on all fours and vomiting in South London's Kennington Park. They both appear to revel in their own joy of sexuality, and are particularly concerned with their relationship to the male libido (Sleeper's ‘Swallow’ being a good example of this).

Similarly with Aurora Madan and Gallaccio, the signifiers of decay, oppression, sexuality and language (indeed, difference in general) are both studiously treated with an inquisitive as well as conceptual process of indifference, determination and above all, subtlety. As regards difference,I feel that they perhaps are both particularly aware of their role as female 'makers', yet in the sense that they do not seem concerned with the debates of Political Correctness. Gallaccio is perhaps keen to imply her difference in terms of gender and context in relation to what could be termed the 'last major art movement', whereas Aurora Madan is particularly railing against her experiences (also of difference and possibly more to do with the P.C. debate) of being from an Asian immigrant family and having to 'deal' with the previously discussed 'Moronic British male'.

However, Frischmann's relation to Lucas is perhaps more aesthetic than conceptual, the links between their practices very much concerned with the 'Big Boots and No Knickers' ideology of recent girl proto-punk practice. Both appear particularly keen to present a particular 'aesthetic', which is, asI have discussed before in relation to Lucas' work, more playful and humorous than it is aggressive.

Although not really related to the notion of the Classical Three Graces, the musical version can still be seen as a corollary to them, yet in the sense of a particularly modern phenomenon which has its roots perhaps planted tenuously in the ancient past. As for other versions, such as my original premise of defining a so-called ‘cinematic’ Three Graces, there seems to be little material to bind this idea together. Due to the nature of cinema, particular actors and actresses are inconsistent as 'makers' due to their constantly changing personae. There is some relation to the films of Winona Ryder, Drew Barrymore and other ‘Generation X’ actresses (‘Reality Bites’ or 'Singles’ being fine examples of this phenomenon of the contemporary lifestyle film), yet as there is a constant flux in character (yet in a different sense to Taylor-Wood) the relationships become about specific events rather than an overall conceptualized sense of 'whole'.

I still feel very conscious to stress that these interpretations of the possible combinations of the Three Graces (and its use as a metaphor for re-analyzing some aspects of contemporary practice) is very much my own subjective and speculative view. It is purely employing the methodology of re-analyzing elements from contemporary practice through an ancient vocabulary. Questioning the present in terms of the past.

The existing notion of the Three Graces is therefore somewhat of a formidable historical force, having been upheld for so long. The contemporary artists are very much concerned with their own relations to ‘permanence’ (indeed, it has always been a fundamental of artistic practice) and it would appear that the notion of the Three Graces brings into question the historical existence of artworks. Why is there a particular need to uphold such icons for so long? I feel that as Classicism was particularly concerned with objects of beauty, this idea has lasted, as we still have a stereotypical assumption that the art object is 'a thing of beauty'. As the Three Graces can be seen as almost a personification of this idea (it is a social definition of artistic beauty), there will always be a place for the work in the world's major art collections. I also feel that the work espouses other stereotypical notions of what art should be', in that the subject is female, it is made of a traditional sculptural substance (marble) and it also depicts characters from mythology there is a legacy in the subject matter which extends centuries before Canova's interpretation.

Therefore, by proposing a corollary set of ‘contemporary’ Three Graces, I am helping to perpetuate the myth of the work. As a personification of the supposed ideals of artistic beauty, the Three Graces proves itself to be a historical monument, and a challenge to the artistic notions of permanence, which, as I have discussed during the course of this work, is as relevant in contemporary practice as it was at the time of Canova's interpretation.

Sarah Kent Conversation Transcript

Serpentine Gallery, 7th August 1994

Piss Flowers

Helen Chadwick (1991-1992)

Matthew Shadbolt: You talk about Helen Chadwick being like the forerunner for British women artists. I'd like to ask you, how far do you think that influence goes, because obviously there's a lot of references to the younger generation's work, certainly in the works in this show. like the chocolate and the flowers with Anya Gallaccio's work, and..

Sarah Kent: But Helen Chadwick's been using flowers for ages.

M.S.: But also Sarah Lucas's work with the Xerox pieces and the penis and vagina imagery, and Georgina Starr's crying piece links with Chadwick's weeping photomat works. Do you think that Helen Chadwick is like a ‘spiritual ancestor’ to a lot of these younger artists?

S.K.: Yes, yes I think so, but I don't know how overt it would be...

M.S.: There seems to be elements in Helen Chadwick's work of all their work. How far do you think the influence goes?

S.K.: You'd have to ask them, and also it's often very difficult to tie in influences because people are often unaware of them, I don't think there are obvious ones, I mean when Anya Gallaccio uses flowers I don't think she's consciously thinking of Helen Chadwick. Yet the relationship is very close, there's no doubt about it. Also, the way that a lot of the younger artists use the installation rather than making objects, which goes back to that idea that you don't make something fixed, you make something temporary. Anya Gallaccio's flowers are always going to die.

MS: But that process still relates to Chadwick’s ‘Carcass’ that she did at the ICA.

S.K.: Yes.

Effluvia

Helen Chadwick (1994)

M.S.: Everything being enclosed and decaying, and with Chadwick’s chocolate piece, that actual formal volume of it, is something that Gallaccio uses.

S.K.: Yes, you mean with the oranges, a ton of oranges wasn't it.

M.S.: It seems like Chadwick is like the kingpin linking certainly at least five young British women artists.

S.K.: Yes, but I don't think it's that specific, it's more about using a certain set of ideas and that they've infiltrated down.

M.S.: You can see Helen Chadwick as the sort of ‘mother’ figure in a family tree. with all these strands coming off... there are common themes.

S.K.: Yes, I agree.

Correspondence

Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: A Contemporary Three Graces

Kingston University Main Lecture Hall (4th November 1994)